Dr Yael Joffe: So when we eat these foods, these incredible plant foods, these incredible vegetables, they switch on genes which switch on our detoxification pathways and optimise our ability to clear toxins from our body. So that's just one very, very small example and the name of this compound is called sulforaphane, which in my opinion, I could talk about for hours in itself, but in my opinion is probably the greatest plant molecule that we have discovered in food in this century.

Female Voiceover: Welcome to the Doctor's Kitchen podcast. The show about food, lifestyle, medicine and how to improve your health today.

Dr Rupy: I'm Dr Rupy, your host. I'm a medical doctor, I study nutrition and I'm a firm believer in the power of food and lifestyle as medicine. Join me and my expert guests where we discuss the multiple determinants of what allows you to lead your best life.

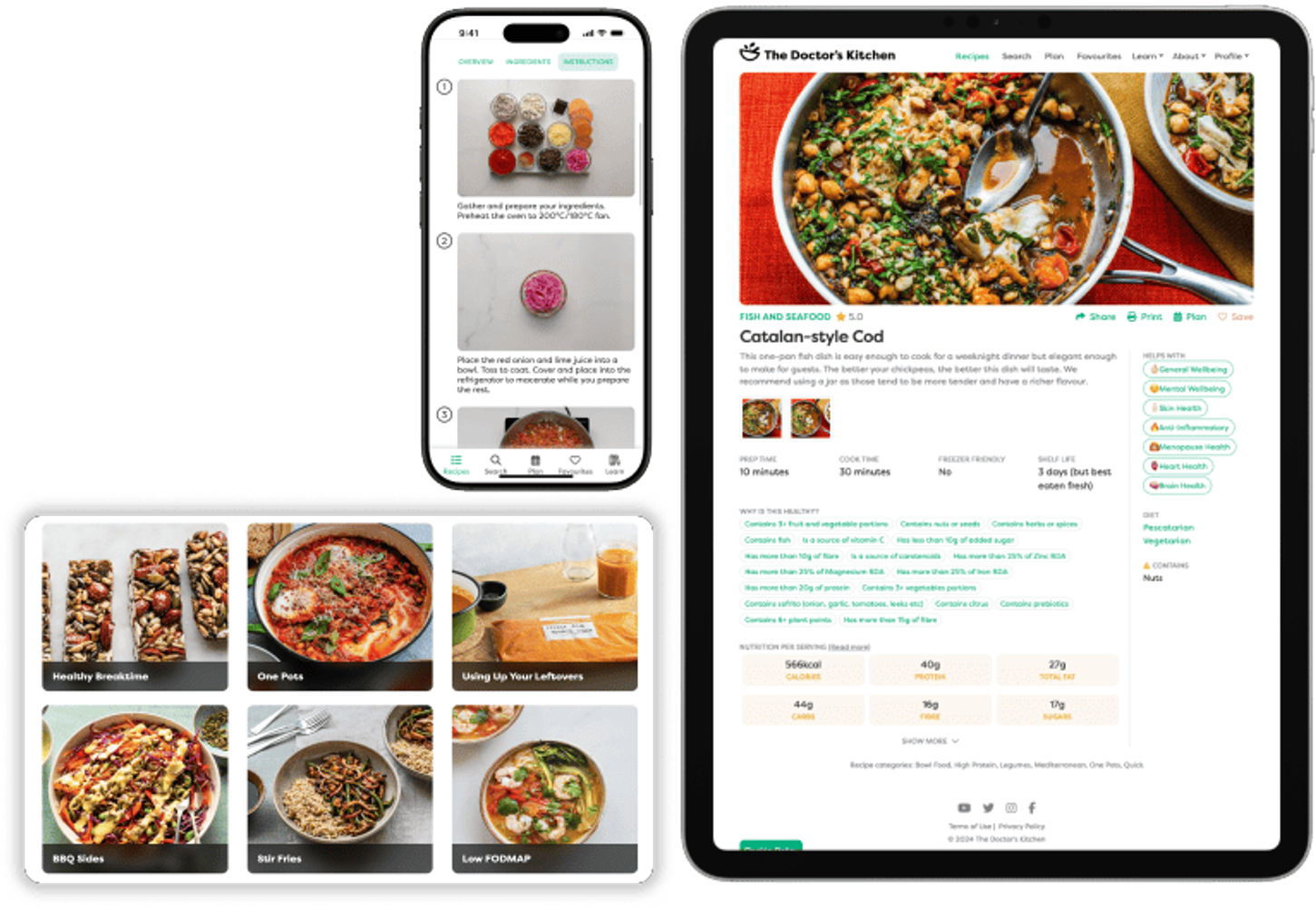

Dr Rupy: Today's podcast is all about nutrigenomics and medicine and I've got an incredible guest, Dr Yael Joffe, who is a registered dietitian and scientist in South Africa who specialises in nutrigenomics and functional nutrition. She has been involved in several research collaborations with key academic partners from around the world and is often to be found at the front lines raising awareness about nutrigenomic and functional nutrition applications for both health practitioners and the public alike. Yael obtained her PhD from the University of Cape Town, exploring the genetics and nutrition of obesity in South African women. Today we talk about a ton of things. So nutrigenomics 101 is pretty much what we're doing here today. We talk about what a gene is and how spelling mistakes occur, also known as snips. The difference between monogenic and polygenic genes and the processes determining which spelling mistakes to include in a genomic profile and how that goes about. Detoxification and how important it is, particularly in an ever-polluted world. We talk about the change in gene technology over the last 20 years that has rapidly reduced the cost, making consumer tools more available, but we also talk about the pitfalls within consumer tools as well. We talk about appetite regulation, detoxification, sulforaphane and the relationship with NRF2 or Nerf2, but it's NRF2. The differences between ethnicities and actually the lack of genomic research in non-Caucasian people, which is quite worrying, but hopefully there is going to be more research because again, this does lend itself to health inequalities as this research becomes more and more available. And that's something that we've seen throughout research over the last few decades. Alzheimer's risk and the importance of APOE4 and we do talk about COVID. There's so much more that I really wanted to dive into with Dr Yael, but unfortunately we did run out of time. This isn't a sponsored podcast in the slightest, but she is one of the founders of 3x4genetics.com, which is only available to practitioners who are educated in genomic counselling. So this isn't a consumer tool, but I do see the value of nutrigenomics and I'll be honest, I was a bit of a sceptic as of a year ago, but the more I find out about genomic testing and the advances in microbiome testing, I am coming round to the idea that this should be standard practice to give people empowering information about how they should be living according to their manual. But without further ado, this is my conversation with Dr Yael. I'm sure this won't be the last one and you can find out more about her on the show notes at thedoctorskitchen.com. Whilst you're there, do give us a five-star review, join the website newsletter, we give out recipes every single week, as well as what to eat, listen to or watch or read every week to help you live a healthier, happier life. I wanted to start actually just talking about your own journey actually and how that led you to dietetics and to become a scientist with an interest in genetics and now nutrigenomics. Why don't we start there? Because I'm always fascinated as to how people get to this point.

Dr Yael Joffe: Okay, great. So it is a story because I actually started out in architecture and not in nutrition. In fact, I never studied science at school, had no interest whatsoever in it, wasn't one of those people that knew what I wanted to do. And while I was studying architecture, my grandmother got sick, very sick. She had like end-stage cancer by the time they found it. Doctors had very few answers for me about how we could help her, why she got it. She had a GI cancer, so she was like riddled from top to bottom. They couldn't tell me what to give her while she was sick. It was just this like deep black hole of no answers. And so while I was sitting, she was the only grandparent I had and and so I was really, really broken by it. And when I was sitting with her in the last couple of months, I remember saying to her, you know, architecture's great, but this really seems like we should have been able to do more for you or help you more. I think I'm going to change degrees. And and that's where it actually happened. And funnily enough, she did pass and literally that day, I walked into architecture and handed my my end of year final in and I said, I'm done. And the problem I had then was I actually didn't know what I wanted to study. So I knew that I wanted to study health. I knew that I was looking for answers around my grand's death, but I didn't know where any answers lay. And I was looking for this degree in health, which you can imagine how difficult that can be. So we all go find the degree we think is closest to health. And it was kind of between medicine or dietetics. I mean, literally in the in in those years, in kind of the late 1980s, that was all that was on offer. And I chose dietetics, which went well for about three weeks. And then I was completely horrified, completely horrified at this profession that I had stepped into when my lecturer said, you know, you can give a patient in hospital chocolate cake and ice cream because it's got calories and protein and carbohydrate. And I was like, oh my god, I think I've just landed in the completely wrong place. And so that was like three weeks into a five-year programme. And I was like, okay, well, do I leave and go to medicine? Do I try something else? Like, what do I do? Anyway, I decided to stay, spent five miserable years hearing about chocolate cake and ice cream. It never got better. I was a horrible student, as you can imagine. I challenged everything. I knew so little. I was reading like the optimum nutrition, like I was like Patrick Holford, you know, challenging everything because that was the only place for me to go and kind of learn stuff. Anyway, so I got my degree and and left dietetics, went travelling around Europe, spent five years living in London. And the only way I could travel in Europe is by working in London and then earning some pounds and then going travelling. And I landed up at a nutrition clinic in Harley Street, doing some kind of research for them. And I was approached by this amazing startup called Sciona, who were based in Havant, near Southampton. And they were had this idea that you could build a company out of nutrition and genetics. And I thought they were insane. I mean, there was no connection for me between nutrition and dietetics. I didn't know what they were talking about, but I was kind of had a backpack and I was cruising around and I was like, well, this sounds interesting. It's a lot more interesting than what I learned. I'll go spend a few days with them, which I did. And I still didn't understand anything, but there was something in their conversation that just excited me, that inspired me. I was like, genetics and nutrition, there's something in this. And that was in 2000. So it was a long some time 2000. They were the first nutrigenomic startup in the world. They came out of Havant. I was the first employee. The founder was a geneticist, Dr Roslyn Gill-Garrison. And she said, do you want to join this company? I was like, I know nothing. I know nothing. And she said, don't worry, no one else does. And that's it. And that was my beginning. And I spent seven years with them and went from like reading a textbook on biology to eventually going back to university when I like four years into it realised that I really did not know what I was doing. And so I went back to university and got a PhD in genetics and that's how I that's how I got into it.

Dr Rupy: That's amazing. That's amazing. Well, I I want you to treat me like you were 20 years ago, not knowing anything about the field because a lot of people who listen to the podcast, we have a varied audience, right? So we have practitioners, we have doctors, but we also have a lot of the the public who are really interested in this field but are really confused and conflicted because there's so many different mixed messages out there. So why don't we strip it right to the basics and talk about what a gene is, how we are similar as humans, I think it's around 99% or some percentage that's very, very high in terms of similarities versus the the minority of differences and how they play out in disease propensity and and risk.

Dr Yael Joffe: Okay, so like nutrigenomics 101. No problem. No problem. Right. So what are our genes? So let's go down to the basics. The basics are that our DNA and our genes are really our blueprint. They are like this code that we have that we all have inside us that really determine how we exist in the world. And this this code is made up of a language of genetics, which is basically instead of having 26 letters like we have in English, we have four letters in DNA, A, C, T and G. And these letters come together to make words and the words come together to make sentences, which we call genes. And when they come together to make sentences, they start telling a story about who we are. In this story, we are 99.9% the same. So that means in our DNA sequence code, we are 99.9% identical. But what we're actually interested in is not the similarity, we're interested in that 0.1%. Which means that a 0.1% in our DNA sequence, in our story of ourselves, we differ from each other. And I call these our spelling changes because that's all they are. They're not sinister, they're not going to tell us, they just where we have a different spelling. So instead of having a C, we may have a T, instead of an A, we may have a G. But what's interesting about these spelling changes is that sometimes, not always, but sometimes they will change the way the word is written, which means they'll change the way the sentence comes out. And when that happens, we can get changes in our body. So a spelling change can change an enzyme activity, a hormone activity, a brain messenger. A spelling change can change the colour of our hair and the colour of our eyes and our blood type. So these spelling changes are really give us insight into who we are in the world, but most importantly, how we respond to the world. So I always say like the word of nutrigenomics, which is nutrition genetics, is just another word for responsiveness. How do we respond to the world around us? How do we respond to the food we eat, the supplements we take, the exercise we do, the pollution that we live in, the toxins that we consume, the trauma that we endure, because we all exist in a different way when we respond to this. So when I meet with patients, I always say like, let's just think about who you are in the world and how you've been responding to the world, and then let's look at your DNA and get insight. And that for me is the key word, insight. Genetics gives you insight into who you are and how you respond to the world. But there's a second part to the conversation. So that's 50% of the conversation, which is I want to understand who you are and I get insight from this code that you have. Now, the cool part of it is if I can understand who you are and I can understand what spelling changes you have that are making you different in the world, I can now make some really, really clever and personalised decisions around you to improve your health, to prevent disease, to manage disease, to help you lose weight, to help you train better. And that is because the food we eat, the supplements we take, the exercise we do, switches on and switches off our genes. And this is a very fancy field of genetics called epigenetics, which is outside genetics, but actually it's just switching on and switching off genes. So on one side, our spelling changes determine who we are. I call that insight. And the second part I call action. What are the decisions we can make each and every minute of every day that are going to switch on the genes that are going to drive your health and switch off the genes that might be harming your health.

Dr Rupy: Fantastic. So that gives us a brilliant oversight as to, you know, the nutrigenomics and and nutrigenetics and the process of that. I think a lot of people might be a little bit confused as to what they were taught in primary and secondary school with genes and how they hard code our eye colour, our our hair, you know, some of those those areas that we know we can't change versus now what we do know about the modifiable genes. So could we separate those out a little bit more?

Dr Yael Joffe: So for the first like 10, 15 years that I was in the space of genetics, there was this idea that our genes are set in stone, that whatever we inherit from our parents is what we got, tough luck, you know, let's just move on. This is what So like I got genes that make it hard for me to lose weight. Well, that's my lot in life. I'm moving on. But what has been the most exciting field of genetics in the last 10 years is understanding that while the sequence of our genes gives us information about who we are, we have come to understand how we can change the way the gene expresses or behaves. So, yes, we're not going to change our sequence. So this is not gene editing. We're not going to swap Ts for As and Cs for Gs. We're simply going to understand how you exist in the world and who you are. But the true power of genetics is actually this idea of switching on and switching off genes. So if we, let me give you an example because I think that's sometimes works better. So I can look at your DNA sequence and I could look at some spelling changes and I can see that you are more prone to having an inflammatory type body. So what we call low-grade inflammation. So not walking around with a burning temperature, but you have this kind of low-grade inflammation. And low-grade inflammation actually has a huge impact on diabetes and obesity and arthritis and cognitive function, all kinds of things, right? Now, we know which genes are driving this kind of inflammatory response. And we also know there's some really good foods and things that we find in these foods that can switch on or switch off genes. So for example, we know that the everyone knows that the omega-3 fatty acids that we find in the kind of oily and fatty fish are really good for you. But one of the reasons they're good for you is because omega-3s can switch off inflammatory genes. So everyone knows they're good. I don't think everyone understands why they're so good. And the main reason is omega-3s are really powerful on dialling down that inflammation and they do it by switching off genes that are inflammation inflammatory and that are switched on.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, absolutely. And and just talk me through the the spelling changes that we're referring to them as the single nucleotide polymorphisms and how we learned about which of those snips are responsible for what we see phenotypically, i.e. the the physical manifestation of them. And how we've also been able to take that amount of data and put it toward a testing facility testing process where we can confidently group them together and say, you know what, if you've got these, then this is your likelihood of X.

Dr Yael Joffe: Sure, that was a huge question. I'm going to I'm going to break it up into a couple of things because it's also quite a controversial area for me about how we have managed snips. So I'm going to call this I'm going to call the spelling changes snips because it stands for single nucleotide polymorphism, which means at one place, these little letters in our DNA are called nucleotides. So at one place in our DNA, we've changed one of our nucleotides. So how do we how do we understand these snips? So the scientific literature and the research that's been done basically has a look to see if when we've got one of these spelling changes, it changes something in our biochemistry. So biochemistry is just the chemistry of our bodies. So if we have a snip and we measure how much inflammatory marker we have in our body, is it higher or lower than those people who don't have the snip, right? One of the problems we've had in the industry and in the science and in the field as a whole is this idea that you can study one of these spelling changes and make an assumption that I have this disease because of the spelling change. So at this point, I'm going to talk about this concept of what of what we call monogenic versus polygenic. Monogenic means there's a spelling change that is so powerful that by itself, it can cause a disease. And there are quite a few of these genes in cancer. The BRCA gene is very powerful, not completely powerful, but a very powerful, familial hypercholesterolemia gene, the haemophilia gene. So there are genes that if you have the spelling change, your chance of getting the disease are very high. And we call these monogenic because it's mono, it's one gene that's very powerful, or the other way we refer to them in the science is high penetrance. They are highly penetrant or very impactful. But actually, that is not the space of nutrigenomics and that is not the world that you and I live in. The world that you and I live in is this idea of low penetrance gene variants. And what that means is there's a spelling change, it's doing something to the chemistry of our body, but by itself, it is not causing a disease. And one of the other reasons we understand it and we we're interested in it is because it interacts with the choices we make in our diet, our lifestyle, our decisions around smoking, pollution, etc. Now, one of the problems with the industry as a whole at the moment that I feel quite strongly about is that many, many companies have taken these snips and put them onto pedestals and said, you have the MTHFR snip, therefore your chance of getting autism or heart disease or Alzheimer's or anything is very high. Which is a blatant, blatant untruth. These low penetrant gene variations are not that powerful. You cannot make decisions around disease, you cannot even make decisions around diet, you cannot make decisions around supplements. So often you see genetic testing companies that will have a list of genes and a list of supplements. Absolutely no way, right? They're not that powerful. Genetics is only one part of who we are. Genetics gives us information about who we are. But if I'm a practitioner seeing you as a patient, I want to know your medical history, I want to know your psychology, I want your social, I want to know about your family, I want to know what your goals are, I want to know about your diet history, and I'm going to take all that stuff I know about you and your blood tests and put it together with your genetics to understand. So the one way that I've got around this, and this is something that I really have come to only in the last like four or five years of my professional career, because I was part of this kind of single snip brigade for the first 10, 15 years of my career, thinking that a single snip could give an answer, is I realised that you actually need to group them. So if you look at a process in the body, a metabolic process, so say detoxification in the body, and detoxification has a whole lot of stuff that has to happen so that a toxin that comes into your body or that's made by your body will get out of your body and not harm you. There are a whole bunch of genes that are going to impact how efficient you are or how optimally you detox. And I realised that if we could look at all the gene variants, all the snips in that detox pathway and group them together, we would have a much better idea of how impactful your genes were on a process in your body rather than trying to overreach the science or over extrapolate and just say, here's a single gene. So I'm answering the whole question you asked me. The last part of it, right, is you said, how do you choose these genes? Because if you're a health professional and you're trying to decide what company you want to work with in the marketplace, you need to be able to ask that company how they chose the gene variants, the snips that they included in your test. Because another thing that's happening in the marketplace is we've gone the the cost of testing has decreased. So the amount of money we're paying to test 500,000 gene variants today is the same amount of money we were paying to test 20 gene variants in the year 2000. So what's happened is companies are saying, well, instead of doing testing 20, I'm going to test 1,000 and when I sell it to you as a consumer, you're going to think I'm a fantastic company because I'm getting 1,000 gene variants. And the other company down the corner is only selling 100 for the same price, so you must be a better company. But actually, that's not the truth is the opposite. Because we don't know that much about that many genes. So if they've put in 500 or 600 or 1,000 or 400, then the chances are they only know about a couple of hundred and the rest are like stocking fillers at Christmas time, right? So you need to be able to ask the question of how did you choose those snips which you've put in your thing that I know that the science is excellent and robust and replicated and statistically strong and affects the biochemistry of the body and they're not just weird like general association studies. And the other thing I want to ask that company is, how do I know that that gene variant will have a clinical impact on my patient or on me as a patient? How do I know that it's going to help my dietitian or my doctor change their decision making? I want to see that proof. So I read, yeah.

Dr Rupy: That's the big answer to your question.

Dr Rupy: No, I think that I'm really glad we're talking about this because I don't think it's brought up enough and I don't think the average consumer will understand the process by which you need to go through those different steps to ensure that you're you're putting out a robust test. And I think the other thing that I'm personally a bit confused about is the variation in technology that's used to determine the snips in the first place and whether that has changed over the last 15 or 20 years and if there's variation from company to company, if there is a difference in in the technology itself.

Dr Yael Joffe: Yeah, all of that has changed. So the technology has changed a lot in terms of what's accessible. So a lot of technology that was only kind of available at university research level is now available to a company. And in fact, the limiting factor on launching a genetic testing company is not the technology because most companies, even my own, we don't do our genetic testing ourselves. We go to a certified laboratory who specialises in genetic testing and they do our testing for us. But the problem is there are different kinds of testing. And we see this with companies like 23andMe. So when you see a genetic testing company that's selling a product for like 200 or 300 pounds or euros and you're seeing a company that's selling it for 50 pounds or 50 euros, you need to ask yourself, what are they testing, right? So there's a couple of reasons why a company like 23andMe will offer a cheaper test. There's another answer to it, of course. But the the there's a difference between what we call clinical grade testing or high pass testing and low pass testing, which is kind of population testing. And that is when we test, so when we test for a gene, in our what we call microarray, which is like a plate that does the test, we test for the same spelling change three times. And if we we have to get the same answer on all three tests before we'll say that's the same, that's the right answer. But obviously that's more expensive because I could have filled up those three wells, you know, with with other genes, I could have reduced the price of the test. So that's what we call clinical grade. In low pass testing, we do not do multiples of the gene. So whatever we put it in the plate and we run it, it's much cheaper, you can do a lot more genes, but it doesn't, it we say it's not conducive to clinical decision making, but is very useful for things like ancestry where it doesn't have that kind of clinical impact. So that's one of the issues that have been identified around companies like 23andMe that can run these huge data sets at a really reasonable price.

Dr Rupy: Right. So feasibly, what you're saying is some people could be told that they have a snip when they that's actually incorrect.

Dr Yael Joffe: Very feasible. But so we know that there's an error rate in labs. We know that genetics is not perfect, but it should be like, it should be like 99.9% in a clinical grade lab. I mean, there's always a 0.1% because sometimes we have like a a letter inserted into our DNA and it shifts out our DNA, which just makes it impossible. So there is a naturally occurring error rate, but we do find in the low pass testing that that error rate will be higher.

Dr Rupy: Right, right. Okay. And when it comes to getting a test, how do you advise people to utilise the the manual, let's say, let's call it, you you get this clinical grade manual, it's basically tells you what your body can and can't do. How how do you advise people to utilise that information in a pragmatic way?

Dr Yael Joffe: So my advice is if you're going to go down the road of doing a test and find out this amazing information about what's inside of you, you need to do it with a health professional who's been trained to be able to interpret it for you. And this is one of the problems is that if you're a direct to consumer company, it's very hard to impart the value that DNA actually gives about who you are. So what happens with direct to consumer companies is they usually land up dumbing down the science to be able to give it to you in a way that is kind of not going to cause you alarm or anything like that. So it takes out the real value. And I always say often what happens with these companies is they land up selling data and not insight. And so companies like 23andMe where they're not able to sit with you and say, well, I found this is a great insight about your cholesterol or about your glucose insulin. Let's talk about your family history. Let's have a look at your your blood tests. Tell me what you're experiencing. Then we can extract value from DNA. When you're just getting a report that you have to download and you have to try and figure it out yourself without having any experience of genetics, you might as well be paying five pounds for it because the value you're getting out of it is decreased. So I'm a really, really strong proponent of of training health professionals, which I've spent a long time doing because if health professionals don't know how to interpret genetics, it's still just data, right? And then creating clinical value around it. So I'm I'm a big fan of find the companies that have trained, educated, mentored health professionals and that would be a great start.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, yeah, absolutely. So let's talk about a few examples. I think it's always quite nice to make it more tangible for the listeners as to how this plays out in practice. So you personally group a number of different polygenic snips into various factors. That gives someone an idea of where they have advantages and disadvantages. Can we go through a few different examples where it's quite there are quite meaningful changes that people can make in their lifestyles?

Dr Yael Joffe: Absolutely. So let's think about so here's an interesting one. Let's talk about weight because everyone loves to talk about weight. So one of the experiences in my life as a dietitian, especially in the early years, was this frustration around patients who were telling me that they had reduced their calorie intake, they had increased their exercise, but they weren't losing weight. And the way I was trained as a dietitian was if someone said that to me, I would be like, you're obviously cheating, you're obviously lying to me. So it was like the greatest awakening for me when I studied genetics to understand that there is such a huge spectrum in how individuals gain weight and lose weight. And when I started, and this is really where my PhD work was, was when we started uncovering why are people so different in the way that they they manage their weight, we found these really interesting areas. So I'm going to talk about one area. So in my report, we have 36 pathways, 36 of these metabolic pathways. One of them is around the idea of appetite, hunger and satiety, which is fullness. And even though I'd been a dietitian for 10 years, it had never occurred to me that I feel hungry in a different way from you. That when I haven't eaten for 12 hours and you haven't eaten for 12 hours or for 24 hours, our our experience of hunger is completely different. I might be so ravenous that I would eat this desk, I would like eat my arm, I would just eat anything and you'd be like, yeah, I'm a bit nibblish, I probably need a snack. What is that about, right? And so we started understanding that there are genes and spelling changes in genes that will change the way that we experience hunger. And we started seeing this when they started doing twin research. So twins, identical twins are the best way of doing genetic research where you see, especially we've got two twins with the same DNA, but they're brought up in different households. Okay. And that's how we started learning about this. And also children don't have that kind of experiential drama. So they're not comfort eating, they haven't mostly haven't been traumatised, they don't have the huge exposures to environmental eating behaviour. So they're more pure way of doing genetic research around around weight. And we discovered that there were children who had these insane hunger, this insane appetite that was out of control. And we started understanding what genes were responsible for that. The same thing with feeling full. So you and I have now been fasting for 12 hours, we go out for lunch, I order one cheeseburger and fries, chips, whatever we call them, always get confused. You you order like a burger, we get to the end of lunch and I'm like, you know what, that was really nice, but I think I'm going to have some dessert now just to like make me feel full. And you look at me and you go, are you insane? That was like a huge meal, like I can't breathe after that burger. So how we experience satiety or fullness is also very driven by our genes. So if I'm your practitioner, I'm your dietitian and you've come to me to talk about your weight and the battles of your weight and the many, many weight loss programmes that you've tried in your life that have failed. And I can have some insight about your the genetic impact on your hunger, on your appetite and how you feel, we can suddenly have a completely different conversation about your journey with your weight and we can also now start thinking about ways to manage your experience around food that we hadn't thought about before. So that's just one amazing when we we spoke about this concept of insights and responsiveness and this is just one example.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, no, that's fantastic because I think it certainly empowers the patient to have a different conversation with themselves actually as well and explain to themselves that, you know what, it's not due to lack of willpower. This is something that's actually part of my makeup and I have to manage with my environment. I mean, just that around appetite is something for me, like I know I can't keep junk food or high sugar items in the house because I will eat them because I know they're there. So that's actually helped me manage my own environment at home. And I think if it was something like in a report, that is highly, highly motivating. One thing I've heard you talk about before is this whole concept around detoxification. And I think in an environment now that is becoming increasingly polluted, I mean, I'm I'm sat here in the middle of London and there's aeroplanes, there's urban traffic, there's plastic, etc. I think this conversation is becoming a lot more important. Are there snips or snip profiles that we can look at and determine how good or bad we are at the process?

Dr Yael Joffe: Absolutely. And in fact, detoxification is probably one of the most important pathways that we look at. And when I'm reviewing a report, it's actually it's it's the first. So we call it key cellular systems or cellular systems that protect our body. And so inflammation is one of them, oxidative stress, but detox is really one of the most important. And the idea is that our body has this constant exposure to toxins from our external environment, as you just mentioned, whether it's pollution, exposure to pesticides and herbicides, fertilisers in our food, but it can also, it's also what we call endogenous, which is inside our body. Our body produces metabolites that are toxic to our body that we need to clear. And this often happens in things like hormone metabolism, where if we don't clear hormone metabolites, that can actually do damage. So we really, really want to understand how efficient am I at being able to clear these toxins. So I always talk about the person who smoked cigarettes until they were like 110, died in their sleep, never got lung cancer. How did that happen? Well, that individual was a super, super detoxifier. They were able to take that toxin, that molecule from the cigarette smoke and get it in and out of their body in such an efficient manner that it didn't have time to be able to damage, right? And then you think of other people who can get lung cancer at an early age as a passive smoker. So this is the concept of detoxification. And there's some amazing genes that we know about. The the good thing about detoxification is there's so much we can do. So we have a gene, for example, called GST, which stands for glutathione S-transferase, very powerful gene, it's actually part of a whole family. And this the job of this gene is to pick up what we call an activated toxin. So a toxin when it's at its worst, we call it an intermediate toxin, it's at its most powerful, and it conjugates it. So it it attaches a molecule that kind of inactivates it. Very clever. And when it attaches this molecule to inactivate it, it also makes it water soluble. So now our body can excrete it through our urine or through our sweat, through breathing. So super clever, clever group of genes. The problem is there are some spelling changes which cause problems with these GST genes. And in some cases, it actually deletes the gene. So we're not only don't have a gene that's working, remember I said like switching off the, right? This is like the extreme of switching off, it deletes it. We don't have the enzyme functioning at all. Now, imagine we do a genetic test and we find out. Now remember, genes by themselves do not determine disease, they give us information about a metabolic process. So now we see you've got a deletion in the GST, we understand from looking your whole polygenic profile of detoxification that you're not detoxifying as optimally, you live in the centre of London, you go running every morning breathing that lovely air, what are we going to do, right? So we have to upregulate, we have to switch on your detox pathways to optimise how you manage. Well, we're going to do two things. We're going to try and reduce your exposure to toxins, that goes without saying, but we also want to increase your body's ability. Now, the amazing thing is that there are a whole lot of molecules in food that can switch on other genes that can compensate for the fact that you had the GSTM1 enzyme deleted. And one of those extraordinary foods is what we call the cruciferous vegetables, which are our broccoli and our cauliflower and our cabbage and kohlrabi and and the very famous English Brussels sprout, right? Not the overcooked Brussels sprout, the undercooked Brussels sprout. So when we eat these foods, these incredible plant foods, these incredible vegetables, they switch on genes which switch on our detoxification pathways and optimise our ability to clear toxins from our body. So that's just one amazing, when we we spoke about this concept of insights and responsiveness, and this is just one example.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, no, that's fantastic because it I think it certainly empowers the patient to have a different conversation with themselves actually as well and explain to themselves that, you know what, it's not due to lack of willpower. This is something that's actually part of my makeup and I have to manage with my environment. I mean, just that around appetite is something for me, like I know I can't keep junk food or high sugar items in the house because I will eat them because I know they're there. So that's actually helped me manage my own environment at home. And I think if it was something like in a report, that is highly, highly motivating. One thing I've heard you talk about before is this whole concept around detoxification. And I think in an environment now that is becoming increasingly polluted, I mean, I'm I'm sat here in the middle of London and there's aeroplanes, there's urban traffic, there's plastic, etc. I think this conversation is becoming a lot more important. Are there snips or snip profiles that we can look at and determine how good or bad we are at the process?

Dr Yael Joffe: Absolutely. And in fact, detoxification is probably one of the most important pathways that we look at. And when I'm reviewing a report, it's actually it's it's the first. So we call it key cellular systems or cellular systems that protect our body. And so inflammation is one of them, oxidative stress, but detox is really one of the most important. And the idea is that our body has this constant exposure to toxins from our external environment, as you just mentioned, whether it's pollution, exposure to pesticides and herbicides, fertilisers in our food, but it can also, it's also what we call endogenous, which is inside our body. Our body produces metabolites that are toxic to our body that we need to clear. And this often happens in things like hormone metabolism, where if we don't clear hormone metabolites, that can actually do damage. So we really, really want to understand how efficient am I at being able to clear these toxins. So I always talk about the person who smoked cigarettes until they were like 110, died in their sleep, never got lung cancer. How did that happen? Well, that individual was a super, super detoxifier. They were able to take that toxin, that molecule from the cigarette smoke and get it in and out of their body in such an efficient manner that it didn't have time to be able to damage, right? And then you think of other people who can get lung cancer at an early age as a passive smoker. So this is the concept of detoxification. And there's some amazing genes that we know about. The the good thing about detoxification is there's so much we can do. So we have a gene, for example, called GST, which stands for glutathione S-transferase, very powerful gene, it's actually part of a whole family. And this the job of this gene is to pick up what we call an activated toxin. So a toxin when it's at its worst, we call it an intermediate toxin, it's at its most powerful, and it conjugates it. So it it attaches a molecule that kind of inactivates it. Very clever. And when it attaches this molecule to inactivate it, it also makes it water soluble. So now our body can excrete it through our urine or through our sweat, through breathing. So super clever, clever group of genes. The problem is there are some spelling changes which cause problems with these GST genes. And in some cases, it actually deletes the gene. So we're not only don't have a gene that's working, remember I said like switching off the, right? This is like the extreme of switching off, it deletes it. We don't have the enzyme functioning at all. Now, imagine we do a genetic test and we find out. Now remember, genes by themselves do not determine disease, they give us information about a metabolic process. So now we see you've got a deletion in the GST, we understand from looking your whole polygenic profile of detoxification that you're not detoxifying as optimally, you live in the centre of London, you go running every morning breathing that lovely air, what are we going to do, right? So we have to upregulate, we have to switch on your detox pathways to optimise how you manage. Well, we're going to do two things. We're going to try and reduce your exposure to toxins, that goes without saying, but we also want to increase your body's ability. Now, the amazing thing is that there are a whole lot of molecules in food that can switch on other genes that can compensate for the fact that you had the GSTM1 enzyme deleted. And one of those extraordinary foods is what we call the cruciferous vegetables, which are our broccoli and our cauliflower and our cabbage and kohlrabi and and the very famous English Brussels sprout, right? Not the overcooked Brussels sprout, the undercooked Brussels sprout. So when we eat these foods, these incredible plant foods, these incredible vegetables, they switch on genes which switch on our detoxification pathways and optimise our ability to clear toxins from our body. So that's just one amazing, when we we spoke about this concept of insights and responsiveness, and this is just one example.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, no, that's fantastic because it I think it certainly empowers the patient to have a different conversation with themselves actually as well and explain to themselves that, you know what, it's not due to lack of willpower. This is something that's actually part of my makeup and I have to manage with my environment. I mean, just that around appetite is something for me, like I know I can't keep junk food or high sugar items in the house because I will eat them because I know they're there. So that's actually helped me manage my own environment at home. And I think if it was something like in a report, that is highly, highly motivating. One thing I've heard you talk about before is this whole concept around detoxification. And I think in an environment now that is becoming increasingly polluted, I mean, I'm I'm sat here in the middle of London and there's aeroplanes, there's urban traffic, there's plastic, etc. I think this conversation is becoming a lot more important. Are there snips or snip profiles that we can look at and determine how good or bad we are at the process?

Dr Yael Joffe: Absolutely. And in fact, detoxification is probably one of the most important pathways that we look at. And when I'm reviewing a report, it's actually it's it's the first. So we call it key cellular systems or cellular systems that protect our body. And so inflammation is one of them, oxidative stress, but detox is really one of the most important. And the idea is that our body has this constant exposure to toxins from our external environment, as you just mentioned, whether it's pollution, exposure to pesticides and herbicides, fertilisers in our food, but it can also, it's also what we call endogenous, which is inside our body. Our body produces metabolites that are toxic to our body that we need to clear. And this often happens in things like hormone metabolism, where if we don't clear hormone metabolites, that can actually do damage. So we really, really want to understand how efficient am I at being able to clear these toxins. So I always talk about the person who smoked cigarettes until they were like 110, died in their sleep, never got lung cancer. How did that happen? Well, that individual was a super, super detoxifier. They were able to take that toxin, that molecule from the cigarette smoke and get it in and out of their body in such an efficient manner that it didn't have time to be able to damage, right? And then you think of other people who can get lung cancer at an early age as a passive smoker. So this is the concept of detoxification. And there's some amazing genes that we know about. The the good thing about detoxification is there's so much we can do. So we have a gene, for example, called GST, which stands for glutathione S-transferase, very powerful gene, it's actually part of a whole family. And this the job of this gene is to pick up what we call an activated toxin. So a toxin when it's at its worst, we call it an intermediate toxin, it's at its most powerful, and it conjugates it. So it it attaches a molecule that kind of inactivates it. Very clever. And when it attaches this molecule to inactivate it, it also makes it water soluble. So now our body can excrete it through our urine or through our sweat, through breathing. So super clever, clever group of genes. The problem is there are some spelling changes which cause problems with these GST genes. And in some cases, it actually deletes the gene. So we're not only don't have a gene that's working, remember I said like switching off the, right? This is like the extreme of switching off, it deletes it. We don't have the enzyme functioning at all. Now, imagine we do a genetic test and we find out. Now remember, genes by themselves do not determine disease, they give us information about a metabolic process. So now we see you've got a deletion in the GST, we understand from looking your whole polygenic profile of detoxification that you're not detoxifying as optimally, you live in the centre of London, you go running every morning breathing that lovely air, what are we going to do, right? So we have to upregulate, we have to switch on your detox pathways to optimise how you manage. Well, we're going to do two things. We're going to try and reduce your exposure to toxins, that goes without saying, but we also want to increase your body's ability. Now, the amazing thing is that there are a whole lot of molecules in food that can switch on other genes that can compensate for the fact that you had the GSTM1 enzyme deleted. And one of those extraordinary foods is what we call the cruciferous vegetables, which are our broccoli and our cauliflower and our cabbage and kohlrabi and and the very famous English Brussels sprout, right? Not the overcooked Brussels sprout, the undercooked Brussels sprout. So when we eat these foods, these incredible plant foods, these incredible vegetables, they switch on genes which switch on our detoxification pathways and optimise our ability to clear toxins from our body. So that's just one amazing, when we we spoke about this concept of insights and responsiveness, and this is just one example.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, no, that's fantastic because it I think it certainly empowers the patient to have a different conversation with themselves actually as well and explain to themselves that, you know what, it's not due to lack of willpower. This is something that's actually part of my makeup and I have to manage with my environment. I mean, just that around appetite is something for me, like I know I can't keep junk food or high sugar items in the house because I will eat them because I know they're there. So that's actually helped me manage my own environment at home. And I think if it was something like in a report, that is highly, highly motivating. One thing I've heard you talk about before is this whole concept around detoxification. And I think in an environment now that is becoming increasingly polluted, I mean, I'm I'm sat here in the middle of London and there's aeroplanes, there's urban traffic, there's plastic, etc. I think this conversation is becoming a lot more important. Are there snips or snip profiles that we can look at and determine how good or bad we are at the process?

Dr Yael Joffe: Absolutely. And in fact, detoxification is probably one of the most important pathways that we look at. And when I'm reviewing a report, it's actually it's it's the first. So we call it key cellular systems or cellular systems that protect our body. And so inflammation is one of them, oxidative stress, but detox is really one of the most important. And the idea is that our body has this constant exposure to toxins from our external environment, as you just mentioned, whether it's pollution, exposure to pesticides and herbicides, fertilisers in our food, but it can also, it's also what we call endogenous, which is inside our body. Our body produces metabolites that are toxic to our body that we need to clear. And this often happens in things like hormone metabolism, where if we don't clear hormone metabolites, that can actually do damage. So we really, really want to understand how efficient am I at being able to clear these toxins. So I always talk about the person who smoked cigarettes until they were like 110, died in their sleep, never got lung cancer. How did that happen? Well, that individual was a super, super detoxifier. They were able to take that toxin, that molecule from the cigarette smoke and get it in and out of their body in such an efficient manner that it didn't have time to be able to damage, right? And then you think of other people who can get lung cancer at an early age as a passive smoker. So this is the concept of detoxification. And there's some amazing genes that we know about. The the good thing about detoxification is there's so much we can do. So we have a gene, for example, called GST, which stands for glutathione S-transferase, very powerful gene, it's actually part of a whole family. And this the job of this gene is to pick up what we call an activated toxin. So a toxin when it's at its worst, we call it an intermediate toxin, it's at its most powerful, and it conjugates it. So it it attaches a molecule that kind of inactivates it. Very clever. And when it attaches this molecule to inactivate it, it also makes it water soluble. So now our body can excrete it through our urine or through our sweat, through breathing. So super clever, clever group of genes. The problem is there are some spelling changes which cause problems with these GST genes. And in some cases, it actually deletes the gene. So we're not only don't have a gene that's working, remember I said like switching off the, right? This is like the extreme of switching off, it deletes it. We don't have the enzyme functioning at all. Now, imagine we do a genetic test and we find out. Now remember, genes by themselves do not determine disease, they give us information about a metabolic process. So now we see you've got a deletion in the GST, we understand from looking your whole polygenic profile of detoxification that you're not detoxifying as optimally, you live in the centre of London, you go running every morning breathing that lovely air, what are we going to do, right? So we have to upregulate, we have to switch on your detox pathways to optimise how you manage. Well, we're going to do two things. We're going to try and reduce your exposure to toxins, that goes without saying, but we also want to increase your body's ability. Now, the amazing thing is that there are a whole lot of molecules in food that can switch on other genes that can compensate for the fact that you had the GSTM1 enzyme deleted. And one of those extraordinary foods is what we call the cruciferous vegetables, which are our broccoli and our cauliflower and our cabbage and kohlrabi and and the very famous English Brussels sprout, right? Not the overcooked Brussels sprout, the undercooked Brussels sprout. So when we eat these foods, these incredible plant foods, these incredible vegetables, they switch on genes which switch on our detoxification pathways and optimise our ability to clear toxins from our body. So that's just one amazing, when we we spoke about this concept of insights and responsiveness, and this is just one example.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, no, that's fantastic because it I think it certainly empowers the patient to have a different conversation with themselves actually as well and explain to themselves that, you know what, it's not due to lack of willpower. This is something that's actually part of my makeup and I have to manage with my environment. I mean, just that around appetite is something for me, like I know I can't keep junk food or high sugar items in the house because I will eat them because I know they're there. So that's actually helped me manage my own environment at home. And I think if it was something like in a report, that is highly, highly motivating. One thing I've heard you talk about before is this whole concept around detoxification. And I think in an environment now that is becoming increasingly polluted, I mean, I'm I'm sat here in the middle of London and there's aeroplanes, there's urban traffic, there's plastic, etc. I think this conversation is becoming a lot more important. Are there snips or snip profiles that we can look at and determine how good or bad we are at the process?

Dr Yael Joffe: Absolutely. And in fact, detoxification is probably one of the most important pathways that we look at. And when I'm reviewing a report, it's actually it's it's the first. So we call it key cellular systems or cellular systems that protect our body. And so inflammation is one of them, oxidative stress, but detox is really one of the most important. And the idea is that our body has this constant exposure to toxins from our external environment, as you just mentioned, whether it's pollution, exposure to pesticides and herbicides, fertilisers in our food, but it can also, it's also what we call endogenous, which is inside our body. Our body produces metabolites that are toxic to our body that we need to clear. And this often happens in things like hormone metabolism, where if we don't clear hormone metabolites, that can actually do damage. So we really, really want to understand how efficient am I at being able to clear these toxins. So I always talk about the person who smoked cigarettes until they were like 110, died in their sleep, never got lung cancer. How did that happen? Well, that individual was a super, super detoxifier. They were able to take that toxin, that molecule from the cigarette smoke and get it in and out of their body in such an efficient manner that it didn't have time to be able to damage, right? And then you think of other people who can get lung cancer at an early age as a passive smoker. So this is the concept of detoxification. And there's some amazing genes that we know about. The the good thing about detoxification is there's so much we can do. So we have a gene, for example, called GST, which stands for glutathione S-transferase, very powerful gene, it's actually part of a whole family. And this the job of this gene is to pick up what we call an activated toxin. So a toxin when it's at its worst, we call it an intermediate toxin, it's at its most powerful, and it conjugates it. So it it attaches a molecule that kind of inactivates it. Very clever. And when it attaches this molecule to inactivate it, it also makes it water soluble. So now our body can excrete it through our urine or through our sweat, through breathing. So super clever, clever group of genes. The problem is there are some spelling changes which cause problems with these GST genes. And in some cases, it actually deletes the gene. So we're not only don't have a gene that's working, remember I said like switching off the, right? This is like the extreme of switching off, it deletes it. We don't have the enzyme functioning at all. Now, imagine we do a genetic test and we find out. Now remember, genes by themselves do not determine disease, they give us information about a metabolic process. So now we see you've got a deletion in the GST, we understand from looking your whole polygenic profile of detoxification that you're not detoxifying as optimally, you live in the centre of London, you go running every morning breathing that lovely air, what are we going to do, right? So we have to upregulate, we have to switch on your detox pathways to optimise how you manage. Well, we're going to do two things. We're going to try and reduce your exposure to toxins, that goes without saying, but we also want to increase your body's ability. Now, the amazing thing is that there are a whole lot of molecules in food that can switch on other genes that can compensate for the fact that you had the GSTM1 enzyme deleted. And one of those extraordinary foods is what we call the cruciferous vegetables, which are our broccoli and our cauliflower and our cabbage and kohlrabi and and the very famous English Brussels sprout, right? Not the overcooked Brussels sprout, the undercooked Brussels sprout. So when we eat these foods, these incredible plant foods, these incredible vegetables, they switch on genes which switch on our detoxification pathways and optimise our ability to clear toxins from our body. So that's just one amazing, when we we spoke about this concept of insights and responsiveness, and this is just one example.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, no, that's fantastic because it I think it certainly empowers the patient to have a different conversation with themselves actually as well and explain to themselves that, you know what, it's not due to lack of willpower. This is something that's actually part of my makeup and I have to manage with my environment. I mean, just that around appetite is something for me, like I know I can't keep junk food or high sugar items in the house because I will eat them because I know they're there. So that's actually helped me manage my own environment at home. And I think if it was something like in a report, that is highly, highly motivating. One thing I've heard you talk about before is this whole concept around detoxification. And I think in an environment now that is becoming increasingly polluted, I mean, I'm I'm sat here in the middle of London and there's aeroplanes, there's urban traffic, there's plastic, etc. I think this conversation is becoming a lot more important. Are there snips or snip profiles that we can look at and determine how good or bad we are at the process?

Dr Yael Joffe: Absolutely. And in fact, detoxification is probably one of the most important pathways that we look at. And when I'm reviewing a report, it's actually it's it's the first. So we call it key cellular systems or cellular systems that protect our body. And so inflammation is one of them, oxidative stress, but detox is really one of the most important. And the idea is that our body has this constant exposure to toxins from our external environment, as you just mentioned, whether it's pollution, exposure to pesticides and herbicides, fertilisers in our food, but it can also, it's also what we call endogenous, which is inside our body. Our body produces metabolites that are toxic to our body that we need to clear. And this often happens in things like hormone metabolism, where if we don't clear hormone metabolites, that can actually do damage. So we really, really want to understand how efficient am I at being able to clear these toxins. So I always talk about the person who smoked cigarettes until they were like 110, died in their sleep, never got lung cancer. How did that happen? Well, that individual was a super, super detoxifier. They were able to take that toxin, that molecule from the cigarette smoke and get it in and out of their body in such an efficient manner that it didn't have time to be able to damage, right? And then you think of other people who can get lung cancer at an early age as a passive smoker. So this is the concept of detoxification. And there's some amazing genes that we know about. The the good thing about detoxification is there's so much we can do. So we have a gene, for example, called GST, which stands for glutathione S-transferase, very powerful gene, it's actually part of a whole family. And this the job of this gene is to pick up what we call an activated toxin. So a toxin when it's at its worst, we call it an intermediate toxin, it's at its most powerful, and it conjugates it. So it it attaches a molecule that kind of inactivates it. Very clever. And when it attaches this molecule to inactivate it, it also makes it water soluble. So now our body can excrete it through our urine or through our sweat, through breathing. So super clever, clever group of genes. The problem is there are some spelling changes which cause problems with these GST genes. And in some cases, it actually deletes the gene. So we're not only don't have a gene that's working, remember I said like switching off the, right? This is like the extreme of switching off, it deletes it. We don't have the enzyme functioning at all. Now, imagine we do a genetic test and we find out. Now remember, genes by themselves do not determine disease, they give us information about a metabolic process. So now we see you've got a deletion in the GST, we understand from looking your whole polygenic profile of detoxification that you're not detoxifying as optimally, you live in the centre of London, you go running every morning breathing that lovely air, what are we going to do, right? So we have to upregulate, we have to switch on your detox pathways to optimise how you manage. Well, we're going to do two things. We're going to try and reduce your exposure to toxins, that goes without saying, but we also want to increase your body's ability. Now, the amazing thing is that there are a whole lot of molecules in food that can switch on other genes that can compensate for the fact that you had the GSTM1 enzyme deleted. And one of those extraordinary foods is what we call the cruciferous vegetables, which are our broccoli and our cauliflower and our cabbage and kohlrabi and and the very famous English Brussels sprout, right? Not the overcooked Brussels sprout, the undercooked Brussels sprout. So when we eat these foods, these incredible plant foods, these incredible vegetables, they switch on genes which switch on our detoxification pathways and optimise our ability to clear toxins from our body. So that's just one amazing, when we we spoke about this concept of insights and responsiveness, and this is just one example.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, no, that's fantastic because it I think it certainly empowers the patient to have a different conversation with themselves actually as well and explain to themselves that, you know what, it's not due to lack of willpower. This is something that's actually part of my makeup and I have to manage with my environment. I mean, just that around appetite is something for me, like I know I can't keep junk food or high sugar items in the house because I will eat them because I know they're there. So that's actually helped me manage my own environment at home. And I think if it was something like in a report, that is highly, highly motivating. One thing I've heard you talk about before is this whole concept around detoxification. And I think in an environment now that is becoming increasingly polluted, I mean, I'm I'm sat here in the middle of London and there's aeroplanes, there's urban traffic, there's plastic, etc. I think this conversation is becoming a lot more important. Are there snips or snip profiles that we can look at and determine how good or bad we are at the process?

Dr Yael Joffe: Absolutely. And in fact, detoxification is probably one of the most important pathways that we look at. And when I'm reviewing a report, it's actually it's it's the first. So we call it key cellular systems or cellular systems that protect our body. And so inflammation is one of them, oxidative stress, but detox is really one of the most important. And the idea is that our body has this constant exposure to toxins from our external environment, as you just mentioned, whether it's pollution, exposure to pesticides and herbicides, fertilisers in our food, but it can also, it's also what we call endogenous, which is inside our body. Our body produces metabolites that are toxic to our body that we need to clear. And this often happens in things like hormone metabolism, where if we don't clear hormone metabolites, that can actually do damage. So we really, really want to understand how efficient am I at being able to clear these toxins. So I always talk about the person who smoked cigarettes until they were like 110, died in their sleep, never got lung cancer. How did that happen? Well, that individual was a super, super detoxifier. They were able to take that toxin, that molecule from the cigarette smoke and get it in and out of their body in such an efficient manner that it didn't have time to be able to damage, right? And then you think of other people who can get lung cancer at an early age as a passive smoker. So this is the concept of detoxification. And there's some amazing genes that we know about. The the good thing about detoxification is there's so much we can do. So we have a gene, for example, called GST, which stands for glutathione S-transferase, very powerful gene, it's actually part of a whole family. And this the job of this gene is to pick up what we call an activated toxin. So a toxin when it's at its worst, we call it an intermediate toxin, it's at its most powerful, and it conjugates it. So it it attaches a molecule that kind of inactivates it. Very clever. And when it attaches this molecule to inactivate it, it also makes it water soluble. So now our body can excrete it through our urine or through our sweat, through breathing. So super clever, clever group of genes. The problem is there are some spelling changes which cause problems with these GST genes. And in some cases, it actually deletes the gene. So we're not only don't have a gene that's working, remember I said like switching off the, right? This is like the extreme of switching off, it deletes it. We don't have the enzyme functioning at all. Now, imagine we do a genetic test and we find out. Now remember, genes by themselves do not determine disease, they give us information about a metabolic process. So now we see you've got a deletion in the GST, we understand from looking your whole polygenic profile of detoxification that you're not detoxifying as optimally, you live in the centre of London, you go running every morning breathing that lovely air, what are we going to do, right? So we have to upregulate, we have to switch on your detox pathways to optimise how you manage. Well, we're going to do two things. We're going to try and reduce your exposure to toxins, that goes without saying, but we also want to increase your body's ability. Now, the amazing thing is that there are a whole lot of molecules in food that can switch on other genes that can compensate for the fact that you had the GSTM1 enzyme deleted. And one of those extraordinary foods is what we call the cruciferous vegetables, which are our broccoli and our cauliflower and our cabbage and kohlrabi and and the very famous English Brussels sprout, right? Not the overcooked Brussels sprout, the undercooked Brussels sprout. So when we eat these foods, these incredible plant foods, these incredible vegetables, they switch on genes which switch on our detoxification pathways and optimise our ability to clear toxins from our body. So that's just one amazing, when we we spoke about this concept of insights and responsiveness, and this is just one example.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, no, that's fantastic because it I think it certainly empowers the patient to have a different conversation with themselves actually as well and explain to themselves that, you know what, it's not due to lack of willpower. This is something that's actually part of my makeup and I have to manage with my environment. I mean, just that around appetite is something for me, like I know I can't keep junk food or high sugar items in the house because I will eat them because I know they're there. So that's actually helped me manage my own environment at home. And I think if it was something like in a report, that is highly, highly motivating. One thing I've heard you talk about before is this whole concept around detoxification. And I think in an environment now that is becoming increasingly polluted, I mean, I'm I'm sat here in the middle of London and there's aeroplanes, there's urban traffic, there's plastic, etc. I think this conversation is becoming a lot more important. Are there snips or snip profiles that we can look at and determine how good or bad we are at the process?

Dr Yael Joffe: Absolutely. And in fact, detoxification is probably one of the most important pathways that we look at. And when I'm reviewing a report, it's actually it's it's the first. So we call it key cellular systems or cellular systems that protect our body. And so inflammation is one of them, oxidative stress, but detox is really one of the most important. And the idea is that our body has this constant exposure to toxins from our external environment, as you just mentioned, whether it's pollution, exposure to pesticides and herbicides, fertilisers in our food, but it can also, it's also what we call endogenous, which is inside our body. Our body produces metabolites that are toxic to our body that we need to clear. And this often happens in things like hormone metabolism, where if we don't clear hormone metabolites, that can actually do damage. So we really, really want to understand how efficient am I at being able to clear these toxins. So I always talk about the person who smoked cigarettes until they were like 110, died in their sleep, never got lung cancer. How did that happen? Well, that individual was a super, super detoxifier. They were able to take that toxin, that molecule from the cigarette smoke and get it in and out of their body in such an efficient manner that it didn't have time to be able to damage, right? And then you think of other people who can get lung cancer at an early age as a passive smoker. So this is the concept of detoxification. And there's some amazing genes that we know about. The the good thing about detoxification is there's so much we can do. So we have a gene, for example, called GST, which stands for glutathione S-transferase, very powerful gene, it's actually part of a whole family. And this the job of this gene is to pick up what we call an activated toxin. So a toxin when it's at its worst, we call it an intermediate toxin, it's at its most powerful, and it conjugates it. So it it attaches a molecule that kind of inactivates it. Very clever. And when it attaches this molecule to inactivate it, it also makes it water soluble. So now our body can excrete it through our urine or through our sweat, through breathing. So super clever, clever group of genes. The problem is there are some spelling changes which cause problems with these GST genes. And in some cases, it actually deletes the gene. So we're not only don't have a gene that's working, remember I said like switching off the, right? This is like the extreme of switching off, it deletes it. We don't have the enzyme functioning at all. Now, imagine we do a genetic test and we find out. Now remember, genes by themselves do not determine disease, they give us information about a metabolic process. So now we see you've got a deletion in the GST, we understand from looking your whole polygenic profile of detoxification that you're not detoxifying as optimally, you live in the centre of London, you go running every morning breathing that lovely air, what are we going to do, right? So we have to upregulate, we have to switch on your detox pathways to optimise how you manage. Well, we're going to do two things. We're going to try and reduce your exposure to toxins, that goes without saying, but we also want to increase your body's ability. Now, the amazing thing is that there are a whole lot of molecules in food that can switch on other genes that can compensate for the fact that you had the GSTM1 enzyme deleted. And one of those extraordinary foods is what we call the cruciferous vegetables, which are our broccoli and our cauliflower and our cabbage and kohlrabi and and the very famous English Brussels sprout, right? Not the overcooked Brussels sprout, the undercooked Brussels sprout. So when we eat these foods, these incredible plant foods, these incredible vegetables, they switch on genes which switch on our detoxification pathways and optimise our ability to clear toxins from our body. So that's just one amazing, when we we spoke about this concept of insights and responsiveness, and this is just one example.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, no, that's fantastic because it I think it certainly empowers the patient to have a different conversation with themselves actually as well and explain to themselves that, you know what, it's not due to lack of willpower. This is something that's actually part of my makeup and I have to manage with my environment. I mean, just that around appetite is something for me, like I know I can't keep junk food or high sugar items in the house because I will eat them because I know they're there. So that's actually helped me manage my own environment at home. And I think if it was something like in a report, that is highly, highly motivating. One thing I've heard you talk about before is this whole concept around detoxification. And I think in an environment now that is becoming increasingly polluted, I mean, I'm I'm sat here in the middle of London and there's aeroplanes, there's urban traffic, there's plastic, etc. I think this conversation is becoming a lot more important. Are there snips or snip profiles that we can look at and determine how good or bad we are at the process?

Dr Yael Joffe: Absolutely. And in fact, detoxification is probably one of the most important pathways that we look at. And when I'm reviewing a report, it's actually it's it's the first. So we call it key cellular systems or cellular systems that protect our body. And so inflammation is one of them, oxidative stress, but detox is really one of the most important. And the idea is that our body has this constant exposure to toxins from our external environment, as you just mentioned, whether it's pollution, exposure to pesticides and herbicides, fertilisers in our food, but it can also, it's also what we call endogenous, which is inside our body. Our body produces metabolites that are toxic to our body that we need to clear. And this often happens in things like hormone metabolism, where if we don't clear hormone metabolites, that can actually do damage. So we really, really want to understand how efficient am I at being able to clear these toxins. So I always talk about the person who smoked cigarettes until they were like 110, died in their sleep, never got lung cancer. How did that happen? Well, that individual was a super, super detoxifier. They were able to take that toxin, that molecule from the cigarette smoke and get it in and out of their body in such an efficient manner that it didn't have time to be able to damage, right? And then you think of other people who can get lung cancer at an early age as a passive smoker. So this is the concept of detoxification. And there's some amazing genes that we know about. The the good thing about detoxification is there's so much we can do. So we have a gene, for example, called GST, which stands for glutathione S-transferase, very powerful gene, it's actually part of a whole family. And this the job of this gene is to pick up what we call an activated toxin. So a toxin when it's at its worst, we call it an intermediate toxin, it's at its most powerful, and it conjugates it. So it it attaches a molecule that kind of inactivates it. Very clever. And when it attaches this molecule to inactivate it, it also makes it water soluble. So now our body can excrete it through our urine or through our sweat, through breathing. So super clever, clever group of genes. The problem is there are some spelling changes which cause problems with these GST genes. And in some cases, it actually deletes the gene. So we're not only don't have a gene that's working, remember I said like switching off the, right? This is like the extreme of switching off, it deletes it. We don't have the enzyme functioning at all. Now, imagine we do a genetic test and we find out. Now remember, genes by themselves do not determine disease, they give us information about a metabolic process. So now we see you've got a deletion in the GST, we understand from looking your whole polygenic profile of detoxification that you're not detoxifying as optimally, you live in the centre of London, you go running every morning breathing that lovely air, what are we going to do, right? So we have to upregulate, we have to switch on your detox pathways to optimise how you manage. Well, we're going to do two things. We're going to try and reduce your exposure to toxins, that goes without saying, but we also want to increase your body's ability. Now, the amazing thing is that there are a whole lot of molecules in food that can switch on other genes that can compensate for the fact that you had the GSTM1 enzyme deleted. And one of those extraordinary foods is what we call the cruciferous vegetables, which are our broccoli and our cauliflower and our cabbage and kohlrabi and and the very famous English Brussels sprout, right? Not the overcooked Brussels sprout, the undercooked Brussels sprout. So when we eat these foods, these incredible plant foods, these incredible vegetables, they switch on genes which switch on our detoxification pathways and optimise our ability to clear toxins from our body. So that's just one amazing, when we we spoke about this concept of insights and responsiveness, and this is just one example.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, no, that's fantastic because it I think it certainly empowers the patient to have a different conversation with themselves actually as well and explain to themselves that, you know what, it's not due to lack of willpower. This is something that's actually part of my makeup and I have to manage with my environment. I mean, just that around appetite is something for me, like I know I can't keep junk food or high sugar items in the house because I will eat them because I know they're there. So that's actually helped me manage my own environment at home. And I think if it was something like in a report, that is highly, highly motivating. One thing I've heard you talk about before is this whole concept around detoxification. And I think in an environment now that is becoming increasingly polluted, I mean, I'm I'm sat here in the middle of London and there's aeroplanes, there's urban traffic, there's plastic, etc. I think this conversation is becoming a lot more important. Are there snips or snip profiles that we can look at and determine how good or bad we are at the process?