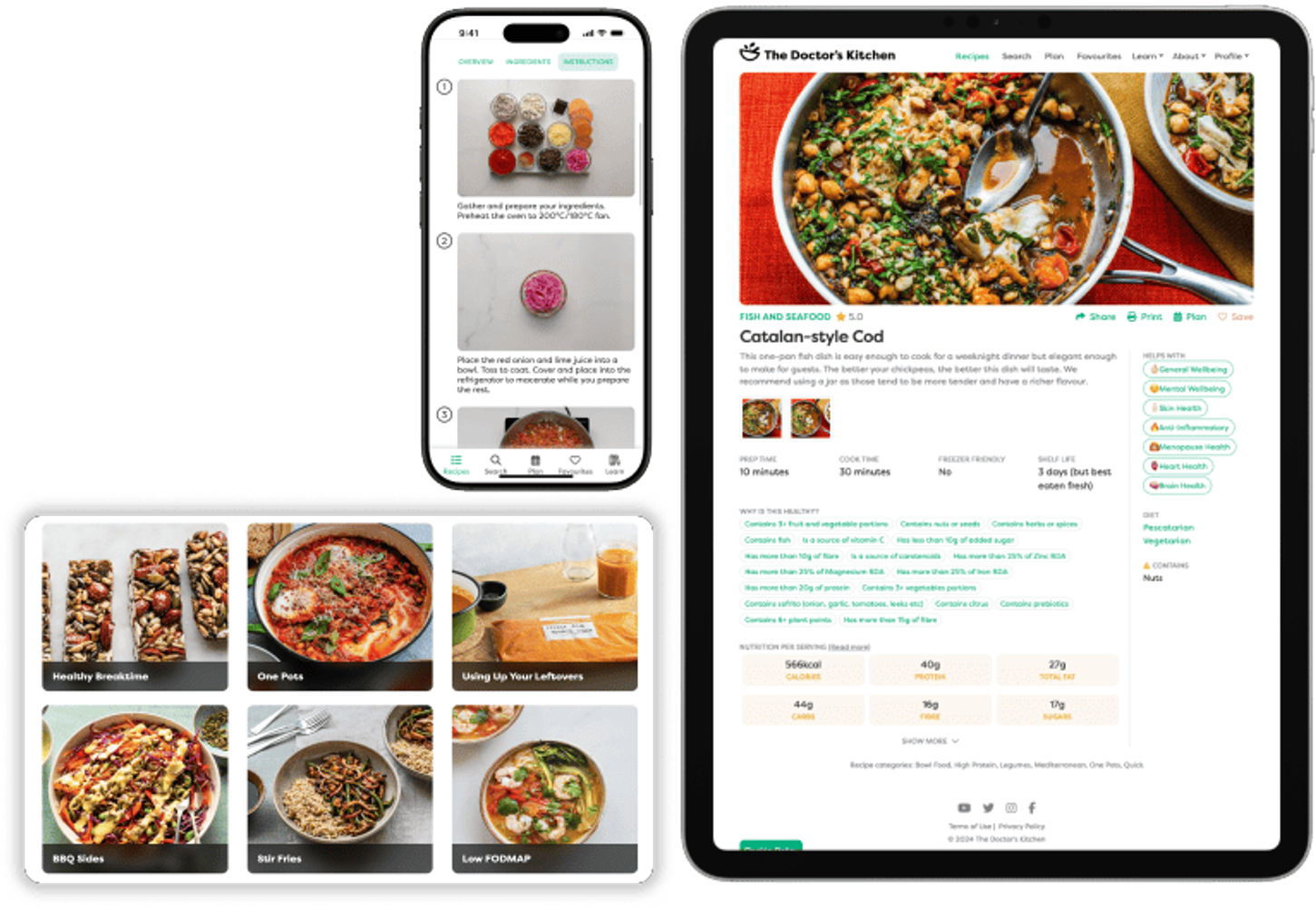

Dr Rupy: I am sitting in front of all of you thirty years into a stage four ovarian cancer diagnosis where I should have been dead multiple times over. And I'm still dealing with a managed disease process. I am not in remission. That's not the goal. I'm not, that is not the focus. I want patients to thrive and I live an incredibly rich and full life with cancer and I want other people to find that hope that they can do the same. Welcome to The Doctor's Kitchen podcast. The show about food, lifestyle, medicine and how to improve your health today. I'm Dr Rupy, your host. I'm a medical doctor, I study nutrition and I'm a firm believer in the power of food and lifestyle as medicine. Join me and my expert guests where we discuss the multiple determinants of what allows you to lead your best life. Today's episode contains some pretty stark descriptions of how many environmental pollutants we are exposed to, which is scary and could be triggering for a number of people. Dr Nasha Winters, who has suffered with cancer herself, does not shy away from the realities of our toxic exposures and dealing with cravings for addictive foods. So, if you feel that you may be triggered by these descriptions, then I reckon this is probably not the podcast to listen to. Sakina, who's one of the researchers at The Doctor's Kitchen, is also interviewing Dr Nasha on the podcast, and I think you'll agree with me that even as a podcasting novice, she navigated this difficult and complicated topic with grace. And listening back to this conversation, I was super, super impressed. Part of the reason why we wanted to release this episode, despite it being slightly out of the norm of our typical conversations, is because we need to build mental resilience to these realities. Unfortunately, we do have a toxic environment. And in fact, in the UK in December 2020, Southwark Coroner's Court found that air pollution made a material contribution to the death of nine-year-old Ella Kissi-Debrah in 2013, after two years of severe asthma attacks and cardiac arrests that led to multiple hospital visits. Our environment is having an impact on our health, whether we would like to appreciate that or not. And I will be personally diving into these topics a lot more. So, I would keep an open mind for today's podcast. As a survivor of cancer herself, Dr Nasha is super passionate about creating a new standard of care for cancer. And I think it takes some radical and brave thinking to even conjure this. It may seem completely unthinkable and naive to imagine a cancer centre that incorporates a blend of naturopathic, conventional oncology, environmental medicine, mind-body treatments and nutritional interventions. But I think we need some radical thinking injected into medicine, if I'm honest. I mean, if we can aspire to put people on the moon and become an interplanetary species, then I think we should allow ourselves to dream bigger when it comes to tackling the most deadly and emotive of conditions on planet Earth: cancer. Dr Nasha is a healthcare authority and bestselling author in integrative cancer care and research. She consults with physicians around the world, educated hundreds of professionals in the clinical use of mistletoe, something that we didn't get a chance to talk about today. Dr Winters is also currently focused on opening a comprehensive metabolic oncology hospital and research institute in the US, which will provide the best that standard of care has to offer alongside the most advanced integrative therapies. Remember, you can watch this episode on YouTube as well as listen to the podcast and download The Doctor's Kitchen app for free to get access to all of our recipes with specific suggestions tailored to your health needs. Android users, I'm working on an Android version very, very hard. And in the meantime, you can check out the Eat, Listen, Read newsletter. Every single week, I send you a recipe to eat, something to listen to, something to read, and a joke at the end of the email just to put some sparkle in your day. For now, on to the podcast with Sakina and Dr Nasha. Enjoy. Before we get started, here is a quick word from the people who make this podcast possible.

Sakina: So I heard that you've been working on a hospital, opening a hospital. Yeah. Um, metabolic oncology hospital. Can you tell us more about that?

Dr Nasha: Sure. Over thirty years ago, I faced my own mortality right in my face with a terminal cancer diagnosis. And in the ensuing years, especially the first five or ten years, I had to literally piecemeal together from all over the world, from everything I could find, because remember, you guys, first of all, in 1991, none of you were even thought of yet in this room. There was definitely no Dr Google. There was something called the Dewey Decimal System and very antiquated library data that was out there. So I had to piecemeal together an approach that kept me alive and to learn everything I could about oncology. That showed me early on that what it's going to take to survive the unsurvivable is absolutely not being offered in standard of care today. And that the folks who are able to have the resources, both mentally, but also financially, to piecemeal those together, leaves most of us without being able to approach this care for ourselves. And so about twenty-eight years ago, I started having a very specific vision of an entire institute on under one roof that brings in the best of standard of care, all of the diagnostics, the imaging. Today, I mean, my gosh, thirty years ago, we didn't know about tumour assays and liquid blood biopsies and epigenetics, but all of those pieces will be screened in every patient coming in, along with their regular labs, along with their functional labs, along with a very intensive, I mean, our current intake form is fifty-four pages for crying out loud. We want to know every single thing about the patient. And then we want to be able to match the best therapies at the best time, at the best dosing with that patient. And that might include surgery or metronomic chemotherapy or high-dose vitamin C or mistletoe or any combination of those pieces. And done in an environment that is actually conducive to healing. Because most of us go to hospitals and many centres that are absolutely as toxic as the environment that made these patients sick to begin with. So there's no accounting for, you know, just the the physical environment. The light is terrible. You're so far from nature. It's so sterile. It's so unwelcoming. It's so not healing. It actually can be very distressful to people's nervous system. Then you have all the things of the toxic materials that that building was built from. And then, do we even want to start about the toxic food that they serve you in these environments that they are bringing into the most vulnerable populations that need deep nourishment and yet it's anything but. And so I had this vision that has just built over thirty years and is coming closer and closer to fruition. It's a hospital on a massive acreage of farming. It's a huge regenerative organic agricultural project that happens to have one of the crops as a hospital. And so it is the metabolic terrain Institute of Health and it focuses on all the aspects of the, of the body from mind, body and spirit, but it also very much does so through the best of science, the best of what we have to offer in analysing that body to our the best of our abilities. And then to, you know, top it off, it's in an incredible environment that is seamless with nature, that is absolutely every single detail has been thought of from being completely off grid to the organic food that's that's grown and served on the property to the patients in the fields with the farmers and the the doctors in the fields with the patients and everyone together in the kitchen preparing these foods. On the campus, we'll also have an event centre so we can actually house events like this in environments that don't make us sick. Because by the end of today, I won't feel very well. With all this terrible lighting and who knows what the quality of water or any things we might be eating here. I want to have an environment where people come to learn but also to thrive while they're learning or thrive while they're healing. And then there'll be things like green retail and an equine centre and a wellness centre and farm-to-table restaurants and basically a community that shows people how to live healthy on an unhealthy planet. So it really does, we call our concept from the soil to the soul and everything in between. That's what we're focusing on in the metabolic train Institute of Health. And the first one is poised to be built in Arizona in the United States. And we hope that it is a a beginning of little campuses like this all over the world.

Sakina: That's absolutely amazing. I've never heard of anything like that. And it's funny you mentioned about this conference. I was thinking about that. People are flying from all over the world. They're jet-lagged, they're tired. It's quite brain-draining to be having all these conversations. But we are still in this environment where we don't have access to great food and snacks and hydration. And then also, as you were saying, the lightning, the lack of outdoor spaces in an environment where we should be thriving and sharing ideas and talking. So it's really, it's really interesting that you're focusing on that. I'm really looking forward to see what what's going to happen with this space. Um, so you talk about many different fields. So I'm guessing it's going to be quite a multidisciplinary team working in there. So could you tell us more about the members of the team, what type of doctors are going to be there?

Dr Nasha: Well, currently I'm training, we're creating our network. We're creating our web that goes around the world. So we have, this is, gosh, this is spring of, you know, spring, summer of 2022. And at current date, we have eighty-eight physicians who've come through our program, everything from naturopathic doctors to physician's assistants to GPs to conventional oncologists. It's a very eclectic and varied blend. And everyone comes with a variety of expertise and backgrounds. Almost all of us are in it because we've been touched by cancer very personally, either directly to ourselves or to someone that we very much love, or we recognise that because of the statistics that one in two men and one in 2.4 women will meet this diagnosis in their lifetime, we need to become a lot more prepared as clinicians to support those patients on this journey, because we're not doing a heck of a good job as is. So we have a growing network there. We have a new cohort starting in September. We're expecting another, you know, fifty, sixty so doctors in that program from all over the world. And we need more because we have about a thousand inquiries a month coming in from all over the world looking for doctors who've been trained in this methodology to apply this tool in their own practices. So patients are demanding this. The doctors aren't, but they're coming, they're starting to learn that they need to know how to do this. We also train patient advocates. And this is really exciting to me because I'm, like that's where it started for me. I had to advocate for myself as a patient. And it inspired me to become a doctor, but it's the same way that nothing would have happened had I, the patient, not made it make it happen. And so we have almost two hundred in training right now with another cohort starting in the fall with probably, we'll probably matriculate a hundred every two, twice a year. Both programs, we always do a September and a February for the physicians and a October and March for the patient advocates. So right now we've created or are creating this global network. Those folks are out there to help share this narrative of what needs to happen. As I'd said earlier before we started talking about the hospital, I want to make this accessible to everybody. That is our huge goal here. So the hospital itself is nonprofit. It will be cash only and there will be a sliding scale for people with means. We will also have grants. We'll have philanthropic donations so people will be able to apply for scholarships and it's a research institute as well. So we will have research grants so a lot of people can come and take part in clinical trials that are there. So our expectation is people will come and spend a few weeks having thorough workups and getting these various therapies applied to them and then they can take them home and continue them under the care of someone who's been trained in our network so that they can maintain a seamless integration of this and ongoing support of this in their lives. So that's happening. And then simultaneously, when I hear I gripe, I hear people gripe about integrative oncology, they usually say, well, there's just no research or they're charlatans and trying to take your money. Well, I mean, that's why we're creating this nonprofit model so that we can show that this really is accessible for everybody and it's not about making money, it's about helping people. And then the other side is the research, we're collecting millions of data points in a very, very robust data platform that we're building out right now as well, that will be launched to help doctors see all of that volumes of data in real time because it takes me an average of seven hours per patient to prepare just to get ready to sit down with the patient and tell them what I'm seeing about their case. And so that's not sustainable and that's not scalable and that's not realistic. And so our data platform should take that down to under an hour and help the doctors really focus their clinical decision making. Because my biggest pet peeve is that patients come to me and they've spent all of their resources doing all the wrong things in all the wrong places at all the wrong times, from standard of care to alternative care and everything in between. We start from the beginning to really know the patient and to know precisely where they need to start and can monitor every step of the way to help them pivot as needed to what's going to help them manage this chronic disease process. And if they happen to go into no evidence of disease, fantastic, that's a great side effect, but it's not our end all be all. Because I'm sitting in front of all of you thirty years into a stage four ovarian cancer diagnosis where I should have been dead multiple times over. And I'm still dealing with a managed disease process. I am not in remission. That's not the goal. I'm not, that is not the focus. I want patients to thrive and I live an incredibly rich and full life with cancer and I want other people to find that hope that they can do the same.

Sakina: Wow. You've mentioned so many interesting things there. But you talked about the limitations a bit of our current approach to cancer. So I would like to go into a bit more into that and maybe you could walk us through what a consultation would look like in that hospital. So what would be the experience for a patient coming in with their diagnosis and yeah, what would happen and how it would go. But the limitation first of how it's going right now.

Dr Nasha: Sure. So today in standard of care oncology, we, we're trying to give it lip service that we're doing precision medicine. So, you know, a patient, what happens typically, they they get diagnosed based on maybe symptoms that get them into the doctor or something that's found on a routine exam or accidentally on their own. And then they typically have blood tests. Most often they end up with a biopsy. And at that point, the biopsy tells them basically what tissue is affected. Is this pancreatic cancer? Is this breast cancer? Is this prostate cancer? And then from that information, we typically do imaging to see if it's left the building, if it's still in in in situ or in in its spot of origin or if it's encroached into the circulation and into other parts of the body. And so then we create staging. And then based on that, we typically design a standard of care treatment approach, which almost always includes some form of surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, targeted therapies, hormone blockade therapies, and even when the targeted therapy, that includes the immune therapies. That's a targeted therapy as well. So that's what's offered and those are really, they're powerful ways. Those are all, the goal of those therapies is to cytotoxically reduce. And simply what that means is it says, make the tumour burden smaller in whatever form is possible, with whatever tool is possible. That's their goal. The whole focus of standard of care oncology is based on the tumour and the tumour cell and the tumour pathways. That's what we've been focusing on for seventy-five years and it's, it's kind of a failing process, right? We are, I mean, my gosh, when I told you the statistics of men and women expecting to be diagnosed with cancer, why are we not putting research into the why? And then when the World Health Organization shows that by 2030, we will double our cancer population worldwide. That's pretty horrific to consider that. And that in the last nineteen years, we've had, seventeen years, we've had about ninety-six new drugs to the market for for, a study was done on these ninety-six new drugs to the market that overall, the best they can offer patients when you put them all together and you look at the statistic, they offer you at best 2.4 months of overall survival. And that doesn't even talk about the quality of life of those patients. We can do better. We have to do better. And so now we're starting to run all these amazing genomic testing on patients and molecular profiles and everyone gets all excited about that. And they're like, oh, you've got a RAS mutation or a BRAF mutation or a MEK mutation. And we keep going after the single target and single treatment approach, which is failing us. And then we also still use an approach called the maximum tolerated dose approach, which is pretty much let's napalm the field and see what's left and hope the patient survives it, right? Most people don't die of the cancer itself. They die of thrombotic events, meaning a blood clot because cancer changes the coagulation in the body. They die of cachexia, which is a non-caloric related deficiency, metabolic shift in their body that makes them basically starve to death in order to feed the tumour. And then just the side effects of treatment. Those are the primary causes of death in somebody dealing with this. Those three things can be very well managed with the integrative model. So it's not even about saying standard of care is crap. It's about we can certainly help it do better. And we can also, when we bring in other tools, we can help standard of care, you don't have to use as much. So instead of using maximum tolerated dose, we can go into what's known as the adaptive theory. So we push back the burden just enough to give the body a running start. Okay? Like that is huge. It's like you push back the tumour burden just a little bit so that the rest of the body can step in and do its job that it was absolutely perfectly designed to do. And there's a lot of different tools in the integrative model that can help do just that, which also enhance the standard of care and protect the healthy cells while driving the standard of care more deeply into the cancer cells or the cancer, the tumour. So that's like the the deficits of standard of care. And it drives me nuts that we aren't creating this bridge because even in the alternative world, this is just as problematic because in the alternative world, they're like, you never need chemo or radiation or surgery or targeted therapies and they're the devil and, you know, don't even consider that. That is just as dangerous as standard of care saying, don't even think about taking an herb or fasting with your chemo or considering mistletoe therapy or, you know, any like cryotherapy or sauna therapy. Those are are wacko and charlatan, you know, approaches to this. Both are wrong. Both are absolutely wrong. And so my entire life, thirty years has been about building this bridge. And this hospital is the bridge. Most of the centres that are that are around the world today that offer quote unquote alternative or integrative therapies really dismiss standard of care. And I test everything. We never guess. My mantra is test, assess, address, don't guess. So when you talked about where do we start with a patient, we don't start doing anything until we know that patient. And we know that patient literally inside and out. And I want to know what makes that person tick. I want to know what brings that person joy as much as I want to know what their tumour burden is, right? They're both integral to that patient's success in a positive outcome, in a different outcome. And so a a typical consult with one of my trained physicians is going to look like, you sign up, you know, before, in fact, all my doctors require their patients to read, this sounds like a terrible plug for my book, so apologies if that's how it comes across, but the educational aspect of the metabolic approach to cancer book that my, my self and my co-author, Jessica and Kelly wrote, gosh, May 2017 is when it came out. Still the best-selling book in the cancer world today, but it's a manual. It's a manual for folks to start to evaluate their own terrain well before they even consider making an appointment with somebody like this. So most patients that come to us, they seek us. We're not putting out a shingle and advertising. We don't need to, sadly. I wish that was the case, but there is such a demand for this that people stumble across this and it makes more sense to them than what they're being offered. So folks are able to evaluate for themselves what might be driving this process. And then they can start making those changes before they even, you know, have that first visit with the with the doctor. So at that time, the doctor will require that book to be read because there's so much education in that. And there's a questionnaire at the beginning, we call it the terrain 10. It evaluates the what I call the ten drops in the bucket. So your epigenetics, which is above the gene, the the things that have been passed down to you that you have the power to change their expression. Your metabolic health. So what are you fueling this container? You know, what are you feeding this container to help it, to help it move down the road? The environmental toxicants. I mean, it's no longer a matter if you have toxicity, it's how bad is it and how does it interplay with your terrain? Number four, the microbiome. Huge, right? I mean, even Hippocrates said that all disease or health begins in the gut. And so we're finally catching up with the science around that. Number five, the immune system. If you live under a rock, you might, you know, you're likely have heard that the immune system is a key player these days as we're dealing with a global pandemic of very dysfunctional immune systems. We should not be being taken out by a virus, right? That's something within us that's having problems meeting that virus. And then inflammation. My goodness, we're considered the inflammation nation these days. Circulation and angiogenesis. So meaning how is the blood, you know, how's the blood circulation and how is the oxygenation of your tissues and how are you feeding the cancerous processes through building of new blood vessels? And then we look at the hormonal balance. Today, we're all swimming in a swimming pool of endocrine disruption, xenoestrogens. Everyone's estrogen dominant, men, women, children. None of us are truly deficient. And so the deficiencies are being, we look at it as a deficiency and then we want to supplement people with these things, but what it really is is about how we're metabolising our hormones. And that also is based on our epigenetics and our other toxic burdens, etc. And then the last two are biggies, are stress and circadian rhythm. Like how are you meeting the cycles of your life, the cycles of the day, the cycles of the season? And then finally, mental emotional. It's a tenth drop in the bucket, but it's a big drop. And a lot of people, they'll do all the tangibles. They like to start there. And those tangibles can only take you so far until you clean out the emotional debris, you won't truly be able to meet your your best self. Because even those psychological hiccups are impacting your immune function, are impacting inflammation, are impacting epigenetic expression. And so you have to deal with all those things. So they take a good deep dive into the terrain. We do a bunch of labs to get baselines. If possible, we have blood blood biopsies and tissue assays on top of the pathology. We also do some functional testing to see if there are drivers. I mean, depending on the person's terrain 10, we might start with doing some deeper dive into their environmental toxins or deeper dive into their hormonal metabolism processes or deeper dive into whatever is showing up in those ten drops in the bucket. And then once we have a a really beautiful full picture of that patient, then and only then can we start to bring on treatments. Because you have to apply the right treatment at the right time for the right person in the right situation. And even at the right dosing and the layering of how you apply those. Because this is tricky, tricky territory. Cancer cells, they morph quickly, very, very quickly. They're smart. They are on the move. And the second you try to put some pressure on them, they find another work around. So in doing this approach, we can get a good sense of where to start and then we test the patient monthly during their cancer process for upwards of two years. I mean, once they've become in remission, depending on the type of cancer they had and how aggressive it was, we may check monthly or at least quarterly for up to two years after they're stable or in no evidence of disease, but we never guess. And you don't have to. And so that's the methodology. I'm teaching doctors a methodology. I'm teaching patients a methodology and I'm teaching patient advocates a methodology to know how to test, assess, address, don't guess. So they don't waste precious time and precious resources on therapies that were not a right fit for them.

Sakina: Wow, it's it's really interesting that you you take into consideration all these systems. Even circadian rhythms, I've actually we haven't heard a lot about that with cancer. Circadian rhythms separately, yes, we've talked about them on the podcast quite a few times, but with cancer and looking into it when it comes to cancer treatment, that is fascinating. I'd love to hear more about that. But there's so many things that I want to dive into. So there's, yeah, there's definitely, you talk about environmental toxins. So that's one that we talk about a lot, the fact that everything is toxic in our environment. Could you give us a bit more about common toxic products that we use and how we can maybe some action tips on how we can reduce them and replace them, maybe taking into consideration the expensive side of things and maybe the overwhelming and anxious side of things where everything feels like it's toxic. So how do we handle that?

Dr Nasha: Sure, sure. Well, one of the things that people can do, at least in the US, I don't know if you can do this in other parts of the world, but you can actually type your zip code into, you know, into a database. And you probably, they probably have a European version of this as well, UK version as well, where you can type in your zip code and you can see the air and water quality as well as the sort of industrial exposures and the environmental agency exposures that's around you. So you can get a good sense of how close are you to living on or near places. So for instance, in my pristine little town of Durango, Colorado, in the mountains, we have seven known carcinogens in our city drinking water. We have twenty-four possible, right? We live in an area that is some of the highest levels of radiation you're ever going to get just because we're in the mountains. It's just naturally coming from the earth from all these old, all these minerals. We have the highest levels of arsenic for the same reason. We have the highest levels of mercury because of coal burning plants all around us. We also have a lot of gas and oil industry around us because there's a lot of good resources. Wherever you see a lot of minerals in the soil, you're going to get things like gas and oil. And so we have that showing up. So when I test for patients, you see these high toxicities of certain metals or or chemicals or solvents that are incredibly known. I mean, even IARC, a huge agency that's a third-party agency of testing cancer. And so we're literally swimming in that. You would never expect it looking around at the sheer beauty of the place in which I live. And so patients need to take it in their own hands because no one's going to do it for them. So they need to explore what they're living around. If you live on a golf course, you're poisoned. If you live near a campus, like a hospital campus or a university campus, you're poisoned because they spray these with enormous amounts of herbicides and pesticides to, if you if you see a beautiful green lawn, that's not nature. Okay? Unless someone is out there plucking the weeds themselves by hand, that is not natural. You are getting chemical toxins from that point on. So just know that. The other things are just again, in the largest organ of absorption and elimination. Most women by the time they walk out the door in the morning to go on with their day have already put over twenty different chemicals on their body. And it is most of those chemicals are coming in and locking like a like a lock and key process into these receptor sites within their body that are scrambling the information of how their hormones are going to work or not work. So women who think they're dealing with hormone deficiency, they're dealing with hormone scrambling, hormone metabolism problems. And so that's more of the issue. And a lot of it is because every little garage, every little receptor is loaded up with all these other chemicals that are competing for the sites of your exogenous hormones. So that could be the glyphosate. Now, not as much in parts of Europe as we have in the US, but now the rainwater worldwide, everyone has glyphosate poisoning, you know? Organic does not mean anything anymore because you cannot, a field does not, you know, somebody labelling a field organic and the field next to it not organic, glyphosate moves, which is Roundup, as people might know it as that, two miles, you know, four kilometres or so, four to five kilometres, by air, water and soil. So, and then when you, when you store these things, it's, you know, it it's like it just concentrates even further. And then the interesting thing about a lot of our food sources, especially the grains and the legumes, they they are natural sort of chelators in the soil. So they draw that stuff up. And so even organic, between what's falling from the sky, what's spraying from two miles away, and what's being sequestered in the soil is coming right up into those food food sources. So where then ingesting them. So I really recommend everybody gets a a glyphosate test because it's kind of frightening. I mean, we know it's a known carcinogen now. So if I see somebody with a blood cancer like lymphoma, I'm looking for glyphosate first. So those are just some examples. So the skin component, you need to be able to literally eat what you're going to put on your skin. You need to be able to read that label. The parabens and the phthalates, these things are so highly toxic. And so the skin piece, and then the water. You know, this is the place, your Brita or your refrigerator filter is not going to cut it. It definitely doesn't take out fluoride. It definitely doesn't take out heavy metals. It just takes out maybe a little bit of chlorine and maybe a few microorganisms, those little ones. So you have to start to think about whole house water filtration. If you're a big bath person or if you soak in hot tubs or pools, you need to filter that because again, it's going to come right into your skin. And you at least need to highly filter, quality filter your water. So things like a Berkey, if you're in a place where you can't put one under the sink. And so the expenses can be anywhere from sixty bucks for a good like Berkey travel water filter all the way up to several thousand US dollars for a whole house water filtration. That is the most important investment you can make in your health is just the quality of your water. And then just get outside and sweat, you guys. Move your body, sweat this out. Get your organs of elimination working. Make sure you're pooping every single day, at least several times a day. Make sure you're hydrated well, making sure your kidneys are functioning, making sure you're sweating, making sure you're breathing well, getting working up good breath. Those are how we take out the garbage. If you are not doing those things every single day, things are backing up inside of you.

Sakina: I'm glad you brought up the natural detoxification systems because I feel like all this information, although it's essential we have this knowledge about the toxicity of our environment, it can feel so overwhelming because you have so many things to think about. Our nutrition, how we eat, which we talk a lot about on this podcast, but also, yeah, the environmental toxins, but then also just life, work, children, social life, all these things. So how do you handle managing worries and feeling overwhelmed with all this information and all the stress of having, of knowing that everything, a lot of what we do can impact our health like that?

Dr Nasha: I love that question because I think again, it's one that's really under, you know, under-evaluated. And with this piece is stress is not going to go away. It's just the nature. If you live in a westernised culture, western environment, you have a certain set of stressors. If you live in a developing or an underdeveloped environment, you have certain stressors. Stress isn't going to go away. How we meet it, how we respond to it, and our inner resilience with regards to it are what we have control over. Okay? So that takes practice. This is not just like inherent. You have to work at this. Just like people go to the gym, you have to work out your mental resilience muscle as well. And so you must take on a practice, a practice of mindfulness, whether that is a spiritual practice, a meditation practice, a walking meditation, a few moments of just sitting and breathing. You have to get clear. You have to tune into yourself. Most of us are walking around with just like disembodied experiences. We don't even know what's happening inside, especially since most people who come to me, well, not most, I would say all people who come to me say, I don't understand why I got cancer, I'm so healthy. Now, that is literally impossible. It is absolutely impossible. So what that tells me when someone tells me that is they have not inhabited their body for a very long time. And so that's one of our first starting points is get back inside. So I love some of the mindfulness practices that have you lay down and maybe tune into your toes and then tune into your ankles and work your way all the way up to the hair follicles and everything in between. See what messages, because we literally have messages coming our way all the time of what's going on and what we need to do. And we ignore them. I have a patient who says that we're really good at putting the sticker over the check engine light on our dashboards. And then we're we're like, ignore, ignore, ignore, ignore until the until the vehicle falls apart on the side of the road. That is us. That is what happens when you end up with cancer is you've been ignoring that check engine light for a very long time. And a lot of that comes down to how you're managing your stress. One piece that people don't understand when they're looking at how to manage stressful situations is to look at your support system. We are an expression of the five closest people around us. So frankly, if you're hanging out with a hot mess of people, you're a hot mess. Okay? So some of the best things you can do to recover your health and your mental awareness is to change your social environment. And it's also one of the most difficult because for a lot of reasons, right? And so people need to look at, is their relationship causing them undue stress? Do they have a partner who's willing to do the work with them in order to collectively change that experience? If not, you need to get out of that. Because I always tell people, you know, people like, I always feel like maybe it's my fault that I got cancer. It's it's never someone's fault. We don't know what we don't know until we know. But once you know what your obstacle to cure is, once you know what your trigger is, sitting, you know, sitting there eating a glyphosate-drenched meal knowingly is just as crazy as staying in a very toxic relationship knowingly. Once you have that information, you need to go to the steps to change it. So either change the relationship or leave it if it's not possible to change it. That's down to relationships with family, friends, loved one, your partner, work relationships, all of those pieces are critical to your health and well-being. Because your vibration can only go as high as those around you. So if you're with people that are constantly flowing at this level and you know it's somewhere up here for you to actually attain what you need to attain in your own self-development and your own health and wealth and well-being and psychology and vibrancy, you have got to get out of that cesspool and move into a different environment. And so that's really critical for people. And I think one of the levels we don't evaluate enough in how we're managing our stress. And then you make different choices. Every moment is an opportunity to make a different choice. So when you're looking out there, for instance, at the at the basket of fruits, they look beautiful, but I would put money down that all those apples, which are in the top twelve dirty dozen every year of pesticide-ridden things, no way would I touch that apple with a ten-foot pole unless it was organic. And then I look at the bananas. Those are like a giant sugar bomb. So for me to look at the apples and the bananas, as hungry as I may feel, it's better for my health to actually choose to not eat anything than to put one of those sugar bombs or poison bombs into my system. So those are the choices we make every single moment that we can pivot differently. If someone is behaving really rudely to you, you have a choice to take it on and feel it, internalise it, or you can acknowledge that they may be in their own process and their rage or their rudeness is based on their own pain and has nothing to do with you. And then you can pivot and choose not to react to that and simply move on. Those are examples of how we get into a mindfulness practice and some days will be better at it than others.

Sakina: Yeah, that's a good way to end it for sure. Yeah. No, it's very interesting the the impact of group to drive change and the fact that everyone in your circle can contribute to this these lifestyles and these choices that we make every day. Um, it is definitely difficult to do every day because there there are a lot of choices and they all accumulate throughout the day so it can be quite tiring, right? Um, but on social media, you talked about sugar cravings. So I was wondering because you were talking about the fruit basket, um, if you have any tips for that, because obviously, we do know what's good for us and we do know that we should be avoiding certain things and making better choices and informed choices. But when you have those cravings, that sometimes can take over your brain, what do you do and how do you manage those?

Dr Nasha: Well, when the cravings come up, the first thing I encourage people to do is drink some water. Okay? Most of the time our cravings show up because we're all walking around chronically dehydrated. Now, preferably quality water. Exactly. Shall we cheers to that? Okay. Preferably quality of water. Um, but you start there. You wait fifteen minutes. If the hunger is still there, you probably need a little bit of protein. Okay? Our tendency is to go and grab an energy bar, which it'll say high protein, but it's also like ten times the amount of carbs. So it might be that you go grab a couple of pecans or a scoop of almond butter or a hard-boiled egg or a little piece of if you if you're someone who tolerates cheese okay, then a little piece of quality cheese or a little like organic jerky, like something that can like give you just a little protein fix, okay? Then you wait fifteen minutes. If you're still hungry, then you might need a little bit of fat. Okay? So I'm walking people through the process, dehydration, protein, fat. Those are what we need first before we ever need a carbohydrate. If you're still hungry when you get down to that carbohydrate, nine times out of ten, it's an emotional trigger. Okay? So we will reach for sweets when we're not experiencing sweetness in our life. Okay? We will reach for the sweetness of food because of the lack of sweetness in our life. And so that is huge. And so in that moment, when you reach that point and you're like, okay, little fat didn't do it, little protein didn't do it, the hydration didn't do it, then you can be very tender to yourself and say, I know where this is coming from and it's okay to go ahead and eat that banana or that biscuit or whatever it is. But having the awareness says, please, you know, it's it's not to condone those things, but it's to say, I understand I'm tender to myself and I know I have work to do in this area. And so that's something I want people to start to recognise is our food hunger, no, none of us are walking around starving. Okay? At least in the Western culture. Well, we are nutritionally at a cellular level, but not on the the abstract, like the, you know, the the superficial level of true hunger. That that physiological hunger really you cannot achieve that until you've gone at least twelve hours without a meal, right? So unless you've gone twelve hours without a meal, you're not really hungry. You're hungry for something that's missing in your life or in that moment, or you're medicating something that's really uncomfortable for you in that moment. And so that's where taking a walk, having those little, like I said, the food, the, you know, the water, the protein, the fat, calling a friend if you need that support, writing, journaling, you know, looking at pictures that make you happy, listening to some music, dancing it out, shaking it out, doing some buteyko breathing methods or a little nitric oxide dump process, something that distracts you for a moment and resets and recalibrates those neural pathways to remind you that you're safe, you're loved, and you're held in this world. And that you can do this and it does not have to be taken care of with other addictive patterns. And then get the support you need to help you address those firsthand.

Sakina: That's, that's really interesting. Is addressing the need instead of just filling it with the food. Um, when it actually won't meet your need in the first place because you're seeking pleasure often, we're seeking pleasure and care and just a sweet time as you said. So having that moment to pause and address that need, understand that need, even if you end up eating the cake or, yes, just having that moment to understand, is it, what do I need in this moment? Is it that I'm hungry? If I'm hungry, what am I going to reach for? And if it's not that I'm hungry, what are the tools do I have to give pleasure or love or care to myself that is not necessarily something that will not make me feel that good.

Dr Rupy: I really do hope you enjoy listening to that interview with Sakina and Dr Nasha. I do hope we get a chance to speak about mistletoe therapy as well as environmental medicine in a bit more detail, and I will personally be diving into some of the topics a lot more my side as well. I will see you here next time.