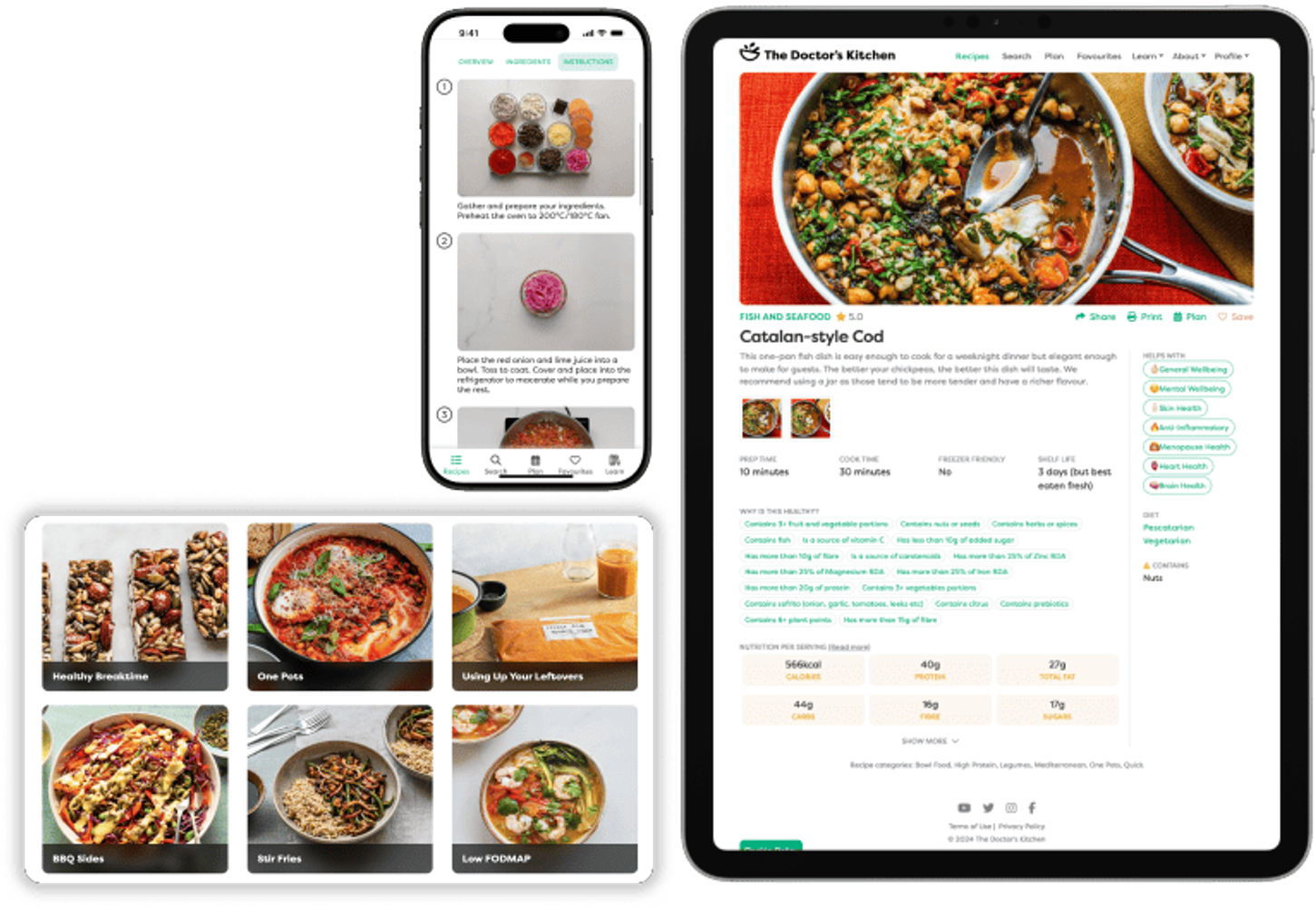

Dr Rupy: Now, even though I'm a sceptic, I love health tech. I wear a wearable, I play with red light therapy gadgets, and I monitor my bloods more regularly than a lot of my peers. But rather than being overwhelmed with the data, I thrive in it and I'm able to reasonably weigh up the information from all these inputs because of my experience of being a medical doctor for over 15 years. But with so much interest in health tech, the landscape has become super confusing and it can be super hard to separate health from hype. So that's why we're chatting to Lara Lewington today. She's covered some of the world's greatest innovations, presenting the BBC's flagship technology show, Click, and many, many more. She's explored artificial intelligence and health, the use of home hormone testing, and whether there are any devices that can actually help us meditate better and stress less, something I'm definitely interested in. This is a super fun episode where we discuss what tech is actually available today that can help us eat, sleep, and exercise better, as well as stress less and prevent disease. And I learnt both about the world of breath testing to guide our food choices and an app to help me with jet lag, and the potential for intelligent and personalised cancer screening. Hacking Humanity is Lara's book and it dives into a lot of what we discuss today plus a lot more, and it's available in all good book stores right now. And just to make it easy for you guys, I listed some of the products that we discussed today in the podcast show notes. So whether you're listening to this on Apple or Spotify, give us a follow if you haven't already, it helps us boost up the algorithm. To make it easy for you guys, I've listed some of them that we discussed today. We don't have any affiliation with any of them, but I thought it might be interesting for certain people who want to do their own research about the breath test that we mentioned or the MRI scanner that we mentioned, for example. So you can check them out all there as well. And whilst you're there in the podcast show notes, you'll be able to click the link to get a free bag of Exhale coffee. If you're into delicious, healthy, high polyphenol coffee that is roasted for benefits and delicious flavours, I'm drinking one right now, check it out, you'll get a free bag of Exhale coffee that they will send to you directly. And you can also check out the Doctor's Kitchen app recipes. We've got a whole bunch of new recipes right now for February and they are absolutely delicious. I pull up the app myself every single week. I see what's new or what's trending. I click on it, I send it to Rochelle for sign off, obviously. I go and get the ingredients and they are absolutely delicious because they're created to be high in protein, high in fibre, high in anti-inflammatory ingredients and taste delicious. And we've tested them a whole bunch of times in the Doctor's Kitchen studio so you can be assured that they work and your family will absolutely love them. Go check it out. You can find it on the doctorskitchen.com or on the Apple and Google Play store as well. For now, this is my wonderful conversation with Lara Lewington. I know you're going to love it. Lara, great to have you in the studio today. I wanted to start actually by, why don't you give us a bit of background into how you got into your career? You know, you were just telling me that you used to do shifts and I don't know what kind of shifts they were, but you know, what, tell us a bit about your your career trajectory up until, you know, writing this awesome book, Hacking Humanity.

Lara Lewington: Sure. Well, I spent the past two decades covering technology and innovation. Before that, I actually started out as a weather girl in my early 20s.

Dr Rupy: Oh, really?

Lara Lewington: And a chauffeur's reporter for Channel 4. So I've had a variety of experiences. And as the years passed, the technology thing used to just be a little bit of a hobby on the side that for Channel 5 I'd do these gadget reviews separately to my main job. And then eventually that became my real job. I'd contacted Click at the BBC because I loved the show, was really into the content, and was delighted when they got me to do my first piece, which was about sleep. And at the time I was doing the weather, working shifts, so I knew a lot about sleep and lack of it. And this was the beginning. It went from making a few pieces to becoming a presenter of the programme and I was then there for 15 years. And alongside that came the opportunity to do loads of other tech stuff, Panorama, Tonight, Woman's Hour, and I've been covering technology in print, TV, radio now for quite some time, and then came the book, which was the culmination of the whole journey, I think.

Dr Rupy: Amazing. So you must be a mini expert on sleep if you started doing sleep for BBC Click and you're a shift worker, or used to be a shift worker, and you just got back from CES, so you know, you're very well accustomed to jet lag. Like, what, give us some of your sleep tips to start us off.

Lara Lewington: Yeah, when I arrived here this morning, I told you I just had a triple espresso, so I might be talking very fast, but at least I should be awake. Yeah, just got back from the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, which I've been to every year for the last decade now. And it's always a brilliant start to the year because you just see how the next year is expected to play out and also where we're at with tech. I walked around this enormous show floor, which it's really hard to explain the scale of it. It is so massive. And what was really noticeable this year was next to every stand, whether it's a massage chair or Withings health tech, it says AI next to it. Everything claims to be powered by AI. I think the term is overused. Often it's used just to try and add value to something where it's not really relevant. But there's this weird relationship that we have with it, which was a real driver for why I wrote the book on health and AI as well, in that people really fear it, but at the same time, companies can't wait to tell you that they're using AI. So that was definitely a big theme of CES, as was the idea of robots doing our housework. Now, I think we are quite a long way off this being a reality for most people.

Dr Rupy: Yeah.

Lara Lewington: Yeah, I was watching one trying to do the laundry and it was so slow, I wanted to jump in, push the robot out the way, which of course was not the idea.

Dr Rupy: How far, this is going to take us on a bit of a tangent to start us off with, but how far do you think we are away from robots being commercially viable enough such that most households can afford them? Because there is this idea that's propagated by, you know, people like Elon Musk and a whole bunch of other tech entrepreneurs in the space who are saying, you know, it's going to become as affordable as a small car and it's going to be able to do some of those, you know, tasks, whether it's laundry or, you know, the domestic work that we currently rely on to do either ourselves or we pay people to do for us.

Lara Lewington: Yeah, you are absolutely spot on with the kind of people in the tech world who talk about this. The reality, I think, is somewhat different because robots find it quite difficult to do a lot of things that humans find easy. I was at MIT last year at their labs where they are trying to recreate those basic household tasks by robots. And the robots were really struggling. There was one where a robot arm was trying to make a sandwich and it kept on trying to pick up this bit of lettuce and this bun and the ham was thumping down on it all and it was moving all around. I wouldn't want to eat that sandwich after that robot hand had been playing with it. And even when we saw the robots at CES that were trying to do the laundry, it was looking around the room to map the space, see where the laundry was, work out where to pick it up. This is all taking a lot of time. Then trying to go to the washing machine, but the thing that it took a lot of training to do was to be able to open the washing machine door, something that we don't even think about. And the other question is, is it a humanoid robot that would do all of this? It's not necessarily the right form factor. Now, some people working in the world of humanoid robots say, well, the world around us is built for humans. It's built for that shape and size. So they are right. But actually, what about going up and down stairs? There are a lot of limitations to these robots. Really high cost right now. And also, a lot of the demos that we see are in very controlled environments. And it's very easy to watch what they're doing and imagining this robot's going to just appear in your home and do it, but I don't think that's the reality. Plus, when I've been going around talking about AI and technology for health, and I've talked about the power of activity trackers, which is something I'm sure we'll get on to in due course, a lot of the response I'm getting from people is, isn't this really exclusive? You've got to spend a lot of money to buy an activity tracker. Activity trackers, you can buy something for 30 quid that will do a good job. Whereas you're talking about the realms of what a robot would cost and it's a completely different ball game. So they will be in some years time, probably there in some high-end homes, but the idea of them becoming the norm, I think we are a very long way off.

Dr Rupy: Okay. So what we're talking like 20 years?

Lara Lewington: Oh, if ever. Okay. Well, it's hard to put a time frame on it, but you've also got to work out what they're going to do because you probably don't want them doing just the laundry. You want the cleaning and the laundry. You want a device that would do multiple things. Maybe you have a device that has the bit that will mop and vacuum the floor, then has an arm which will come out and clean the windows or do something else. Because in isolation, those things exist now. You can have a window cleaning bot, you can have the mopping bot. And the mopping one was actually quite good when I did a big experiment years ago with the vacuums and the mopping. I was quite impressed by that. It's basically like a wet version of the vacuum. And obviously these things get better and better, the cost comes down, you get competition from companies that can make them at a lower cost. I don't know how mainstream the entire cleaning operation of a house by a robot will be going.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, yeah. It's a big market. So at the start of your book, Hacking Humanity, you set the scene for what a morning routine could look like with all of these gadgets. Could you set that scene for us now and then perhaps what that might look like from a health and wellness perspective in the next five or 10 years?

Lara Lewington: Yeah, I think one of the main things here is the seamless tracking of our health and life. And we don't want to feel like tracking our health is taking our time or energy. It would be great if it could just happen in the background. So this picture that I paint is of you waking up in the morning, going into the bathroom, looking in your mirror, which is a smart mirror. So it might assess your blood pressure, your risk of type two diabetes, how well you've slept last night will have been tracked through your mattress or through a wearable, and all of this data is being collected. You're having this morning sync of all of it. You go to the bathroom, there's even something down the loo tracking everything. All of this is happening in the background. And if something is amiss, an alert will go off. This may require you to charge 14 devices. And there are probably elements of it that will seem very desirable and bits that won't, because the important thing here is all of this is really possible. It's incredible what we could actually find out about our health through seamless tracking in the background. But how much do we want to do that? How much of that information do we want and how do we not get obsessed with staring at that data? So the idea of it happening seamlessly and our baseline pattern, so what our normal is, being something which is collected so we can see if that pattern changes, if something goes amiss. And that's where we look at the data, that's where we look at what may have caused it or potentially the need to make changes.

Dr Rupy: So this sort of seamless morning, at the moment, I mean, I wear, you know, a tracking ring, I've got a whole bunch of devices that I look at in the morning. I'm not like a Bryan Johnson, but like I'm somewhere along that spectrum where I'm intrigued by my health data and it does guide some of my behavioural choices. But there is some friction involved in that. Do you think the future is going to be what it's just seamless? You get like an update almost like a BBC news feed on your phone and it gives you the top line things that are the most impactful and very easy suggestions based on your own personal data.

Lara Lewington: Yes, I think the idea of something like a mirror, which is something that I'd filmed at CES a couple of years ago, where it's very early days for the technology, but through tiny movements in blood flow in the face, it's correlating your data to the data of those, there were 40,000 people it was trialled on, the one that I filmed with originally, who had health conditions to be able to sync up those tiny movements with the likelihood of having a health condition, so to be able to figure out risk. So technologies like that where it's not directly about tracking you or taking your measurements can sit alongside the ones that do and we'll start to understand more and more about risk. And so if it's something like that, if it's maybe some scales that are built into the floor of your bathroom that you're not even thinking about stepping on, this is something that Withings have demonstrated in concept stuff each year over the last few years. So all of these different elements of data, which I think right now, even though some of the technologies have been proven to work fairly well, a lot of it is still conceptual. And the idea of pulling all of this data into one place, air quality, so many other things that surround us, our lifestyle and our behaviour, to really start to understand more about the correlations of how it impacts our health and longer term, seeing all that data together, understanding who is at risk of what, when. And this is where we start to be in a position to better be able to predict the risk of illness. And if you can predict it, you can potentially prevent it or at least discover things early. So the power of this data is huge. And I think what is really, really important here is I'll go back to the idea of this baseline, understanding what our normal is. Because for me, wearing an activity tracker is nice to see that I've been active enough and to make me walk home instead of getting the bus if I feel I haven't done enough. It's a nice little push. But I also know I'm pretty active. We know whether we're active or we're not. So maybe it's more important than how many steps we did yesterday, the idea of understanding what our normal is over time. And there have been countless cases of people seeing something has been amiss in their data, in their heart rate, in their heart rate variability, and they've gone on to see a doctor and said, look, things aren't looking right. I've seen these movements in my data, and they've been diagnosed with heart conditions, even cancer, episodes of lupus. There are now many cases of this where they're not medical devices, they're not there to diagnose, albeit they do have some medical grade sensors in them, some of the brands do, but they just allow people to see a little bit deeper into their health so they can see those signs of something just not being right and look into it further.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, yeah. I definitely see the use of some of these devices in a predictive manner and for prevention. I guess the big thing, and maybe we're skipping a few steps here to go right to the end, but it's it's getting people to actually make the action. And this is where you see a lot of scepticism, particularly within the medical world of all of these devices and all of these different sort of projects because if people aren't eating the right food or choosing the right foods, if people aren't moving, like you were just talking about, you know, nudged in the right direction, or they are financially insecure so such they can't make those choices, then this is kind of like much to do about nothing. Like what what do you say to those kind of sceptics and and how do we navigate that?

Lara Lewington: Yeah, totally. And I actually think there's a lot of truth in what you've just said there that I've travelled the world and spoken to the greatest scientists and medical researchers on earth, but all of them, all of them without exception, no matter how incredible it is what they're creating, come back to this idea of lifestyle, of the power of what we eat, sleeping well, exercising, and that we're getting the right types of exercise and social connections, our interactions with each other are so important. So no matter how advanced the scientific breakthroughs or the technology is, we can't ignore that. That is still so important. If exercise was discovered now as a medicine, we would all be talking about it being an absolute major breakthrough in human understanding. So we can't expect magic here. All of that is so, so crucial. And what I feel is that technology helps us understand what matters, what we're doing, log what we're doing, but also not just to log what it is, because you could write that down in a notebook if you wanted to, but actually see its impact on our bodies. See how our body is responding to any changes that we make because we're all different, we'll all respond differently to different things, as you well know. So I think that's crucial. And that's actually why I start the book on where we're at with that now because there is so much information out there that people can get really, really overwhelmed. You can't do everything that you're told to do. You can't eat all of the different great things you're meant to. You'd be too full up, it would be too much food. So it's how do you do enough of the things that are right for you? How do you track those, see the impact on you? And look, not everybody is fortunate enough to be able to spend the time worrying about that. There are many people who are just worried about getting food on the table for their families. And that is an absolute reality. And the education for people to know how important it is to think about certain things. This doesn't need to be expensive. It doesn't need to be expensive gym membership. It can be doing some really basic exercises with your own body weight. It can be going out for a run for people who are able to. But naturally, there are a lot of challenges that surround this. When it comes to sleep, there are people working shifts, there are people caring for someone with childcare responsibilities. So it's taking on the things that we as individuals can do and that we can maintain. There's no point in doing something for a week. The tiny change that you're going to keep long term is way more important.

Dr Rupy: Totally. Yeah, yeah. I think with that caveat acknowledged, let's dive into some of the tech around those key pillars of lifestyle that we all know are so important and we bang on about every single week here on the podcast. So diet. So I'm really interested in technology that can improve people's awareness of what diet suits them. At the moment, I think people fall for particular narratives online. You know, people, a lot of people can benefit from ketogenic diets. In fact, I'm going to experiment with a ketogenic diet myself, but I'm going to do it in a way that is truly ketogenic with the guidance of a dietitian and with ketone monitoring, continuous glucose monitoring and blood monitoring, looking at my cholesterol levels and how I respond to certain saturated fats. But a lot of people are following keto diets because they've seen someone online or they've heard about these, you know, magical benefits of a particular diet. But when it comes to diet, I think the holy grail is determining how one figures out what diet is best for them. And there are a few technologies that you talked about in the book, including microbiome tests, breath tests, or even blood tests as well, that can help people navigate this like kind of murky landscape, assuming that we've removed ultra processed foods and we're eating within an energy balance as as sort of the first step.

Lara Lewington: Yeah. So I suppose the first thing to say here and in terms of any of these lifestyle factors is if you're doing something in a really poor way to start with, a small change in the right direction is going to make a huge difference. And once you start to get towards the healthiest end of this, it's of course harder to not just reach a point of diminishing returns. So when it comes to diet, I think as you've alluded to there, there are a few different technologies. Now, Omed, which was the breath tracking which you just mentioned, I think is probably one of the things that excited me the most here. So

Dr Rupy: Omed.

Lara Lewington: Yeah. So the company making it do breath tests and lactose and fructose intolerance testing, which is provided by the NHS. So you've got a really strong tech company here doing this. And the idea is that for people, and this is currently through a GP at the moment that this would happen, is that for people who are not fructose intolerant and not lactose intolerant and not gluten intolerant, so you've ruled out all of those specific things that are understandable, but they're having really real digestive issues. And this is so many people. We know how common IBS is. Just people who are struggling, but are struggling to actually figure what it is that's irritating them. Well, breathing into this device a number of times a day allows you to quantify through chemicals in the breath how your body is responding to different foods. So instead of you just making notes, which can be really difficult and also you don't necessarily know the ingredients of everything you've consumed, it can help take you to a point where you understand what it is that you've eaten that is bothering you and so you might know it's something you should avoid. At the moment this is being done alongside a GP. So it's fully supported. And this is something that in my book I'm really passionate about that everything is, there are 1500 citations from medical papers. I write this in the beginning. And no reader needs to read them. I've done it so they don't need to. But I'm interested in real science and where the technology is really working. It's really easy to just believe the press releases and get caught up in a whole load of stuff on Instagram. And people want to believe and they want to see a great solution. But the technology that I've seen that appears to really be able to make a difference to people is interesting. Continuous glucose monitors, of course, had a lot of publicity over the past few years. And I know some longevity enthusiasts using them long term, but for most people who are not diabetic or pre-diabetic, then the use of one for a couple of weeks, I think is an interesting insight into your lifestyle and diet. And a few useful things that I took away from this experience. I am not a doctor or a scientist. And so when I approach testing all this stuff and all of the people I've interviewed and everything I've done, I feel like I'm hopefully doing it as any member of the public who is just interested in this would. And yes, I've tested everything, but I also sort of feel like, you know, I have no agenda on any of it. This is this is just what what I'm testing and my my results. And my feeling from using a continuous glucose monitor for two weeks was I discovered that the vegetable juice I was making before lunch, now this had no apple in it to cheat, this was pure vegetable, was the biggest spike of the day I was having. Whereas one of the two weeks that I used it for, I was actually on holiday for a week of that, and after dinner, I'd be eating an ice cream whilst walking back after dinner and I didn't even go out of range from my ice cream. So probably I'd had it after my meal. There's also a whole thing of what order you eat your food in, having your vegetable first, keeping your carbs and sugar to the end. And I wasn't going out of range. Now that's not to say ice cream's good for you, vegetable juice is bad for you, but it's all about the order of what you're eating it in. And as you'll know, taking fibre out of something changes the impact that it has. So I thought this was a really interesting finding. And

Dr Rupy: What was in your vegetable juice?

Lara Lewington: It was, oh, I can't remember exactly, but it was

Dr Rupy: Did you make it yourself or did you buy it?

Lara Lewington: Yeah, well, it was a mix actually, but I was deliberately getting them without fruit. So kale, spinach, cucumber, celery, these were not wildly sugary things.

Dr Rupy: They're very low in sugar. Yeah.

Lara Lewington: But on an empty stomach after a workout often.

Dr Rupy: Ah.

Lara Lewington: And this was the other thing, seeing blood sugar go up when I'd worked out.

Dr Rupy: Oh, yeah. Yeah, yeah.

Lara Lewington: Yeah. And now I understand that's normal.

Dr Rupy: Yeah.

Lara Lewington: But it's not necessarily what people expect. And I talked to other friends who had tried a continuous glucose monitor who were saying things like, oh, my blood sugar was going up and down. Well, it's meant to go up and down somewhat. It's not meant to stay level. But it's about moving out of that range. So I came away from it feeling like what's interesting is you learn a bit about your individual habits, no matter what end of the scale you're at, because obviously we know you eat a big dessert or lots of chocolate, lots of sugar, and it's not going to be great for you. But it's just learning those things that go beyond that. And so there's the personalisation element, but I just felt like you can take away from a couple of weeks a bit of information. Did I change my habits? I did slightly change the order in eating food. They give you bread in a restaurant before a meal. That is so bad for your blood sugar. And I now have this consciousness every time I'm in a restaurant and bread is presented, I try and resist. Of course, I'm not perfect, but

Dr Rupy: I miss some of the bread is incredible. It's really hard to just not go for it. I just got back from Australia a couple of weeks ago and we went to this amazing restaurant and apparently Oprah Winfrey had been there a few weeks ago and she'd openly said, this is the best bread I've ever tried in my life. And I was like, what a statement from Oprah Winfrey. So of course we like dived straight into the bread was very good. It was like it was incredible.

Lara Lewington: And if it's warm, how can you resist it if it's warm?

Dr Rupy: Warm bread, freshly baked, you could see it being, you know, made in the wood oven and all the rest of it. But and it was Fred's restaurant in Sydney, just in case people are wondering. Um, but this is really interesting because in your book, I love how you you weigh up sort of the pros and cons of some of these products. Like you openly talked about how continuous glucose monitors are a bit controversial in some circles. There are a few scientists who are really vocal about how CGMs should not be used in non-diabetic patients, how it produces health anxiety. We don't have long-term data to suggest that just keeping your glucose in range is actually going to prevent things like metabolic disease down the line. I personally disagree with that. I think we do have some evidence that high oscillations in your glucose over a day is going to put you at risk of type two diabetes. But you know, there's nuance to the conversation. But I completely agree with you, you know, a couple of weeks using a continuous glucose monitor, as long as you're maintaining your normal quote unquote diet, will give you insights that are potentially actionable and are useful. I mean, like this veg juice thing, that's so unintuitive to me. I would have never have thought that.

Lara Lewington: Totally. Yeah. And there's also the difference between the short-term impact and the long-term impact. And this is something I go into as well, as you've just alluded to, the idea of disease that could be prevented in the future is one side, but there's also just this idea of having the most energy you can possibly have on a daily basis. And elite athletes have obviously been able to do this in the best way that they can for years because it's absolutely crucial that they are performing at their best at a certain time. And it's giving this ability to optimise and perform our best to all of us. And for some people, that may be sat in an office. That's not necessarily going and doing a sprint. But it offers that as well. And how much impact that has on different people will vary and how much people are interested in it. But I would imagine that the reality probably is when it comes to non-diabetics and non-pre-diabetics using these devices, is it's likely to be the most healthy people who are interested. So it'll be those, well, or those who have specific health concerns that are worried a parent had type two diabetes and they're worried that it may happen. So there is there is of course that and that all plays into the idea of preventative health and is incredibly important. But for many people, it'll be those trying to absolutely optimise. And having seen the growth of Bryan Johnson's popularity since I was the first person to interview him about his wellness journey.

Dr Rupy: That's crazy. When did you interview him?

Lara Lewington: Uh, I did it a few years back. I'd gone to his house in LA. I was making a documentary about longevity for the BBC and at the time, no one was talking about longevity yet. I had gone out desperately trying to find people who were interested in longevity and what this movement was doing. And of course, you had people working in the longevity space, but it was nowhere close to mainstream. You weren't picking up a newspaper every day and seeing mentions of it. And I'd managed to track down this great longevity doctor in the US called Jordan Shlain, who's introduced me to loads of brilliant people over the years. And it was just fascinating to see what was going on in the an area of growing and reputable science, like the Buck Institute for research on aging, loads of really interesting studies happening there, but they're not necessarily that sexy to make headlines. But then the sort of wackier side of stuff and trying to figure exactly where the truth is, what is useful, what can we learn from, where is there really a step forward in a developing science and a world where longevity is actually something worth thinking about and what is something that is just still remaining on the fringes. So I was absolutely fascinated to make this programme. And look, the reality is Bryan Johnson is a brilliant character. And what he was doing was fascinating. And each individual thing, this was before his whole don't die thing actually. And back then each individual thing he was doing was based on some form of science. Now, that's not to say the technology he was doing it with or the method he was using works. But it was based on something that should have been physiologically possible. And that was really interesting because when it came to reversing his skin age, he was doing amazingly. When it came to reversing his hearing age, he's got the hearing of a 64 year old when he did it a couple of years ago, maybe now of a 66 year old, he couldn't do anything to reverse it. But if he'd found a way to do so, that could have been really interesting to people with poor hearing. And the fact that he gets all these headlines and he gets all this attention and he gets people talking means that anything that does unfold from what he's doing will be talked about. And going to his house, going to this clinic which he has there was fascinating. The fact he turned a bedroom with an ensuite bathroom and a big walk-in closet into the clinic.

Dr Rupy: A lab, yeah.

Lara Lewington: It was it was brilliant. It was brilliant. And I've been back since and I've seen the whole thing unfold and obviously it's got somewhat more different with the don't die narrative. And I said to him, you seem to have become more extreme. And he said, no, it's just better explained now. Look, he's a controversial character. Lots of people are bothered by what he's doing and they think the idea of not dying is taking this too far and of course, I can see that. But actually, if you sort of move away from a bit of that and just look at some of the experiments, not taking the son's blood. You know, I think that and giving his to his father, that has been happening for years in Silicon Valley. He's just been honest about it. But it's been going on for a long time. There doesn't seem evidence that it's been doing anything useful and he's stopped because he didn't think it worked. But there's there's plenty of other stuff that's going on there that was interesting. And that was fascinating to see unfold.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, yeah. I I find him a really interesting character. I mean, we've had people on the podcast who are really dismissive of Bryan because they think, you know, he's just out to make money, you know, he wants to increase his wealth. And my position is because he sold his company, I think Brain Tree for something like 5, 600 million, something like that. Yeah. So he's close to a billionaire. You don't try and make more money by doing something extreme where it's so much daily work.

Lara Lewington: No, this is about ambition for him.

Dr Rupy: This is ambition. This is pure passion. You can't you can't do what he does every single day in the pursuit of money. It does not exist. Like if you wanted to make money, he'll just give a bunch of, you know, he's a smart guy. Tracker funds, hedge funds, he'll be able to increase his wealth to multiples of billions.

Lara Lewington: I think there's quite a few dimensions to it. He'd been depressed, he'd been through a very difficult time. He feels like this gave him something to focus on and he's been feeling great from it. It's given him some control back. And I think all of that he's talked about in the in the earlier interview with him. And this is he sees it as an ambition. He called himself at the beginning a rejuvenation athlete.

Dr Rupy: I'm not sure if he's still using that term.

Lara Lewington: No, that didn't stick. That couldn't have stuck. So he must have got some like good PR advice about, you know, if you if you call it don't die, it's like controversial and sticky enough.

Lara Lewington: It's controversial, it gets the headlines. But it's fascinating and I think he and I've spoken to many others who who talk like this as well. And it is, yes, it is a bit of an extreme Silicon Valley thing, but they feel like the science and technology are moving so fast, they just want to live through these years healthily because then something else will help them and they'll be able to keep going. And they are also, well certainly Bryan is fascinated to see the future. So he's determined to want to stay around to see what that is.

Dr Rupy: It's all about the game is staying in the game. That's basically it.

Lara Lewington: Yeah. And I absolutely get all of the stuff that that people say about him, but I've made a couple of shows with him and he's been brilliant fun for it. He's been a great sport. He's laughed at himself when he's needed to. And it's it's interesting. Look, it's you try and jazz up programmes about science and you need something fun because once you've filmed in one lab, you've filmed in them all. Labs tend to look the same.

Dr Rupy: Totally, yeah. If only someone could do something for sarcopenia, I think that would be great. I mean, he is doing stuff for sarcopenia because he does a lot of strength training, specific movements that are aimed at the large muscles that typically reduce in size and function over the course of our lives. And we know that over the age of, I think it's 50, or post-menopausally in females, your decline of muscle mass just falls off a cliff year after year. So I think you're right, it needs science needs sexier taglines to bring attention to it, amplify interest and maybe even bring more pharma R&D dollars to it.

Lara Lewington: Yeah, and there'll be incremental improvements. And I think the issue is you want headlines to say something really dramatic, but actually what we're seeing, especially in this area of aging science, is incremental improvement. We'll see small but small improvements, especially at a population level. I'm not dismissing what it means for individuals, but economically for a population, are really important. And they don't make the exciting headlines, but that is certainly where where we're heading. And I think across health in general, and that's why in writing this book, it's all about a direction of travel. And the better future we can all have for our health, partly through understanding how our bodies are functioning, how we're declining, what our risks are, knowing what to look for. All of that is powered by technology, but actually we will see incremental change over the years that betters our health and betters our prospects for what we can treat.

Dr Rupy: For sure. Sticking on the the food train right now. So we talked about breath, we talked about CGMs. What what other gadgets are there that can improve, you know, the quality of our diet or like whether it's our choices or what within that?

Lara Lewington: There's obviously a lot of talk about microbiome. I think it's probably pretty early days for us to talk about what that means for diet. There's a lot of disease association going on there, but I don't think we should rush ahead of ourselves. This is also something that's very important to consider. There's a lot of ability out there for people to test things. We need to make sure how useful what we're testing is. I've had my full genome sequenced twice. And genome sequencing is incredibly powerful when it's for something actionable in a high risk population. So it cost $3 billion back in 2003 to sequence the first person's genome. Now any of us can do it for a few hundred quid. And we can understand a lot about certain things. Genomics England doing some really interesting things here with newborn babies who are at risk of rare disease being able to avert blindness, for example. But there's also when you move into the realms of diet and nutrition, it's really early days for genomic medicine and for microbiome to really understand a huge amount. So there may be elements that we can understand, but we also need to know how much we don't know already. And I don't doubt for a moment a lot of that will continue to unfold. The other technologies out there, well, things like tracking what you eat alongside your activity and so on. And this is something that I've seen a lot over past years. And when I was testing the activity trackers going back a few decades and comparing them all to each other, and there were also the options of my fitness pal types of app type apps where you are inputting all of what you consume. And it can be a really time consuming and slightly painful process to log it all. Well, now many of those apps have progressed to be able to take a photo and it can even assess the size of the portion and the calorie consumption and how much salt and sugar and so on. But actually, that has limitations because if you've got a dressing on your salad, well, it doesn't know anything about what the ingredients are. You can't guess that unless you're putting in something specific that was ready made. And then we're starting to move into the realms of stuff which is becoming more processed. So there are limitations in this in actually logging what you're eating. And as you know, a lot of it is habit. And once we transform our food habits a bit, I think most of us end up looking back at what we used to do and are appalled by our behaviour. So it it's from the technology perspective, I actually think that's one of the harder areas to keep track of is logging what we eat.

Dr Rupy: You know, it's interesting. So I agree with you, the the tracking using snapshots is is really tough. We actually introduced that feature into the Doctor's Kitchen app ourselves. So we have a tracking function where you can take a picture of your food and it will use, I think we use Gemini as the back end. So it will analyse the ingredients it recognizes, passes that information through our nutrition calculator because we don't trust any other nutrition calculators out there. We think they're they're actually really flawed using old data. And that it gives you fibre, protein, and inflammation index using our inflammation index as a an approximation. But it also gives you the ability to edit as well. So it'll give you, if I took a picture of my, I don't know, kale salad, I don't have kale salad every day, but let's say I had a kale salad with white beans and

Lara Lewington: That was right on brand. I was hoping.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, I know. Yeah, yeah. Not every day.

Lara Lewington: I saw what you had for breakfast. It was very healthy.

Dr Rupy: That was the Doctor's Kitchen bread. I'll give you the recipe afterwards.

Lara Lewington: Thank you. I'd love it.

Dr Rupy: But it gives you the ability to like change the quantities or add things if you've added something different. But it is still like a bit of friction for people who aren't motivated to pull out the camera. I forget all the time. I forget to pull out my camera, take a picture of my food. And whilst I know that tracking all 21 plus meals every single week would be great and it'll give me an indication of whether I'm consuming enough protein, I'm consuming enough fibre and give me those actual insights, there is still some friction there.

Lara Lewington: It goes back to the idea of the seamless tracking actually that it's so much harder to do something that requires your time and attention.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, yeah, yeah. I think if I had a wish, imagine we're on Dragon's Den or Shark's Tank, if I had my wish list of like what I wish an entrepreneur would bring to the table, it would be a scanner, either using your phone or something, that allows you to go to the supermarket and scan produce to determine the nutrient density of that produce. Because there is this idea that conventional produce isn't as nutrient dense as organic and there are some studies to suggest that as well. Some produce is laden with more pesticides than others. So it would be interesting to because there's so much, there's not a lot of transparency across that. Like when you pick up a kale or an apple or something, I'd love to just be able to like scan it like, is this actually nutrient dense? Should I be choosing that one over there or from this farm or grown in this particular soil that could be.

Lara Lewington: So the scanning will just tell you what it can do at the moment, you can scan, yes, it's a tomato. But to get beyond that.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, yeah. You haven't come across anything like that, I'm assuming.

Lara Lewington: No, no, the nutrient density, I think would be rather hard for any AI system right now to be able to assess unless of course you had the sourcing and there was a lot more data provided that you could go back to where it came from. But I

Dr Rupy: Or you take a little sample of it and it goes into like a little, you know, handheld.

Lara Lewington: Yeah, but the supermarket would have holes in all of their fruit and veg.

Dr Rupy: Or maybe one person could just do a batch and they're like, okay, this batch is really good. Don't go for that batch.

Lara Lewington: Yeah, well, yes, and I suppose the price would be relevant to that.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, yeah. Well, Abel & Cole, you told me about you just started an Abel & Cole subscription. So, you know, like an Abel & Cole could do the nutrient scanning for you. In the same way, because I'm very hot on independent lab testing, particularly for supplements, because there are a lot of contaminants that we find. And so good brands will actually be transparent about that batch's independent lab testing to be to show that it's free. Actually, Bryan Johnson does this on his website as well.

Lara Lewington: Yeah, he did it with some cocoa, didn't he?

Dr Rupy: Yeah, that's low in lead, low in cadmium that unfortunately is commonly found in dark chocolate or certain brands of dark chocolate because of the soil. So going that extra step, I think, you know, again, this is, you know, in the future and for people who can actually afford this, but I think going that extra step gives me a lot more clarity and a lot more trust that what I'm consuming isn't going to be putting me at harm down the line.

Lara Lewington: Yeah, especially people who've been dealing with chronic illness, post a cancer diagnosis, people who are really, really cautious about what they consume and want to really focus on diet.

Dr Rupy: Yeah. To move on to sleep, this is sort of like your special subject. Um, so what kind of things are there at the moment and what what do you think are future avenues for sleep to to optimise?

Lara Lewington: I actually think there's really mixed feelings about sleep tracking. And this is just anecdotal from people that I talk to. But one of the main reasons I wear a tracker, and I'm always wearing at least one tracker.

Dr Rupy: At least one.

Lara Lewington: At least one. I wear a smart ring all the time. By day, I also wear a smart watch. But that's actually mainly because I can do payment on it and until they bring it out in the smart ring, I'm going to be doing things like that.

Dr Rupy: Oh, so you use that for payments. Okay.

Lara Lewington: Yes, that's right. It's very easy when you're getting on the tube or bus, which in central London is a thing that I'm doing all the time. So I think the the idea of tracking sleep to me is incredibly important because I like to see how that pattern is going and have a bit of a better representation than how well I think I've slept. Now, that's not to say the sleep tracking is absolutely perfect. I think of all of the tracking, and I've done numerous experiments, again, non-scientific, just using these devices as anybody would, and the variation in sleep time and sleep staging is there a little. Now, Matthew Walker, professor who focuses on sleep at Berkeley in California, he's written a great book about sleep as well. I went to his lab and he showed me his sleep clinic, how it works there, that you have all of these wires attached to your head and you're monitored in this strange environment, which I think would put you off your sleep anyway, but he said you have a sort of night of adjustment. And he is, disclosure here, he is the sleep advisor for Oura Ring. He said that Oura is 75% of what the sleep clinic is in terms of sleep. Which actually, for something that you're wearing on your finger, is pretty good.

Dr Rupy: Pretty good, yeah.

Lara Lewington: And also, it will measure in the same way consistently. And I think this is something important about the trackers, that you don't want to keep swapping brands or comparing yourself with a friend using a different brand. Because even though these days in terms of activity, they are the differences are pretty negligible, heart rate seems to match up pretty well across the brands. You want to monitor you against yourself yesterday, you last week, and it allows you to be able to do that. So in tracking your sleep, I think even if the data is a little bit out, it's really useful to see that pattern and see how things have affected your sleep. If you've upped your caffeine intake and you know it's had an impact, and you see that in your sleep staging as well as how long you've been asleep, it might push you to reduce it. I've had a triple espresso this morning trying to overcome my jet lag. And I know it's too much. I need to get back to my double. So it it's really useful to be able to actually keep a long-term pattern of that. And one of the things that Matthew Walker said to me was that sleep pattern is seen to change 20 to 30 years before symptomatic dementia. So maybe one day we will reach a stage where it's not just about tracking your sleep, but using it as a potential diagnostic to raise the alarm bell that these changes are in keeping with those we see in people ahead of dementia, so you then go and investigate further. So in the longer term, I think there's real power as we collect more data, as we understand more correlations, and that's what's really exciting about this era of health care is that we are collecting uniform data built for purpose, collected for purpose to see how those correlations work in the longer term. We're collecting enormous amounts of data on huge swathes of populations in ways we've never been able to do through these devices. And sleep patterns, we're understanding a lot about what's going on all over the world. People in New Zealand are getting the best sleep, people in Japan are getting the poorest sleep. If you fall asleep at work in Japan, it's considered a mark of respect that you've been working hard. Do that in the UK, you'll get your P45. So there's really different attitudes to sleep, amounts of sleep, weekend lie-ins are a very European thing. And they're not necessarily good for us. We're better off to have a pattern where we're waking up at a similar time seven days a week. But you don't want to be deprived of sleep as a result of that. So these devices are allowing us to learn a lot about ourselves and a lot of population level. So for the people who may lose sleep over their lack of sleep, where this is really not a productive or good thing for them, well, they may gain something from population level understanding. This isn't for everyone and I think when it comes to anxiety over devices, sleep is probably the area that people may be the wariest. So for some, they might want to take their devices off at night time despite the power of being able to track.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, I think there's definitely a lot to be said for being more intuitive about your sleep needs and whether you're well rested or not. I mean, I personally use my ring, I've been using it for like eight years now, and it's given me a lot of, I mean, when my newborn was born, he's 15 months old now, I just remember looking at my average heart rate and it literally just skyrocketed after after he was born and like stayed like that for three months. It went up for like 15%, which is

Lara Lewington: Yeah, and that's the sleep deprivation you can't do anything about. For many people, there is sleep deprivation they can't do anything about.

Dr Rupy: That probably did compound my anxiety around sleep actually at the time because I was looking at the data, I was like, what can I do about this? Nothing.

Lara Lewington: Well, yes, when you know how bad for you it is to not get sleep, you're only going to feel worse about not getting it. And the devices will also encourage you as to when you should go to bed so that you are at the right point of your sleep cycle, at the point of the night which is best for you. I met a load of people in California setting their alarm clocks to go to bed at night rather than to get up in the morning to get sleep right. But it's a real luxury being able to do that.

Dr Rupy: I know, absolutely. Yeah. I remember it saying, oh, you should go to sleep now. I'm like, yeah, but he's crying. Well, it's like all the baby tracking stuff actually. Your baby needs feeding, your baby needs a nappy change. I think as parents, we know that.

Dr Rupy: You know that. You definitely know. I actually tried a tracking device on Raphael, my son. And uh, it lasted like a night and I just took it off straight away because like anytime he moved, the alarm would go off.

Lara Lewington: Was this one of the socks or one of the bands?

Dr Rupy: It was a sock. It was a sock. Yeah, yeah. I forget the name of the brand now, but I sent it back. It just it was not working for us because I thought it would be really interesting data for us, not not, you know, for any particular concern. I just thought it would be really interesting just to see like what his sleep waves are and whether we can actually monitor the sleep regressions and you know, because we had one at four months and um, I mean, generally he's he's been fine and we're very lucky and we're very sort of fastidious with his routine. Um, but it just it didn't work. And I was quite I was quite disappointed. I was quite looking forward to just getting some data on Raphael and

Lara Lewington: Yeah, well, I can imagine like we collect data on us. You've been wearing a smart ring for eight years. You clearly like data. And and you want it. But I've I've seen over the years a lot of different devices, even one that analyses a baby's cry to tell you what they are crying about.

Dr Rupy: Really?

Lara Lewington: Yeah. And it was based on the data of thousands of babies' cries. And the idea was that even though all of our babies sound different, there was some sort of way that it was trying to correlate. There's there's so much out there, but I know as a tired new parent, which was a long time ago for me because I've now got a teenager, but I know what it's like. You're you're exhausted, you're just trying to function. You don't want to be setting up a gadget as well alongside all of this.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, yeah, yeah. It's funny, isn't it? Because I think sometimes, I mean, I love tech and I love data, but I feel that it's taking us away from our traditional habits and our inner wisdom. I mean, I think I read this book called um, uh, Why French Kids Don't Throw Food.

Lara Lewington: I've read it. It's brilliant.

Dr Rupy: Have you read it? It's brilliant. I love this book. It's super funny. It's about this New Yorker woman who goes to live in France with her husband and she has a child and she's a sort of typical helicopter parent like I am, you know, always looking around and setting milestones and monitoring. And the French, generally, this is a big generalization, are a lot more laissez-faire and they go into like the natural way of their child. And you know, you can imagine by taking that approach, you naturally know what the different pitches are of cry that determine whether your child is hungry, your child has got a soiled nappy. Like that's the sort of inner wisdom that I feel sometimes tech is taking us away from.

Lara Lewington: Yeah, and the human instinct and the things that we want to do and we don't want to use tech for are equally important to recognise because the technology is there and created to try and help make our lives better and make things easier. But we've got to embrace the things we want to, the things that us as humans want. And that's actually something that I explore in the book as well that it's all very well what is possible, but just because AI can do something doesn't mean it should. And we want to embrace the things that work for us. There's still, there was there was this lady who I met in one of the world's blue zones in California. I went to Loma Linda and I met 103 year old Mildred.

Dr Rupy: 103 year old?

Lara Lewington: 103. And what was brilliant about going to meet her was this was the ultimate human story. I'd come from visiting Bryan Johnson in LA and going to see a whole load of scientists at universities across the US, the University of Southern California, Berkeley, Stanford. I had seen the absolute cutting edge of science. It was a programme about brain aging that I was doing. And then I went to Loma Linda and it just happened that in my filming schedule, it was at the end of the week. And I got there and I was welcomed by this wonderful lady who made me breakfast and welcomed me to the community. They're seventh day Adventists and for them, it's a duty of religiosity to look after their bodies. They are eating impeccably. I see what's on your shelves here. That's what they're having. Very similar. Really healthy eating. They all exercise, they prioritise sleep. There are literally lectures taking place for the community on healthy living. And I'd gone to first of all interview 99 year old Esther and I had to wait for her to finish at the gym. So I was there, there was a singing, a group singing activity taking place whilst I was waiting for her. And then there was a lift next to me. The doors opened, there was a sign in the lift that said only three walking frames at a time. And this really stuck with me because this community aren't magic, they're not superhuman. They're just aging better than your average Americans or average Brits. I'm saying America because I was in America. And they're living a healthier life for longer by what they're doing. But it's it's nothing wild and inexplicable. It's just slowing down the aging process a bit because they're living healthily. And then I went to to interview 103 year old Mildred. And the thing with Mildred was she'd had enough. She'd lost her daughter 30 years before. Her son was bed bound. And although she had no signs of disease and she was a sharp mind, every time she stood up, she was nervous that she was going to fall over. She didn't know who was going to come to her room to visit her next and she was within an assisted living facility where she knew lots of people and there was a real sense of warmth and community there. But it just went to show that this isn't everything. There's a really important human experience that goes beyond all of this. And it wasn't just a sense of community, it was also purpose. She'd had a very successful career. She was a doctor. She'd set up hospitals in Africa. She'd actually done a lot of important work over the years. And I just felt like she was she was feeling that that purpose was gone. And in her apartment all around, she's got all this memorabilia from her time in Africa. And it was really fascinating after a week of the cutting edge science, after going to see Bryan Johnson, just seeing what it really means to be human and what it feels like to be 103 because we talk a lot about longevity and staying healthy for longer, but we rarely talk to people in those sort of years of their life about how it is for them.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, yeah. I think that sense of purpose piece is super important and I think that gets sometimes gets lost in the technology conversation.

Lara Lewington: Yeah.

Dr Rupy: I think that technology can definitely harness that. I mean, I met my wife on Bumble, you know, so I

Lara Lewington: Well, of course, it holds incredible power.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, it's incredible. I mean, even, you know, like community events and padel, which is having a moment right now, has been for the last couple of years, you can book a court and meet some random people and play. So there's definitely ways in which we can harness technology to help us help with that that sense of purpose. But sometimes it can take us away. Um, like, you know, constantly obsessing over sleep data. Aside from wearables in that sleep space, are there any technologies that can actually just help us to get to sleep quicker? Um, outside of the supplement space. I mean, we were talking about melatonin before, right? Where, you know, the melatonin doses are huge in the states and we, you know, it's a prescription here.

Lara Lewington: We're talking 10 milligram pockets. And when you told me you would start somebody on a 0.25. Yeah. Because I'm breaking up those tens into tiny, tiny pieces trying to do the right amount because when I was using the time shifter app and you have this option, so you put in your flight details and I had a really crazy couple of weeks where I was a few days in New York, a few days in London, a few days in Sydney, straight back for an event in London 12 hours later. So I was determined to be as awake as I could be. And having put in my flight details and you answer the question as to whether you're going to take melatonin or not. And it was telling me to take one milligram. And I was thinking, oh, that's tiny with my 10 milligram tablets. But then you're saying even a quarter of that is what people would start on.

Dr Rupy: Time shifter app. I'm going to I need to download that. So that's the app that helps you get over jet lag or try and mitigate it.

Lara Lewington: Well, yes, it helps keep you in order, telling you when you need to prioritise daylight, when you can have caffeine, when you can nap. And when you've got a really fierce routine, but you need to be a good sleeper to be able to do it. That is one caveat to it. You need to be someone who can relatively sleep on demand. And I had a less successful trip with it recently, actually. I think the when you're only a couple of days in places, you actually you're not there for long enough to even adapt to the time zone. So in a way, it's probably easier than the nine days I've just spent in the US where I'm still struggling a week later.

Dr Rupy: Well, you're doing really well. But yeah, are there any devices that help you get to, I mean, thinking of um, uh, vagal nerve stimulation devices that are getting a bit more attention now within the scientific community. So just for the listeners, these are devices that you can either use transcutaneously, so you just put it on on the skin or on the over your neck. Um, but there are some other implantable devices that are actually being used. I believe one's just been approved by the FDA for use in rheumatoid arthritis as a pain suppressant. Um, so yeah, some of these devices, are there is there anything in that space that you come across?

Lara Lewington: Yeah, there are wearable devices. I remember one that you wear in the daytime for 20 minutes a day to help trigger the brain reaction that will help you sleep later. So it's almost like you're practicing it. But this wasn't something that I could actually test and tell you how I thought it worked because first of all, I sleep too well. But when I've tested sleep gadgets, and I've tested a load of them, and I didn't test that one, I actually got an insomniac, Dom Joly, the comedian.

Dr Rupy: Oh, really?

Lara Lewington: Um, to test a load of stuff. And I tested various wearables that there was one thing that was a headband, there was another that was earbuds that plays music to soothe you off to sleep and it tracks your heart rate. So the music is kind of in keeping with how your heart rate's dropping, um, as well as how you're going off to sleep. And so it soothes you off to sleep and then can wake you up in a soothing way. But the problem is, when I'm testing these devices, I'm so conscious of the fact I'm testing them, I sleep worse than normal because I'm worried, oh, it's come out my ear. I tested another one recently which was to track snoring and you have it stuck to your neck and it came out of a university, it's got proper scientific papers to back it up. But first of all, it didn't seem to stay stuck very well. And then I also thought, well, I need to be using another app to track my snoring because my husband just says I snore all the time. So there's it's actually quite difficult, I think, to to test anything that feels remotely scientific in how well these these work for somebody who sleeps pretty well. But a lot of these devices exist out there. And what can be done through vagus nerve stimulation, through obviously we've got a whole world of brain computer interfaces happening as well, which is absolutely fascinating. But what I did test recently that I can tell you had a real effect was a pair of headphones that through stimulating the vagus nerve and vestibular makes you feel like you're tipsy.

Dr Rupy: No way.

Lara Lewington: Now, the real purpose is for meditation, but it has a demo mode and I was at a health tech conference and I tried them on and we put them up really, really high. I had to grab hold of the man who was at the stand to avoid falling over. I don't drink alcohol, but I used to drink occasionally. So I know what it feels like to feel tipsy and I knew that's how I felt. But the weird thing is, the moment you switch it off, you feel normal again.

Dr Rupy: You're normal. No way. Immediately. Really?

Lara Lewington: Yeah.

Dr Rupy: What's the company called? Do you remember?

Lara Lewington: Uh, brain, oh, I'm trying to remember. Brain something. AI brain patch. Brain patch.

Dr Rupy: Brain patch. Okay.

Lara Lewington: Brain patch AI.

Dr Rupy: So it's meant to be helpful for

Lara Lewington: I'm not saying that's the proper answer. Brain patch AI. And then I took them on. I was doing my slot on Lorraine on ITV and I took them in to get Lorraine a little bit tipsy.

Dr Rupy: Really? On live TV?

Lara Lewington: Yes.

Dr Rupy: Did she feel tipsy?

Lara Lewington: She felt she did feel a bit funny.

Dr Rupy: That's hilarious. So it's meant to be good for meditation just to get you into flow.

Lara Lewington: Yeah, I mean, I posted this on my social media. I had a quarter of a million views. It's that was me just testing them at the at the show. But it was really, really interesting to see the effect it could actually have. I really felt that. There's another mode on it that gets you to walk, you try and walk in a straight line and you can't. You walk to the left or right. It just kind of controls you.

Dr Rupy: All from vagal nerve stimulation?

Lara Lewington: Yeah. It shows that they are doing something. And that's what's interesting about this demo mode, which isn't its real purpose, of course. But the idea of using it when lying down to do a bit of meditation alongside it, which at this tech conference I was at, I then got down on the floor and was trying, shows there's something there in the science. So these devices are existing, they are evolving, and I guess we will see how well they live up to the promise as they become more mainstream.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, that's amazing. I mean, in in that vein, is there anything around stress or anything to to help with stress? Because, you know, we're becoming a lot more stressed as a nation. Stress has a huge biological component as well. We know that stress can trigger inflammation, it can affect our gut. You know, actually going back to some of the stuff that we're talking about with regards to food and food intolerances, I think a lot of that can be psychological in origin. Not to say that it's all in people's heads, but the day-to-day stresses behind your computer, not moving, doing public speaking events, like all these things can trigger things within your your digestive tract that can be troublesome and people usually just look to food, but actually it can be, you know, stress related. Um, are there any elements around stress or

Lara Lewington: Yes, and different devices measure stress in different ways. And I almost feel like we haven't concluded yet which is the best way to do it. So you've got some wearables doing it through dampness on the skin. So assessing that as a sign of stress, others looking more towards heart rate and other factors. But there's also a company that I filmed with last year, Eli Health, that does saliva tests to monitor cortisol levels. And there's a few companies that were moving into that space. So, look, I would imagine in an ideal world, this is something you would do many times throughout each day. But obviously, in the interest of it being practical and this something not being too much of an interruption to our lives or people won't do it at all, the suggestion from the company is that you assign a couple of days a month to doing it and through those days you'll do three or four readings in a day. So you will see on the app your cortisol curve, which should be going up in the morning, going down later, and seeing how stressed you are from those readings. From everything that I've seen from stress tracking, that was something that particularly excited me. That company is all about hormone tracking. They're now moving into progesterone, they announced last year, they've just announced testosterone tracking. So through these same methods of their test strips, they're not hugely expensive, and you're

Dr Rupy: Is it like a blood glucose monitor? Like where you get the immediate result?

Lara Lewington: Uh, well, well, yes. So you do it with this with this testing strip that you put in your mouth, and then your phone scans the strip. There's a code on it and everything, and the results will, I think it may take 15 minutes, I can't remember. The results will come up on your phone, and then throughout the day, you'll have those readings from from four events, say.

Dr Rupy: Wow, because in my NHS days, we would only really do cortisol testing if we were suspicious of a cortisol producing tumour or another hormonal event. And and usually what we do is spit tests throughout the day. So we do four readings, one in the morning.

Lara Lewington: So that's exactly what this is doing. It's just bringing the ability to do it just in the home.

Dr Rupy: Wow. So which of these kinds of stress analysis is the thing that people really buy into long term and is proven to be really helpful is something that I think will gradually unfold because it is still very early for all of it. Albeit it's been a few years since our wearables have started to assess stress. And it can also, that can be quite stress inducing. When I look at my data from my smart ring and I see that it tells me that I've been, and it's normally very diplomatic. It'll use phrases.

Dr Rupy: I hate that. Yeah.

Lara Lewington: It'll use phrases that you're you're engaged, which I think is one level under very stressed. And so you see this data and you kind of think, what was I doing at that point of the day? What was causing it? I used to have on my smart watch a function on where it would actually give me an alert and it would tell me to breathe. And the weird thing was, I would realise when it said it that I was sort of, I was slightly holding my breath. I was either deeply in thought or in the middle of doing something. But look, some some stress, there's a difference between acute and chronic stress, of course. And acute stress when we exercise or whatever is not bad in the way that chronic stress is. So this sort of analysis also takes a lot of understanding of the readings. And I think with all of this technology that we're using, we need to understand what that means for us and how relevant it is and what to not take notice of as well as what we should recognise as potentially a problem.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, I agree. I think with all of these devices, the interpretation of the data is key because someone could look at a high cortisol level, um, for example, as being a negative thing or like, you know, a suggestion that you are stressed as a negative thing. But like you said, there's good stress, there's bad stress, there's how we respond. There are certain people that actually thrive under that stress pressure. I know anecdotally from the sort of stress graph that I've got on my wearable, I can actually see when I'm off or on holiday, my stress levels are actually really low.

Lara Lewington: Wow.

Dr Rupy: And so it always says, you know, you're relaxed or whatever, like, you know, you're almost

Lara Lewington: It's good you're not getting stressed by a 15 month old.

Dr Rupy: Yeah. There are peaks around feeding time. But, you know, on days where I'm working, the stress is high, but I don't see that as a negative thing. I think it's more that I'm engaged. You know, that

Lara Lewington: I was about to say that, the exact word engaged. Maybe there is some reality in it.

Dr Rupy: I think so. I think, you know, without stress, you just you couldn't engage. You need stress. You need those stress hormones. They're very, very useful. But I think it's like it should be pulsed through the day. It shouldn't just be constant. It should be, you know, periods of rest and downtime, which is why I think taking breaks and all that kind of stuff. I think if if people could be nudged in that direction using some of these wearable devices, then it makes sense. But again, I think it's user dependent on all this stuff.

Lara Lewington: Yeah, and I think

Dr Rupy: That's really interesting about Eli Health. I haven't heard of Eli Health before.

Lara Lewington: It's I think they're Eli. E L I.

Dr Rupy: Eli. Okay. Eli.

Lara Lewington: And I think when we when we look at the longer term as well with a lot of this and even continuous glucose monitors, we're starting to see devices emerge that aren't directly tracking the thing that they're looking at. So a continuous glucose monitor has this micro needle that's going into your arm. Well, there are also devices that are watches that are making the correlations using their algorithms between other vital signs and what readings that normally indicates. So this does mean that in the longer term, our wearables are likely to predict a lot of other data points, to be looking at far more biomarkers than they are now, things that may seem very difficult to do in unintrusive ways. So I wonder how that will play out for stress because it will be able to bring in more factors and maybe a greater understanding also of what the good stress is. You push your body really hard in that spin class this morning and something that seems more like a longer term concerning stress because we're already starting to get this feedback in written information to us telling us a little bit more about the readings that they're finding and what it might mean. And the apps have evolved so much in terms of that, actually describing to us what's going on and what changes we might want to make.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, that's the AI bit, isn't it?

Lara Lewington: Well, one of the smart rings, I did an experiment of lots of the smart rings at once recently. And one of them had a large language model built into the app so you could use it as a chatbot.

Dr Rupy: Oh, nice.

Lara Lewington: And the speaking out loud to it, unfortunately, had some glitches. That wasn't really working, but you could type and you could ask questions about, is the night that I slept the best last week the same as the day I did the most exercise?

Dr Rupy: Oh, interesting.

Lara Lewington: So you can maybe have those interactions. And I guess we're heading towards that probably eventually becoming the norm for all of it because it's not wildly out there technology based on what we have right now. It's perfectly plausible.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, for sure. It's like having an Apple health kit, but you know, connected to chat GPT or Grok or whatever. Um, great. That's that's epic. Um, let's bring it to activity then. I guess in terms of activity, a lot of these wearables are sort of like built for that with the advent of Fitbit and and Garmin and and you know, apps that connect with those like Strava. But you mentioned right at the start of this pod, if exercise could be condensed into a pill, it would be literally like the blockbuster bug, drug of um, well, of forever really, because of the benefits of exercise that are just so well recognized by everyone. But is there anything aside from wearables that encourage us to be more active out there that can mimic the effects of of exercise?

Lara Lewington: I think we all need to get moving as much as as much as we can. And the difference between doing nothing and doing something is huge. And so encouraging people to make those steps forward, no pun intended, um, is really important. The 10,000 steps that our wearables are telling us to do is a fairly arbitrary number. It was actually born out of a marketing campaign for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. It's not exact science that we need to do 10,000 steps, albeit it is good for us. So it's somewhere around the 7,000 that a lot of the research is based on. There's even research for some older women based on around the 4,000 mark on the difference that it makes for various different health conditions. And we also know that doing different types of exercise is important. What cardio does for you is different to what weight training does for you, and you also should be stretching to keep supple. But obviously, all of this is just giving people another list of things that they need to do. So I guess a priority here is not overwhelming people with you must do this and something really extreme and they end up doing nothing. It's doing what works for them and habits and consistently doing it. So an activity tracker does help nudge people into doing it more. And the time that I really saw this was back in, it was around 2015, so it was fairly early days for activity trackers. And I'd done an experiment with four of the leading brands at the time. And I had these big clunky watches on doing it. And it was summertime, so they were showing. And people kept on asking me what I was up to. And actually the results back then, huge discrepancy between what they were reading, a 25% difference in the number of steps that one thought I'd done compared to another. One thought I'd burnt 3,000 more calories in a week than another, and that wasn't the one that thought I'd done all the steps. So these differences were massive. And if you were trying to match up what you were eating to it, this this was not great. And when I spoke to one of the CEOs of one of these big companies, he said to me, well, at least it's consistently inconsistent. So you can measure you against yourself last week, just don't measure yourself on another device. And it was the greatest PR spin I've ever heard.

Dr Rupy: That's a great PR spin.