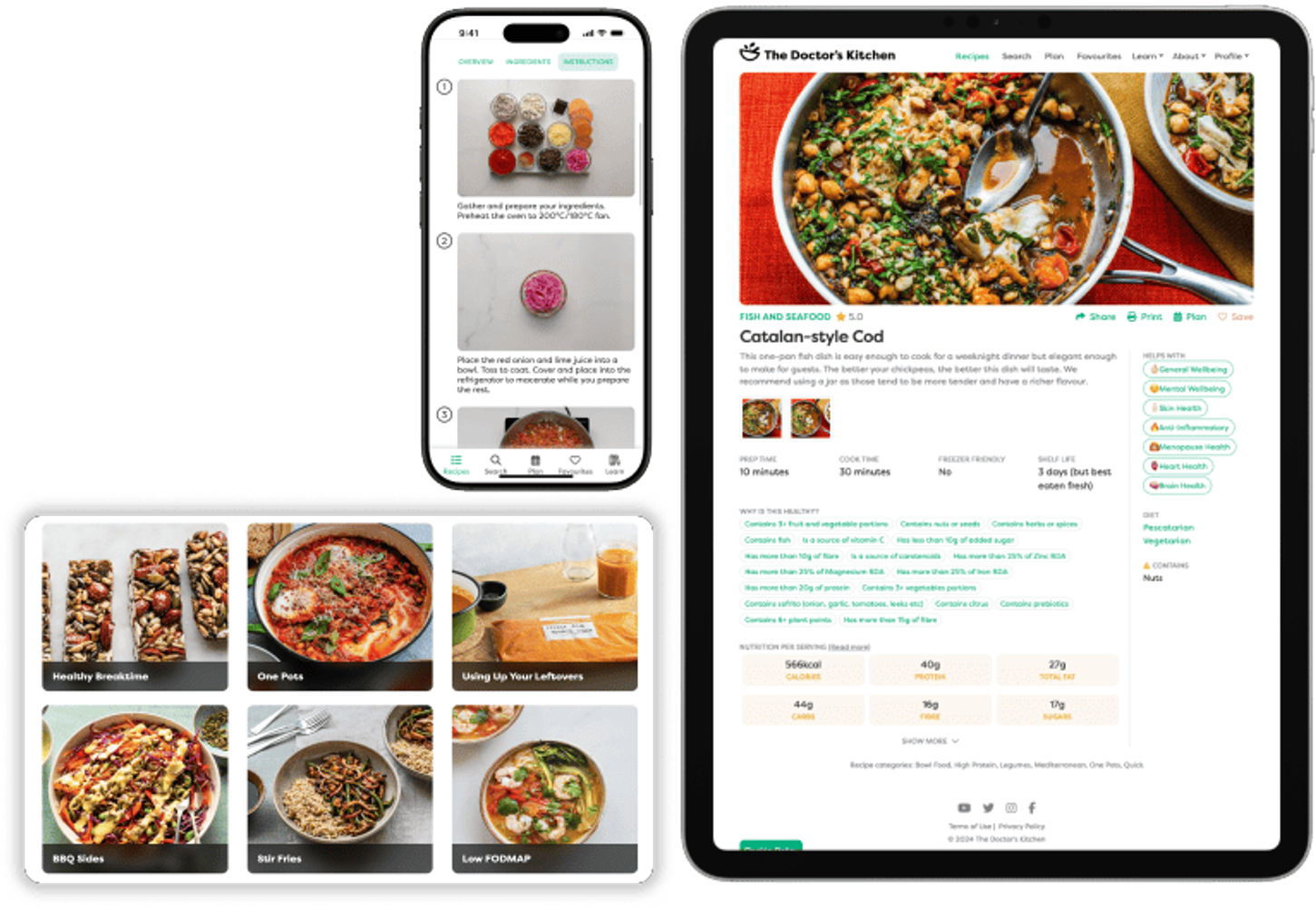

Dr Rupy: We've long been told that health starts in the gut, but what if the key to ageing well actually begins in your muscles? That's what we're going to be chatting about on today's episode of The Doctor's Kitchen. This week I'm joined by Dr Gabrielle Lion. She's a physician and author of Forever Strong and founder of the muscle-centric medicine movement. Gabrielle's work reframes how we think about muscle, not just for strength or aesthetics, but as a powerful metabolic and endocrine organ that drives longevity, energy and resilience. And in this episode, we discuss why muscle is the foundation for metabolic health, how much protein you really need and how to get it right, how good muscle health impacts inflammation, brain function, vascular function, and the mindset shifts that we need to use to make new habits actually stick and why we should be thinking about standards rather than goals. So whether you're in your 30s trying to stay active or in your 60s building strength for life, Gabrielle is going to get you pumped about getting pumped. After recording the podcast, I just wanted to run to the gym and start working out with those kettlebells. She's just so enthusiastic and so motivating. And if you want a bit more from Dr Lion, you can check out the Forever Strong playbook. That's her new book that released on the 27th of January in 26. Something else I'm obviously passionate about is ensuring that you have a high protein, high fibre, anti-inflammatory meal for breakfast, lunch and dinner. And that's exactly why I started The Doctor's Kitchen app. It gives you endless variety, over a thousand recipes plus virtual Dr Rupy that will help you with ingredient swaps if you don't have oats or you're allergic to tahini and sesame or you don't like a particular ingredient like tofu, it will, he or it, I don't know how to refer to my own avatar at the moment, but will give you recommendations and swaps depending on what you need and whatever your purposes are. Honestly, go check it out. You can try it for free on the App Store or on the doctorskitchen.com website and it's been game changing for a lot of you. Now, on to my podcast with the wonderful Dr Lion.

Dr Rupy: The Forever Strong playbook. Let's talk about why you wrote this because you've written extensively about muscle-centric medicine before. What was the missing piece of the puzzle that even encouraged you to write to write this?

Dr Gabrielle Lion: Well, it's funny. After over 15 years in medical practice, you put together a body of work that is scientific, but let's face it, that can be really dense for people. And this book is the book that I wanted. I wrote the book that I wanted and it is protocol-based. It highlights the science, it has pictures, it has recipes, it has workouts, protocols. So I could just flip to a page and it has anything and everything that I personally could want and it's based out in pillars. How to think, how to move, how to eat, how to recover. And you know, from my perspective, it's one thing to have a body of work that is dense and people have to read and then it's another to have a playbook. It's not a workbook, it's a playbook. It is the tactical field guide that you could take with you to the gym or take with you to the kitchen. And frankly, it turned out exactly how I wanted it to, which is very unusual for an author to be able to put out into the world something that they really wanted.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, yeah, yeah. No, I hear you. I mean, when I wrote Healthy High Protein, for me, that was like for me because I was struggling to hit my protein needs and my fibre requirements and the plant diversity and all that kind of stuff. So it's always magical as an author when you actually utilise your own body of work. So that way you know you're actually really speaking from personal experience and you're putting out something that you're genuinely happy about and you're you're genuinely and you were just telling me before, you know, you don't you don't sort of pat yourself on the back when you write books and you put stuff out there. So the fact that you are, it's great. Well, let's take a step back and talk about muscle-centric medicine and just remind folks what we mean by muscle-centric medicine and why this is so important.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: My favourite topic, which is muscle. That and my kids, I would say. And muscle-centric medicine is this concept that muscle is the largest organ system in the body. And why does that matter? Well, right now, the common theme is that muscle is good for strength and power and athletic performance, but it is such an underappreciated organ system as it relates to our metabolic control centre, as it relates to our interface with dietary components, meaning if we are mismatching our nutrition for muscle health, then we're going to suffer with all of the issues of chronic disease. It's not an obesity problem per se, it really is a muscle problem. And then another component of muscle, and we're really talking about muscle-centric medicine, is that it is the only organ system that we have full voluntary control over. It's the only organ system, which means twofold. Number one, it is a choice. It is a choice for strength, power, mobility. It is also a choice for this bidirectional relationship between physical and mental strength. And all of this encompasses muscle-centric medicine and muscle as this endocrine organ as this focal point.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, yeah, yeah. You mentioned a couple of words there that I want to clarify for the listener. So when we talk about metabolism, how do you describe metabolism to your patients and how do you describe it to your audiences?

Dr Gabrielle Lion: Well, I'm going to describe it at the way I think about it as a scientist, and then I'm going to describe it the the common way that we think about it. So as a scientist, the way I think about metabolism, metabolism is this these chemical reactions within the body and how I think about it from a health perspective is this. Is that organ system doing and burning what it should without any kind of derangement? Meaning, for example, skeletal muscle that makes up 40% of our body weight is designed to burn fatty acids at rest. From a metabolic chemical perspective, it's supposed to burn fatty acids at rest. Carbohydrates, if we overconsume carbohydrates, we can distort our metabolism to force muscle to burn carbohydrates at rest. So this is now a distorted metabolism. So your overall question is how do I think about metabolism? I think about all the chemical processes in the body. However, for me, as a nutritional scientist, I think about, is this organ system, primarily muscle, burning what it should? And are we providing a diet that allows us to be healthy overall? Or are we distorting our quote metabolism by overfeeding and mismatching our muscle health with our nutritional health?

Dr Rupy: So putting it in lay person's terms, when I think about this, what you're saying is we should be burning fat primarily when we're just sat here, like right now we should be burning fat, but because of the modern era in which we live in, because there is an overabundance of food in general, but particularly those coming from carbohydrates, including refined carbohydrates primarily, we are sat here and instead of burning fat, we're actually burning carbohydrates for energy where it should be the other way around.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: That's that's exactly right. And that creates a lot of problems down the line. We should be burning fatty acids at rest. We want muscle to burn what it is quote supposed to as opposed to deranging it and forcing it because it has to get rid of glucose instead of forcing it to utilise glucose. So how we use glucose, so at rest, you know, as we begin to ramp up, there's kind of this crossover. At rest, it's burning fatty acids and then as we begin to ramp up into more activity, we use more carbohydrates and that makes sense. And you know, when we think about how do we design a healthy diet, there are two ways to think about it. There is one way to think about designing a healthy diet if someone is sedentary. How do we think about and just by numbers, I mean your listenership might not be, but frankly, just by numbers, we know that the majority of individuals, our parents perhaps, are sedentary. And then of course, there's the more active individuals and then we can design a diet which they have a lot more flexibility because they have a lot more muscle health, right? Their muscle looks like a fillet rather than a ribeye. And you know, if scientists listen to this, there's a little bit of nuance there, but overarching, we could say that healthy muscle looks like a fillet. And individuals that are training are able to utilise more carbohydrates. And that's how we have to think about metabolism and not as, you know, because someone could say, okay, well, where does this happen? It happens within the mitochondria. All of that is true. But if we were to say what can we take from action steps. So I've listened to your podcast, I've listened to many of your podcasts. You did a great one with Kevin Mackey, just fantastic. He's extraordinary. And you asked questions that provided the listener or the viewer to take action. So should they eat red meat or not? Is it healthy for someone with LDL cholesterol or not? You know, there's there were questions that allowed for a meaningful influence for the person's life. And I would say we can talk about metabolism, yes, and we can talk about what makes it healthy and what do we need to do so that we can maintain our blood glucose levels, we can maintain our insulin, we can maintain triglycerides, that kind of thing. That was a very long-winded answer, but I think it was a great question.

Dr Rupy: No, no, no. It's it's it's all good. I I I definitely see that side of it. And I think from the listener's perspective, it's like they they want a strategy. It's like, okay, fine, we should be burning more fat. I might not be burning more fat because of two main levers that I'm not pulling. I'm either not moving enough, or I need to shift my diet. So my flexibility, my metabolic flexibility is shifting away from burning carbohydrates to primarily burning fat, which is, let's face it, what the majority of us should be and want to be burning as our primarily primary fuel source. So if people are listening to this like, okay, well how do I get into that fat burning mode? This is where, you know, muscle-centric medicine kind of comes into itself, right?

Dr Gabrielle Lion: Yes, yes. And when we think about muscle and we think about muscle health, this is very underappreciated, is muscle is not very metabolically active. Right? So it might be 15% of resting energy expenditure. It might be 15% because of the amount of mass that we have. But you know, the other organ systems like the brain and the other organs are more metabolically active. And people will say, I need to put on more muscle because I need to burn more calories. And that's not exactly correct. You need to put on more muscle for a number of things, but burning calories frankly is not one of them. You know, when you think about how we dispose of and utilise carbohydrates. Let's take carbs for example. Because I think that this is a misconception. People will say, again, I'm putting on more muscle because I'm going to burn more fuel. It's not that metabolically active. Where it becomes important is it is your body armour if you are ageing. It is your amino acid reserve. There's a lot of reasons why we want more muscle, but calorie burning is not one of them. And I just think that that is important if we are thinking about how do we reorient ourselves to what muscle does and why it's important. And really, when it comes to take home messages, how do they design a diet? You know, my first book, by the way, I I talked all about calories and it was a little more complicated. In this book, I'm probably not even supposed to be showing you these pictures, but I'm going to I'm going to show it to you. We made it so that it was more of a plate model. And for those that can see it visually, we we designed for someone who doesn't want to count calories and how you portion your nutrition. And basically, the first decision you make is how much protein you're supposed to have. The first decision. And that's based on a few things. It's based on age, it's based on activity level, it's based on metabolic health, and then finally, it's based on personal choice. The older you are, and I am embarrassed to say this, but above 35, we are considered more mature, which is funny, right? You're thinking like 35 is so young, which it is, but the older you get, so 35 and up, you know, as you move into your 60s, you need more calories from protein, you need more protein, not less. And I'll pause there because I'm sure you have questions and again, from a practical perspective, what can people take away?

Dr Rupy: Yeah, yeah, yeah. I mean, the obvious question comes to mind is how much protein should we be consuming? And I know that you're going to add the pragmatic perspective to this because there's what certain people look at in terms of the science and the epidemiological studies, but then there's also what a practicing physician knows what actually works in the real world. So I'd love for you to talk about how you parlay those two.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: Well, certainly. And I'll say this, I was actually trained in nutritional sciences and also mentored and I'm still mentored by one of the world-leading experts in protein metabolism. And he is a research scientist. His name is Dr. Donald Layman. He'd be a fantastic guest. And you know, he's taught me everything that I know. And when we think about dietary protein, let's first think about what it is. We talk about protein as if it's one thing. It is not. It is a handful of amino acids, some of which are essential, meaning the body cannot make them. They must get them from the diet and the other are non-essential, meaning that we can regenerate, recycle, we can make them. So as we think about protein and we think about these essential amino acids, leucine, isoleucine, threonine, phenylalanine, they all have unique biological properties. They're not interchangeable. For example, when it comes to muscle health, the main amino acid that we talk about is called leucine. And this is necessary to stimulate muscle protein synthesis, which is a proxy of muscle health, which, by the way, this process decreases its efficiency as we get older or if we're sedentary. The other amino acids, for example, threonine. And so you and I were talking before you before we hit record that you just interviewed one of your best friends from medical school who's a gastroenterologist and you were talking all about constipation. Threonine is an essential amino acid that's primary role is to make mucin in the gut. Leucine and threonine are not interchangeable. And so we begin to, while it's impossible to think about dietary protein specifically, how much do I need for each level of functioning because that would be a bazillion things. You know, what do I need for neurotransmitter, neurotransmitters? How much phenylalanine do I need or how much threonine do I need for mucin production? Just conceptually understanding that all proteins really are not created equal because it's based on these essential amino acids which do various things. So that's great. And then the next question is we understand that they all do various biological roles, but if we begin to think about overarching, why we need protein, I can think of a few big picture things. Number one, protein turnover. And protein turnover is not just muscle, it's all enzymatic, structural and functional components of the body. Our body does this around turns over completely, a new body, hopefully one with less wrinkles, at least for me, four times a year. Four times a year. Now imagine the efficiency of this decreases. So the ability to do this well decreases. We might see this in part with skin ageing. Again, there's a natural component to say like sun damage or ageing, but the efficiency, maybe our hair changes, maybe the texture of our skin changes, maybe we're not able to heal as fast or maybe our immune system is decreasing a bit. We find that we're getting sick more. So the the efficiency of these body processes decrease. And one way to offset this decrease in protein turnover, this repair rebuild process, is to ensure that we have the baseline building blocks to support this process as we age. Therefore, from a muscle-centric perspective, which again makes up 40% of the body, this is my primary target. And when you eat for muscle health, all of the other essential amino acids fall into place. You get enough threonine, you get enough phenylalanine, you get enough valine, you get enough of all of these essential amino acids when you shoot for muscle health.

Dr Rupy: And so when we start thinking about the quantity side of things, what what are we what are we aiming for and how do you contextualise that to different age groups? Is there a difference between sexes, etc?

Dr Gabrielle Lion: Well, the first way, I'm going to I'm going to tell them exactly, I'm going to tell you guys exactly the amount and then we're going to break it down so that you can choose. Now, anywhere from 0.7, which someone could be 0.7 per grams per kg. I wish I had my phone, I would calculate it out for you. Oh, I do. So 0.7 to 1 gram per pound of ideal body weight or target, I should say, target body weight. So for example, if someone is 150 pounds, which is, let's see, 2.2 kilos, would that be 68 kilos? Yeah. Okay, so 68. So if someone is 60, roughly 68 kilos, then at the high end, you would be looking at 68 kilos is 68 times 2.2 is 100, around 150 grams of protein would be at the high end. So 68 kilos, so it's around 1 gram per pound or 2.2 grams per kg.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, got you. Okay.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: Now that's at the high end. At the lowest end, we don't recommend anybody eating less than 100 grams of protein a day. Because when you go below 100 grams of protein, it seems as if protein doesn't have that same biological effect that we want it to have. For example, you know, when you're able to dose protein effectively, which is how much protein you have per meal, we recommend anywhere between at the low end, 35 grams up to 55 grams. When you bolus protein at this, it starts this machinery that is energy expensive because it affects muscle. It allows and it promotes muscle protein synthesis. But below that number, it doesn't turn on the machinery. And that is important and interesting to understand that there is this dosing component to how we think about muscle health. So at a high level, the total amount of protein per day matters most, if we were to put this in a hierarchy, and it could be anywhere from 0.7 to 1 gram per pound. You're going to have to my friend calculate that to 2 kgs. And the evidence, if we were to go back and we were to look at the evidence, we know that 0.8 grams per kg is too low. So this is how we've set it right now. Yeah. And then typically everything above 0.8 grams closer to 1.2 grams per kg, people always do better. They do better from a weight management standpoint, they do better from a maintaining lean mass. So lean mass is not just muscle, it's all the other organ systems, maintaining lean mass. We also see that at the higher end when carbohydrates are restricted, meaning, you know, you're not talking about going above 130 grams of carbs unless you are doing activity, then we see a decrease in fasting blood sugar, a decrease in triglycerides, we see an improvement in body composition, we see a whole host of other things that have that are meaningful outcomes. And the more protein you eat, if you're closer to 1 gram per pound or 2.2 grams per kg, the less it matters if it's plant or animal from a protein perspective. However, you still have a micronutrient need. B12, B6, iron, selenium, you have all of these nutrients that ride along with high quality proteins. Whereas plant proteins, we think about in terms of fibre and phytochemicals, all of these other things. And that the best of both worlds is probably a protein focused, high quality protein plan with copious amounts of fibres and fruits and vegetables.

Dr Rupy: Yeah. Okay. So what I'm hearing is aim for over 100 grams as a minimum for everyone. Opt for over 1.2 grams per kilogram of body weight. Try and get a good mixture of different proteins. You're going to get the phytonutrients and fibre from plant-based and you're going to have to supplement or you can go for meat and I'm assuming lean meat, red meat, there's lots of different options, fish, and you're going to get the full suite of these different amino acids in good quantities. And as long as you're not over consuming in terms of energy from calories, going up to that 2 grams per kilogram may also give some incremental benefits as well.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: Yes. And I will say this, this is the thing that everybody does, everybody eats. We have to get this right, especially from a muscle health perspective, because building and maintaining muscle gets more challenging as we age. There are the two main fibre types that end up changing. There's type one, type two fibre types. And there is this transition from type two fibre types, which are the bigger, bulkier muscles that we think about when someone is weightlifting, to these type one fibres, which yes, are considered important for mitochondrial health and they're, you know, you think about endurance and runners, but what we also see is that this transition from type two to type one, people lose power. They lose the ability to move quickly and with force and strength. And we know and we see people, just cognitively, we see these ageing transitions. And so we have to recognise that number one, you have to get a nutrition that supports muscle health right. And number two, it's a non-negotiable to be able to provide enough stimulus. You know, people talk about progressive overload. That's not exactly correct. It really is progressive stimulus. And the reason I I say this is because I think in the landscape right now, and I'm a trained geriatrician. I don't know if you know that. So I I'm a trained geriatrician, meaning I specialise, I did my fellowship training in people 65 and up. And one of the things that we always test is we test these physical markers to make sure that people's power is maintained and it was a sit and stand test. You know, you count how many times can people do from sitting to standing in a period of time, walking speed, all of these grip strength, these are components that are biomarkers by proxy for overall health. And we also know that the stronger an individual is, the more likely they will live longer. The stronger an individual is, the more healthy muscle mass they have, the greater their survivability. And I'll also say one more thing, we just published a paper in sexual reviews and it is the relationship between sexual function and muscle mass.

Dr Rupy: Oh, really? And so and the two go hand in hand?

Dr Gabrielle Lion: They go hand in hand. So this was the paper is exploring the link between muscle quality and erectile dysfunction, assessing the impact of mass and strength. And so basically, we looked at a bunch of data and it what we found was that skeletal muscle mass and strength contributed independently to healthy sexual function through metabolic and endothelial mechanisms, particularly in ageing. So I I think that this is important and this is just one example of why muscle mass is so critical and it really is the focal point for all of health and wellness. Think about it, the more muscle mass we have from an endothelial function, exercise improves endothelial health. When I think about exercise, I think about it in various buckets. I think number one, strength, power, mass, right? The the normal bodybuilder, whatever it is, be jacked and tan, wear a skinny tank top and go to Venice Beach. I think about it from the second perspective, which is what about mitochondrial health and metabolic health. So this is kind of that dietary component. And then I also think about pulling the lever of muscle for plumbing and endothelial health, for vascular health. It's very well established in cardiovascular health, less established in sexual function, but the information is there and again, we just published this paper. This is just another reason to understand that because we have voluntary control over this tissue, that we really have to maintain its strength, but the process of getting strong and it's not just strength, you know, there is again, endurance, there's the plumbing aspect, which is either zone two cardio or high intensity interval, you pick it, you do have to have a good cardiovascular base, which also in all honesty, I don't have a great one. I used to, but with time constraints, I go to one conditioning day a week. I need more. And also my husband is crazy. He's running a 50 mile run next weekend. He just decided to do it. He thinks I should come cheer him on. But I I say this all joking that I think people gravitate towards one movement or the other, but neither one are a replacement for the other, especially when you think about those three buckets.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, yeah. I I what I'm hearing is that you really need that variety. And I love the way you put that together, you know, the strength, power, mass, mitochondrial health, vascular health. And you know, erectile function for men is almost like the canary in the coal mine, right? So if you've got poor erectile function, poor sexual health, then it's usually a marker of poor vascular health more generally. So you would expect that, I mean, the hypothesis would be if you improve muscle mass and you improve your cardiovascular training, then it would, it would have that knock on effect as well.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: Well, think about this. You're absolutely correct. And 40% of men by age 40 will have erectile dysfunction.

Dr Rupy: 40%?

Dr Gabrielle Lion: 50% of men, and you know, you're so here's why this matters. Whether your listenership is male or female, sexual health is a partnership. 40% of men will have erectile dysfunction by 40. 50% of men by age 50. And if we believe in this relationship between muscle mass and strength and sexual function, and now we layer on the use of GLP-1s, we are going to see an epidemic of not only sarcopenia, but I would argue that we are going to also see a decline in vascular health, which is going to also then therefore by proxy, again, I'm making a correlation here, but seems reasonable because we know that sarcopenic men have more erectile dysfunction. I was looking at one study, it was 73% versus 40 some percent. That's a lot that now if we don't take care of our our muscular health, it's not just about vanity, it will affect sexual function. And you know, frankly, that's terrifying for people.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, yeah, yeah. I want to get into some of the concepts in your book around the thinking process and the self-identity piece because I think that's really, really important. But just before we go on to that, I want to just double down on the biomarkers piece. So you mentioned a couple of biomarkers that you've used as a geriatrician. What biomarkers, if not those, would you be thinking about at different age groups to ensure that our muscles and our muscle-centric medicine with our muscle-centric medicine hats on, like are things that we should be doing regularly, like either yearly or at least every couple of years just to make sure that we're we're on the right track?

Dr Gabrielle Lion: So this is going to surprise you, especially because being a physician yourself, we have been taught about metabolic syndrome. A long time ago it was called syndrome X. And for you guys listening, it is high blood pressure, body fat percentage above 30, elevated levels of triglycerides, elevated levels of insulin and elevated levels of glucose. We were taught in medical school and residency that this is a symptom of obesity. Were we not?

Dr Rupy: Yeah.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: Okay. This is not a symptom of obesity. This is a symptom of unhealthy muscle first. The clinical signs that your muscle is metabolically unhealthy are the same signs for metabolic syndrome, formerly known as syndrome X. Because you and I discussed that at baseline, muscle is supposed to burn fatty acids. When your carbohydrate intake is too high, and by the way, we looked at this in studies. So when we reduced carbohydrates to 130 grams or less, we saw a 20% decrease in triglycerides across the board. One way that we assured people were following their nutrition plan is that we would look at their triglyceride levels. The primary site for glucose disposal, by the way, is skeletal muscle. To dispose of glucose and also burns fatty acids at rest. If we are over consuming carbohydrates, it has to get repackaged and it has to go somewhere. So, also, elevated levels of glucose, the primary site for disposal is muscle. Elevated levels of insulin, if skeletal muscle, which makes up 40% of our body, is insulin resistant, then and also sedentary, one way that you can use less insulin is if you are exercising, you do not need insulin to move glucose into the cell. It's a different transporter. Right? So it's it's not using the same transporter that insulin would use. You don't require insulin to utilise glucose if you are moving, which is this idea of going for a walk after a meal, do pushups, do air squats, you have to move your body. Super simple, easy. If you had a blood glucose monitor, you could see in real time the effectiveness of your skeletal muscle.

Dr Rupy: I mean, it makes total sense now, like the way you you you put it like that because, you know, people listening to this are like, oh, I thought metabolic syndrome and, you know, the the different markers that my doctor does is uh a a looking at my risk of type two diabetes, my overall metabolic health. And it is, but when you break it down, you look at, I mean, we talked about this last time, but just to refresh in the listeners's mind, muscle is a primary site of glucose disposal. It is where we burn our fatty acids. It is active as well as passive transport of glucose. So all these different things would be reflected in a poor metabolic picture if your muscles aren't doing their job. So high triglycerides, high fasting glucose, high fasting insulin, all these different sort of markers. So I love how I love that. Like because these are all very accessible tests that you can get done by your NHS GP and should be getting done regularly as a marker of overall health and it's actually a reflection of your muscular health.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: And there's and there's one more thing that I think is really important because people can be extremely discouraged because it's hard, right? So when an individual suffers from obesity, it's not an easy thing. And I will say that skeletal muscle health and for the longest time, so I was wrong. For the longest time, I thought that body fat percentage was the thing. I thought that this was the primary challenge for people. But the more that I learn and the more that I talk to these world-class experts, I realised and I'll never forget, the aha moment for me was when I was actually interviewing the world-leading expert in PCOS. Her name is Dr. Melanie Cree. She's an MD PhD. She has done out of the eight trials in with GLP-1s and fertility, she's done two. She's the world-leading expert. And she was sitting across from me and I was like, Melanie, I I just I really need to understand this from my perspective. What percent body fat is the number that is going to affect fertility? That makes it more difficult. Is it 30% body fat and then after that, it's a challenge? Is it like what is it? She looked at me and again, you know, you and I, we we have these aha moments when we're in conversation because we grow together. And she looked at me and she goes, Gabrielle, body fat percentage is irrelevant. I'm like, what are you talking about? She said, no, it's the infiltration, it's the intermuscular adipose tissue. It's actually the fat in skeletal muscle that is the biggest driver of insulin resistance, of derangement in metabolism, of all of these things. And I was like, well, I don't understand. How come we're just focusing on body fat percentage? She goes, well, frankly, you know, I'm I'm looking at intermuscular adipose tissue under ultrasound and MRI. I'm like, oh yeah, that's totally inefficient and at a population level, number one, MRIs are a total pain. And number two, ultrasound variability, you and I both know, it's it's very difficult. You're not going to ultrasound your whole body and maybe let's say you do vastus lateralis, people distribute body fat differently. Again, it's not about body fat, but I imagine that the intermuscular adipose tissue distributes differently. So at the end of the day, and she said, no, Gabrielle, she goes, it's very empowering because whether someone is losing a percentage of body fat, the simple fact that they are out there training and exercising decreases the intermuscular adipose tissue.

Dr Rupy: Got you. Yeah. Yeah, yeah.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: And um, you know, I just think it's very empowering. People are listening to this and they're like, okay, so I have to eat more protein. We should, you and I should talk a little bit about how we dose carbohydrates. And then they go, okay, well, I have to exercise, but my body composition isn't changing. I feel very disempowered. And my statement would be, the fact that you are moving, you are getting healthier. You are improving muscle quality and function simply by moving rather than focusing on body fat percentage of what you have to lose.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, yeah, totally. I I completely agree. I and I I understand the difficulties as well of trying to determine that as a biomarker that's accessible at a population level because, you know, ultrasonography, depending on where you do it, we distribute fat differently. It's also operator dependent as well, like whether they're able to pick up on that, how do you actually estimate the fat percentage in the muscle that you're looking at. I wonder if there is concordance between body fat percentage and and muscle fat, right?

Dr Gabrielle Lion: There is, but they're also independent.

Dr Rupy: Got you.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: You know, it seems to be that some people that have more body fat percentage will have more intermuscular adipose tissue, but it's not always that way. Think about the lineman. So remember there was this whole thing about um metabolically, I I don't remember exactly what they it was basically and and forgive me if this comes across wrong and I mean no disrespect, but it's the fit and fat, you know, there was this whole thing. Um and that's and for the longest time I'm like, no, that that can't be right. There's something happening. And and I was wrong. And the and the reason is is that it's this flux. So when we are not creating flux in our muscles, we are distorting the muscle quality. You get ceramides and diacylglycerol, all of these byproducts build up in this tissue. So as you can imagine, if you think about it, you think about a marbled ribeye steak or you think about tissue that's just really been sedentary and that's kind of gross, but you understand what I'm saying and um but it's it's this decrease in flux. How about this? Think about a pond. A pond that doesn't move, it gets very stagnant, starts to smell and you probably get tadpoles growing, like whatever. Well, the same thing happens in muscle because it it is this dynamic tissue that is meant to have flux. And flux means that once you're eating carbohydrates and carbohydrates are being stored in or glucose is being stored in skeletal muscle as the form of glycogen, you are meant to replace this, you are meant to remove it. It is not meant to sit there and never be disposed of because if you are an active, so liver glycogen, liver is this organ system that is the primary regulator of glucose, right? So through gluconeogenesis, this is this is really what is maintaining your blood sugar during an overnight fast. You are creating more glucose. You're not pulling from muscle glycogen. You're not pulling glucose from muscle, right? When you are exercising, it is it is discreetly utilised by skeletal muscle. It's not directly going to the bloodstream. And so we might be depleting liver glycogen through periods of overnight fasting, but we're not affecting muscle in that same way.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, I do like the analogy of like the pond or like a it could be like a fish tank where the pump are your muscles and you need to make sure that you're moving the muscles to create dynamism in that environment because otherwise you're going to get stagnant water and the fish are going to die and all the rest of it. So I I yeah, I definitely going to use that analogy for sure. Um let's quickly talk about carbohydrates then before we move on to the self-identity piece because people listening to this might be thinking, okay, fine, I'm just going to cut all my carbs and then I'm just going to eat protein. Uh what what are your thoughts on on that and how would you describe how would you talk people through it?

Dr Gabrielle Lion: Well, the first thing that I would say is you have to understand, um you're always going to have to eat and you might as well set yourself up for success now because you don't want to be good at repetitive patterns of inefficiencies and ineffective behaviour. Number one, it erodes your self-confidence and number two, it is not sustainable and adds to frustration that when a plan is put into place, you are less likely to follow it. Because of your anchoring bias or because of how you feel about it. And that's a mistake. Now, the way I think about carbohydrates is first of all, they're not bad. Carbohydrates, fats, we're not going to we don't need to label foods as good as bad. It doesn't need to have an emotional component to it. When we think about a plate, we think about a third of the plate is high quality proteins and then a third of the plate comes from fibrous vegetables, maybe low sugar fruits like berries, and then a third of the plate comes from starchy carbs. Typically, the current recommendation is 130 grams of carbohydrates a day. If you have signs or symptoms of unhealthy muscle and or you have weight that you want to lose, then you could easily start with 100 grams of carbs and then titrate up or down. It could be higher or it could be lower. There is a something called a carbohydrate tolerance. And so here is how we came up with this carbohydrate tolerance. So with all this discussion of protein, obviously my favourite topic aside from my kids, was made a lot of sense. It was how much protein do you need overall? If you are ageing or you are lower on the protein, how are we going to dose protein to stimulate muscle? And we say it's between 30 and 50, 55 grams. And then really this conversation about carbohydrates were, well, it's 130 grams a day and the rest is earned through activity. And by the way, the average American is eating 300 grams of carbohydrates and doing essentially three glucose tolerance tests a day. Imagine that.

Dr Rupy: 300 grams of carbs every single day.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: That's like three glucose tolerance tests a day.

Dr Rupy: Wow.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: So if a woman is listening, you know, that the gestational diabetes that test, essentially doing that three times a day. So when we were talking, Don and I were thinking, okay, so how do we design a diet for muscle-centric health? Well, we said, well, we have to calculate, we have to recognise that the majority of individuals are not exercising. We're consuming 300, the recommendation is 130. How much can a body dispose of that is not exercising and sedentary in a two-hour period? How much glucose can a body dispose of? So we did the calculation. And it was, you know, so we have obligatory need, which is brain, those obligatory organs, muscle, which was very few, it was like two to three grams per hour. And then it was um the other organ systems like gut, liver. It came out, are you ready for this? The glucose disposal rate and gluconeogenesis, we don't really know, you know, that's different for everyone. We don't we don't know what's happening. Are you ready for this? You're not going to believe this.

Dr Rupy: Okay.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: It came out to be 20 grams per hour.

Dr Rupy: Wow.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: If an individual is sedentary.

Dr Rupy: 20 grams an hour. Okay, so I'm going to do some math during the 12 hour period that someone's awake. So that's 240 grams per waking day.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: Okay. Now, in a two-hour period, we're talking about 40 grams of carbohydrates for glucose disposal in a sedentary person. Now, I want to be clear, I'm talking about glucose. I'm talking about whatever you are eating that then gets metabolised to glucose. Fructose is a whole different thing, but glucose, right? These primary carbohydrates that are then getting converted to glucose, the max that we can dispose of is 40 grams before we begin to distort metabolism. And guess what? If blood remains, blood glucose remains elevated after that two-hour period, we have a disease for that. We have a disease name for that. Do you know what that's called?

Dr Rupy: Diabetes.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: Diabetes. Therefore, if we take a step back and we recognise that dietary protein has a threshold, then we also can recognise that carbohydrates have a threshold. And that number, so if someone is listening to this, how do they begin to think about their own nutrition plan to eat for muscle health, which is arguably the most important organ system in the body because it is the lever that pulls the health on everything else. When you exercise skeletal muscle, you improve brain function. When you exercise skeletal muscle, you improve bone. When you exercise skeletal muscle, you secrete myokines that actually improve liver utilisation of nutrients. So there's nothing that gets worse through improving muscle health. Nothing. And that is very difficult for you and I to say in the landscape of of medicine, that this one organ system, which is a focal point, makes everything else better. There's nothing else that you can say for that, right? And so designing this diet is understanding that 40 grams or less if you are not doing some kind of activity. You can increase carbohydrate dosing if you are doing activity. So typically the number is, you know, at least, you know, at least 120 beats per minute, at least depending on your activity, you can add 40 to 70 grams of carbohydrates per hour of intense activity.

Dr Rupy: Even endurance cyclists and runners, like they aim for that with the glucose packs and stuff. So they're they're taking those little shots and it's around that that dosage and they'll titrate it according to what gives them the amount of endurance that they need. But that's essentially what people are consuming on a 24-hour period or a 12-hour waking period throughout the day without doing any exercise whatsoever. So it's and and just to sort of clarify for folks, when we're talking about 100 grams of carbohydrates, we're not talking about just 100 gram portion of of rice. We're talking about the carbohydrates within that carb source of food.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: Rice, pasta, yeah.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, exactly. So like 100 grams of carbs in a cooked pasta is something like 350 grams of of pasta. So that's quite a lot of carbs in that. And but these are generally what portions are these days when you when you eat out.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: I mean, think about it. If you have one bagel, it's like 60 grams of carbohydrates. So one bagel is probably around 60 depending on the size. And then maybe you put jam on that. So now per teaspoon, you're putting another whatever, 15 grams. So you're at 60, 75, you've exceeded your 40 gram dosage already. Yeah. Right? And then we're now forcing muscle to be able to tolerate this glucose. We're forcing the metabolism to tolerate glucose. And over time, it's, you know, we talk about insulin. So insulin is this hormone released from the pancreas to lower blood sugar. It is a fail-safe mechanism. It's not something that should be used daily. Meaning, we shouldn't be relying on releasing more and more insulin over time. It exists from my perspective and I would say from my mentor's perspective, to help us in a discreet moment, but not to be relied upon.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, yeah, because we have other mechanisms. It's almost like this beautiful evolutionary picture of like how muscles have we've evolved to have muscles to actually drive glucose into the cells where it can be utilised for energy.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: And there's one more thing. Yes, and there's another thing because I do want to touch on training because I think there's a lot of misconceptions out there. There is and I know that you I think you have like a 50-50 split, you have a female audience and male audience, yeah?

Dr Rupy: Yeah.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: Your producer's like, oh, no, she totally got it wrong, but go with it. Um and sorry, buddy. So there is this idea that women have to lift heavy. Number one, heavy is relative. And number two, if someone is untrained and you are telling them to lift heavy, you have to recognise that what puts people out is injury. Muscle strength outpaces tendon strength and tendon health. And as a practicing physician, when I'm hearing all this, you know, women have to lift heavy and do all this stuff, that's not true. It's not, it's about progressive stimulus. It's not about progressive overload. I would never tell my, you know, mid 70-year-old mom to go do a max out squat or anything or overhead pressure to blow out her shoulder. There's a mechanical part, also, you know, muscles get stronger faster than tendons get stronger. With the change in hormones, we see, so as people go through perimenopause, menopause, we see a change in tissue turnover, tendon tissue turnover. So in 2015, when I started my own practice, I would have these women come in and all of a sudden they would have elbow pain and then wrist pain and then ankle pain. And I was like, okay, well, I don't know, we should, you know, when you're a young physician and you're just like, oh, I don't know, we should, you know, we make sure that we got to test you for, I don't know, we're going to test you for Lyme and we're going to test you for Hashimoto's and then we're going to test you for rheumatoid, we're going to test you for these, right? You remember what that was like. You get much more skilled the longer you do it. But these women would come in and one of the things that I started to see over time is that their hormones were low and their thyroid was low and they were having challenges with this tendonitis, which was ended up being a challenge with tissue turnover. We corrected for that and their soft tissue injuries got better. They stopped having this repetitive, um these repetitive challenges. And so, uh again, I think part of is that we have to look at the evidence and the evidence would suggest that a good training program is a good training program regardless of sex. There's not different, we are all part of the same species. And someone would say, oh, but women have more estrogen. Yes, and I would say, but it's unclear as to the impact on skeletal muscle and a good training program will trump hormonal changes. And we saw that in some of the early research. So I worked on some of these early studies, this were some of the first of its kind that were very tightly controlled nutritional science studies that we used to pack their meals. And they were isocaloric. It, you know, both groups had the exact same calorie intake. One had the food guide pyramid, which was and also 0.8 grams per kg, so a lower protein, higher carbohydrate, also same amount of calories. The other group had double the RDA, which was 1.6 grams per kg, and had, I think it was, I don't remember the exact percentage, but it was a lower carbohydrate. It might have been 30 or 40%, but it was it was controlled in um the way in which we're talking about it. And what we found is that those and these were postmenopausal women, they were not on hormone replacement, simply by changing the macronutrients of their diet and adding in five days a week of walking and two days a week of resistance training, which was yoga, which I don't even like saying because I think that that they should be doing weights. They lost more body fat, improved lean tissue and all of their markers got better.

Dr Rupy: It's incredible.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: It was incredible. And again, it's we have to put things back into perspective and it's a multi-factorial approach of, you know, what are the levers that people feel comfortable pulling and it's not all one way and just and again, examining where the data begins and ends and then what becomes clinical practice.

Dr Rupy: Gabrielle, you've sold us on the importance of improving our muscle health, increasing protein to support that as well. I think where people fall down is this, okay, I just can't get myself across the line. And you talk really eloquently in your book about identity transformation with physical training. So, you know, your habits become your identity. Like what why do you believe muscle building is also a mental practice? Like how do how do people like adopt your mentality to this? They've been sold on the benefits, but it's like the other piece that is just as important.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: Well, I'm going to pose a question to you. Let's just say you had a really rough day. You now, for whatever reason, in your moment of weakness, are having repetitive negative thoughts. You cannot get it out of your head. And you might say, you know what? So just put yourself in this position. I am going to go meditate. And I'm going to ask you, you've had the worst day ever, is meditation going to take you out of it? And you might say, it might. Does it?

Dr Rupy: Sometimes, I mean, like, you know, I do like a good meditation session.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: Right. But the reality is, again, been seeing patients for, graduated med school in 2006, I've been seeing patients for a long time. In all of my time, it is very rare. So I have one of my best friends, her name is Elena Brower. She'd also be an extraordinary guest. She is now up for Buddhist chaplaincy, taking people, you know, through their life journey and planning their death, not to be depressing, but it's it's she just anyway, she's the only person I know that can literally uh meditate herself out of whatever mood she's in because she doesn't even get in the mood.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, I I envy those people so much. That's basically why I'm trying my darn hardest to meditate my way to a better mood.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: Right. I'm not that skilled. It's never going to be me. I understand. Now, you've now if the listener or the viewer can put themselves in this position, they've had the worst day. Now I'm going to ask you to get into a cold plunge or your bathtub with a ton of ice. And I want you to tell me how long you can continue that repetitive thought. And that answer 100% of the time is zero. It is impossible to have a negative narrative other than this effing sucks right now because I'm so cold. This was the worst idea. You immediately have now forgotten of whatever story, however terrible your day was. I I mean, I challenge you to do it. It's impossible. It's impossible because your physicality, your physical nature, your physical experience takes over your mental experience every single time. And let's say someone's like, well, I don't have access to a cold plunge. I know you have access to ice and you can dump that sucker into the bathtub. But let's say you want to give me that you can't do that. Okay. Then I'm going to say, well, why don't you do this? I want to see a max out bike sprint, a max out sprint, a you tell me whatever it is that pushes you into that red zone, and I will tell you it's impossible to have alternative thoughts. It's impossible. And this is a way in which, again, we have all these breathing tools and all these meditation tools. I got to tell you what, nothing works faster than putting yourself in a position that is so uncomfortable that it is impossible to focus on anything else.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, yeah, yeah. I I yeah, I mean, I definitely do my hit training against my own will and it's it gets you got to really push yourself to get yourself into that. And once you've done it, once you've finished that work, you feel incredible. Like you get all the benefits afterwards, but it's that again, it's that getting that into that moment where you even think that that's an option that you should be you should be doing. And and I think that's where people struggle. I mean, they want to get to your state. They want to get to, you know, Dr. Gabrielle Lion where you can you can pick yourself up after a heavy day like that and get and just be like, yeah, I'm going to jump in the cold plunge or I'm going to do an all out work. Like what what does that journey look like to get to that person across the edge?

Dr Gabrielle Lion: Well, I'm going to say one thing here. We don't need a lot of people, but we do need a few. And who you pick and choose to have in your life plays a huge role in how you live out your life and the standards that you set for yourself. I'm going to give you an example. And I I just I want to say this, you don't need a crowd of people, but you need a few committed teammates because when things get really tough, you're always willing to do it for another person. And I'm speaking absolutes, but at the end of the day, as humans, we're much more likely to do it for somebody else and show up for them and do the hard thing for them than we would be for ourselves. Right? Because there's this altruistic nature. Part of it is a stress response. It's this tend and befriend. If someone is in need, it turns your attention away from you and you're willing to to step up for that. And so I say this because it is difficult to do alone. And I have picked a teammate wisely, my husband, and it's not always fun. I'm going to give you an example. And it doesn't have to be a husband. And it does it could be one of your community members who can connect with another community member and it's setting a standard. So I was in Australia. So I was in so last week, over the last two weeks, I was in Portugal for like four days, home to tuck my kids in and then take them to the zoo and then left for Vegas for then came back from Vegas, then in a day and a half later went to Australia for two days and then came back. Okay? While I was in Australia, I was like, I am really exhausted. I have done a keynote, a book signing, a stand-in panel. I'm just going to go for a walk. So I go and I'm like walking and I call my husband and I'm like, ah, I just I don't think I can get to the gym. I'm I am wiped. I'm so tired. It's like 3:00 a.m. my time. And you know, I'm I'm I call him, I call him on FaceTime. I'm like, what are you doing? And he's he's like wearing his running gear, which is really dorky. And he's like, well, I just worked 36 hours. I signed up for a half marathon because, you know, one of the residents is doing it and I'm going to go do that. And I was like, wait. So just to be clear, he's a surgical resident. Just to be clear, he worked for 36 hours and now he is on his way to do a half marathon and I am just complaining that I'm too tired to do anything other than a walk.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Puts it into perspective, hey.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: I mean, okay. So just pick someone crazier than you and I promise you, because then I had to look at myself and I'm like, okay, you know, am I really tired? Yeah. Am I am I going to feel better if I go lay down? Yes, but could I spend 15 minutes in the gym doing pull-ups and push-ups or whatever? You know, could I could I do that? I could. And then I I think that um so number one, you don't need a crowd, but you need the committed and you need someone who inspires you. And I don't mean that to be disempowering to choose other people, but again, we are are community driven individuals or um, you know, humans. And then the other thing is that set a standard that you will if you allow yourself to find an excuse, you will, but if you also allow yourself to find a solution, you will. And one of the biggest things that I see is people set goals. And they go, you know what? My goal is to lose these five pounds before going on break. I already know that that's never going to work and this is setting this person up for a failure. Because if we set and listen, people might totally disagree, but if we continue to set goals, then we never internalise those habits to become that type of person. And if we set a standard and we really set a standard for our families, then we recognise that these children of ours, you know, you and I are both parents of of young children, that we're not raising kids, we're raising adults and our standards will allow them to develop habits that they can either choose to utilise or not utilise versus spend 20 years trying to unbreak bad habits. So we, our family, we get up in the morning before school and we train. This is not a goal. This is not a quote enforced. This is purely choice. Sometimes my daughter doesn't like to get up, she's six to do it. My son, every single morning.

Dr Rupy: I love that.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: I mean, listen, he's training for the SEAL teams right now.

Dr Rupy: Really?

Dr Gabrielle Lion: And guess what? And guess what? He's four. I'm not joking. It is bananas. And so when this is crazy, right? So I myself and my husband, um we don't feel like getting in the cold plunge and our four-year-old son is like, come on, time to cold plunge. He's like, I'm going to cold plunge. I'm like, oh my god. And my my husband and I were both looking at each other like, forget it. But he's in there, right? He's not like staying in there a long period of time, but he is all about it. He's like, Mom, it's time to do push-ups. And so, um you know, I'm witnessing this identity, this person, this little being, right? And my and again, we don't force it. My daughter, she's actually very physically gifted, but I think life is going to be hard for her because things come so easy. Whereas my son, he's a little, he's my size. He's smaller, he's tinier, but he recognises that he has to practice. So before bed, he was doing sprint. I walked downstairs and he's on the treadmill. We have a a self-powered treadmill, like those those rogue, those self-powered, he's doing sprints. He has his underwear on, he has his trainers on, and he has his Christmas pajama tops on. He's like, Mom, I got to get ready. I'm training for the SEAL teams.

Dr Rupy: That's amazing.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: It's hilarious. Never seen anything like it. You know? Um and so I think that instead of setting goals, we set standards. And these standards become our identity. And then life becomes easier.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, I love that. And I love setting those standards. I mean, it's like one of those, I don't think I've actually articulated it in that way before, but the things that I do in the mornings have become habits because those are essentially my standards. So my meditation practice in the morning, even though I suck at it, I'm still doing it every morning. My stretching routine every morning, my training routine that has been taken to the wayside because of my one-year-old, but like I can't wait to get back to that standard because that's what I've set myself. Um and I think the more people think about that rather than like a goal that can slip off and then you can sort of like forgive yourself from like slipping up. Um that's a much uh a more effective way of training for life and actually, you know, giving yourself a better try. Yeah.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: It's exactly right. And also, what I would encourage you to do is I would encourage you, so having a one-year-old, so we have a a four and a six-year-old and it's tough. And I and I don't have full-time care because I want to raise my kids. So um it becomes challenging. And so what I've done and it's hard with one because you can't really um convince a one-year-old that this is fun and we're going to go train. But what I have found is that I have found ways to incorporate the things and the standards that we reinforce in our family. So um we talk about things as a family. So it's it's not that, oh, pick this up that this is on the floor. It's, hey, you know, uh as a family, we keep the house clean. As a family, we appreciate physical activity. It's important to us.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: And um you know, for you, one is challenging, two is challenging. So what I would say is how do you incorporate going for a walk with a weighted vest? Yeah. Yeah, yeah. How do you because you're not, listen, it's hit or miss in the morning. So is there a way that you have a bottle or something set up where you're up and out? And let's say the baby doesn't want to go in the stroller, you're putting the baby, you know, maybe the baby's strapped on and you're pulling a, I don't know, a sled.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: It's crazy. It can totally be done.

Dr Rupy: I'm very lucky. It's, you know, I think we've both picked our partners really well in that sense because my wife is like, she's Pilates mad and she started doing weight training as well, particularly when she was was pregnant. And when we're in LA for a month, we would do the hikes on like, you know, the Runyon Canyon and all that kind of stuff. And she would just put him on the carrier and she'd be having like a full conversation with me. I'm like, gosh, your VO2 max must be like amazing because like, you know, she's just so used to like putting him in the carrier and stuff. And so he does become part of our workouts. Um particularly at the weekends when we can't like peel off and go to the gym and stuff. So we've tried to incorporate him as much as possible. Um what I did want to ask you about as we bring this to a close, Gabrielle, is recovery. So I, you know, I'm 40 this year. Um I'm thinking a lot more about how much I can push my body, but how my recovery is actually taking a bit of a hit. And I know you talk about this in your book as well as the other parts of, you know, thinking, moving, eating. How do how should we be thinking about recovery? How do we incorporate recovery? Because the last thing I want is someone listening to be like, great, I'm going to do my hit training, I'm going to like lift heavy weights, I'm going to get into all this stuff and then they get an injury into your point that you made earlier, that's the worst thing that you could do for for longevity and muscle health.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: I love this question because this was my hardest chapter. Because recovery has been the hardest challenge for me. And we have to reorient ourselves to this idea that it is where the transformation actually takes place. It doesn't happen, perhaps mentally it happens when we're training, but physically, in the moments, those quiet moments of recovery and rest is where we actually grow. And it's very metaphorical for all things. And um I will say, which I'm not excited about to say, but it seems as if and the data would support that sleep is really imperative for recovery. Now, I will say I think there are individuals that have genetic capacities that allow them to sleep less, but I only say that because I want to be one of them, but I'm probably not, but I, you know, I think transparency is always important. But sleep is very valuable. The other thing is there's protocols for sauna, there are protocols for ice. All of those things, there's also recovery can be not quote rest, but actually active recovery to move blood flow. It can be walking. There are things that can be done where you're not taxing your body, but you're also improving blood flow. And there's some data to suggest that walking and movement is more effective than stretching. Again, they probably do two different things. I would argue that that's that's reasonable. But the transformative aspects begin in the moments of recovery. And I will say one of the things that I've begun to do, so I always do hot and cold. I love to do sauna and I love to do cold plunging. It's just it's a thing. But getting out in the morning early and really anchoring the circadian 24-hour cycle is extremely valuable from a deep sleep standpoint. So sleep actually starts in the morning and your ability to maintain energy levels are really affected by two things primarily, the first moment that you have food and the master suprachiasmatic nucleus of the body, which is the the light coming in to the eye. And those two things we have control over and anchoring that early and and trying to recognise and be in sync with what is happening within our environment can be very valuable and make recovery easier for the individual because I'm sure a lot of your listeners are like, I don't really want to recover, I'm over it because I have been that person for many years. But in all fairness, you want to pace yourself so that you are actually making improvements. And the way to do that is not just to push hard, but also to recover equally as hard.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, I feel like my age is definitely a forcing function for that because in my 20s and 30s, I could just like train and I don't have to worry about recovery. But now my body actually tells me when I haven't had enough sleep. So what I'm hearing is some heat, some cold, active recovery and being conscious of one's circadian rhythm with those two stimuli being food and light. Um those those are really important and that's definitely something I'm trying to optimise ever so slowly. I want I want to do a bit of a quick round, quick fire round with you to finish this off. Are you up for it?

Dr Gabrielle Lion: Yeah, yeah. You got it.

Dr Rupy: Okay. Uh let's go for your favourite strength training exercise.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: My favourite, oh man, I don't know if I have a favourite. I love, I mean, I love kettlebell swings.

Dr Rupy: What is the most misunderstood nutrition myth you wish the public would retire?

Dr Gabrielle Lion: This idea that we are, it's this protein conversation. The RDA is um quote the minimum for not being worse than yesterday. But the biggest thing and also I wish scientists, I wish that the the medical community would understand this, that based on nitrogen balance studies, nitrogen balance, a technique from the early 1900s, it has no viable health outcome. And so we're talking about the RDA and is is it too much protein, is it too little? The number, the RDA number is irrelevant. We don't have outcomes for nitrogen balance that are meaningful health outcomes.

Dr Rupy: Okay, if you could rewrite the food pyramid for 2026, how would that look? The base, let's just talk about the base, the base.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: Yeah. Well, um well, we've broken up into thirds, so it wouldn't be a pyramid at all. It would be a plate. It'd be a third lean proteins, a third fruits and vegetables, and a third starchy carbs.

Dr Rupy: Love it. And if someone's listening to this, who could just do one thing tomorrow to become forever strong, what would it be?

Dr Gabrielle Lion: Number one, the obvious, you'll never regret being strong. Be strong, train strong. And number two, know your weaknesses and plan for them.

Dr Rupy: Epic. Gabrielle, you're awesome. Thank you so much for sharing your wisdom and your knowledge. You're just such an inspirational character as well. Like I know loads of people are just going to listen to this and get pumped and and run to the gym after this and start eating more protein. So you're great.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: Thanks. And I want to say one more thing and you guys can cut this out, you can leave this in. But while I'm talking about, and I think that you'll appreciate this as someone who's practiced medicine, on the surface, I'm talking about protein and muscle. But underneath it all, what I am really talking about is building stronger, more resilient humans and recognising that strength is a responsibility. On the surface, it's all about muscle and protein, but that is not the point. The point is we are at a precipice, we are at a moment in time where we have the opportunity to build stronger, more resilient humans and muscle is finally getting the recognition it needs, but it is so beyond muscle per se. And it's so it's our responsibility to do it for not just for ourselves, but for the next generation. And medicine is the modalities. So medicine is the entry point, but strength, both mental and physical is is the outcome.

Dr Rupy: Amazing. Love it. Thank you, Gabrielle. We appreciate you.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: All right, friend, so fun as always. You're just you're one of the best podcast hosts, period.

Dr Rupy: Oh, that's so sweet.

Dr Gabrielle Lion: I do it all the time. Trust me. You're I I you're great.