Professor Valter Longo: Can you just do 12 hours, and nothing else? And then they're a little bit surprised and say, that's all I got to do? For now, yes. And then B in my third book now for children, I talk about the B is like, can you just reduce your starches by 10% a day, right? And people don't realise, then we do the calculations, if you take the pasta, the rice, the bread, the potatoes, 10% down. Say, well, don't I need to get rid of it? Absolutely not. Don't I need to go low carb? Absolutely not. People on low carb diet live shorter. And it's better to be, based on the Lancet meta-analysis, it's better to be on an 80% carb diet than on a low carb diet.

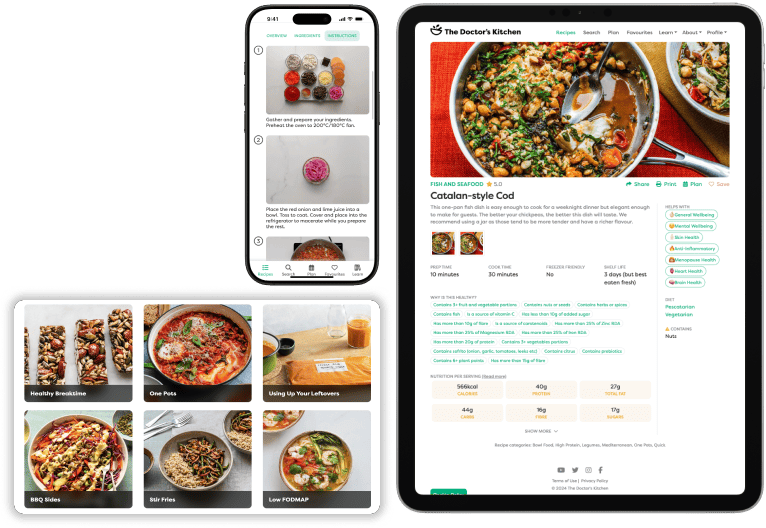

Podcast Intro: Welcome to the Doctor's Kitchen podcast, the show about food, lifestyle, medicine, and how to improve your health today. My name is Dr Rupy. I'm a medical doctor. I also study nutrition, and I'm a firm believer in the power of food and lifestyle as medicine. Join me on this podcast where we explore multiple determinants of what allows you to live your best life. And remember, you can sign up to the doctorskitchen.com for the newsletter where we give weekly recipes plus tips and hacks on how to improve your lifestyle today.

Dr Rupy: And my guest is the incredible Professor Valter Longo, an internationally recognised leader in the field of ageing studies and related diseases. His discoveries include the identification of some of the major genetic mutations that offer protection from ageing and many common diseases. He's professor of gerontology and biological science and director of the Longevity Institute at the School of Gerontology at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. And he's also director of the Laboratory of Oncology and Longevity at the Institute of Molecular Oncology, the IFOM in Milan. He is quite simply the guy when it comes to fasting at the moment, and in particular a method of fasting that he has coined fasting mimicking diet. Now, essentially that is where you drop your calorie intake to less than 500 calories per day, which is a crushingly low amount of energy per day, over a five-day period per month, or depending on how you're using this FMD diet, as it's also known, it can be once a month, it can be once every three months, or once every six months. And in his book, The Longevity Diet, he talks about the application of FMD for a number of different conditions, as well as general healthy people, and really setting out the basis by which we can all improve our lives and live healthier, happier ones as well. On this podcast, it's going to get a little bit technical, but I think this is going to be a good dive into what we mean by fasting. At the start, we talk about the different types of fasting, alternate day fasting, time-restricted feeding. It's something I get asked a lot about, and I thought I'd dedicate an entire episode to this whole subject with one of the world-leading experts. He really is, and if you're a fan of fasting or the fan of the research at least, then you'll definitely know who Professor Valter Longo is. We talk about the mechanisms of actions behind fasting, something that has been an evolutionary adaptation. We would not have survived if we did not go thrive through periods where we did not have access to nutrition. And so there are certain genes that have allowed us to adapt to quite troublesome environments. The trouble is, we are now exposed to food environments 24/7. The opportunity of eating is all over us, and we essentially indulge overeating for one, but also eating outside of a normal eating window, which is something that we talk about too. After talking about the mechanisms, we talk about the utility of it. Now, you'd immediately think of obesity, metabolic syndrome, perhaps type two diabetes, but actually it extends to autoimmune conditions like type one diabetes, as well as MS or multiple sclerosis, and also cancer. Now, this is a tricky subject to talk about considering the lack of research, but this is a lot of it is theoretical, but actually there are some small-scale human trials that this year may change the way we look at how we feed patients whilst on therapy such as chemotherapy and immunotherapy as well, the novel immunotherapies that we have access to and have been game-changing for oncology. Apart from the mechanisms and the different uses, we talk a little bit about Professor Valter himself. He's Italian, as you can tell from his accent. He's a lover of food, a lover of music, and he certainly eats the same way that I eat, which is largely plant-based with small amounts of animal protein. He's pescatarian himself. And just getting to chat to him was an absolute pleasure. He can talk, and it was great to just let him talk and just listen to him. And I will certainly link to some of the papers and the book, The Longevity Diet, on the podcast show notes. The last thing I want to say is, this is purely intended for information purposes only. This isn't a recommendation that anyone should practice fasting. And particularly, if you do have any medical issues, this is something that you should not do without supervision from a medical professional who's comfortable with different fasting regimes or a registered dietitian or nutritionist. So please do take this with caution. This isn't a massive advert for fasting. And in particular, as we talk about water fasting and the potential dangers of that that we talk about in the podcast, this isn't for everyone. We don't know exactly which type of fasting, what dose of fasting is appropriate for what person, but certainly there is definitely scope to look into the subject a bit more and it warrants more attention in my opinion. So please do take that as a warning. This isn't an advert for fasting. And certainly if you have an unhealthy relationship with food, I wouldn't advocate fasting at all. So, without further ado, I'll stop waffling on and I'll let you enjoy our conversation with Professor Valter Longo. The podcast show notes will give you a bit more information and please do subscribe to the newsletter at thedoctorskitchen.com. We give you science-based recipes every single week, plus lots more to help you live healthier, happier lives.

Dr Rupy: I'd love to know a bit about your background, Valter, and how you eat, because generally what we do with the podcast is we get you here into the kitchen, we cook for you, we have a conversation over food, we have a break, and then we we start the podcast. So obviously we can't do that today because there's a pandemic going on and you're like 11 hours flight away. But yeah, tell me a bit about how you eat generally.

Professor Valter Longo: I eat pretty much like what I have in the book, which is mostly a vegan, but pescatarian. So vegan plus fish. And lately it's also, I would say vegetarian plus fish. So I do have some eggs every week, just very little milk-based products. And then the rest of it is, I try to, my typical dish is something that will have, let's say a little bit of pasta, maybe 60, 70 grams, and then 300 grams of of legumes and another 200 grams of mixed vegetables. That's something that I might have three or four times a week. So I try to combine, you know, understanding all the people that we follow, understanding the compliance issues, and try to make it very similar to what they're used to. So having, keeping the same components, but at the same time, you know, switching to something that scientifically and based on epidemiological studies, etc, can work. So, so yeah, that's that's the strategy. And I use, as I as I preach in the book, I use the skipping lunch or having a very small like vegan-based snack for lunch as a way to to regulate my weight. And it's been working very well and of course I've been using it for lots of people. So, let's say that last week I was a couple of pounds over, I, you know, then I skip lunch for about a week. And that goes, in fact, I go a little bit underweight. And that's exactly what I want, you know, to keep it pretty steady. So I don't I don't have up and downs because they're not so good. I usually, you know, maybe weigh myself every two, three, four days. And so I can always keep it very steady.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, I mean, that sounds really similar to how I eat myself. I'm largely plant-based. I have a lot of lentils, legumes, chickpeas, beans, pulses. And I love the in the intro to your book, you talk about the different the five pillars behind how you came up with what is a good strategy for general healthy eating, looking at epidemiological research and looking at the mechanisms as well. And yeah, that definitely sounds like a delicious way of eating too, and one that is quite achievable for a lot of people.

Professor Valter Longo: Yeah, so that's key, right? Lots of the things that we that many come up with, I remember always my my mentor at UCLA back in the early 90s, he was a Roy Walford, he was a guru of longevity. But he was coming up with these dishes that were raw vegan and and I I always looked at it and I thought, there's no way I'm eating that for more than a couple of times a year. And I I just thought that to really make it worldwide, we have to come up with things that are much more reasonable for people. Otherwise, you have like a beautiful idea that nobody implements. And provided that the the vegan the the raw vegan diet is in fact superior, which it doesn't seem to be. But so I think yeah, yeah, so trying to optimize the the the content in a scientific way, but also in a in a way that for most people be pretty straightforward to do, you know. So, so for example, you know, you could do the same thing I described without the pasta, and and yes, of course, you're going to have less starches in there. But to most people, they'll do it a number of times and eventually they'll abandon it. And and if you have the pasta in there, then that's a that's something that keeps somebody more attached to it. And and eventually they'll incorporate it and it becomes a dish that they they eat all the time.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, that that resonates really well with me because I think one of the things a lot of people don't recognise is the accessibility and the maintenance of a way of eating for a long period of time. And if you look at the length of time people actually stick to or comply with a way of eating, that's going to be the biggest sort of indicator as to the the improvement in health outcomes long term. So I really do recognise that in the book as well. It just it just sounds very achievable to, you know, skip a few meals, have a defined eating window, and and learn a bit about the science behind why that could be impactful too.

Professor Valter Longo: Yeah, and that's the one you just mentioned, it's another one of the big ones. It made the difference to lots of people that I follow and myself, you know, the 12 hours, right? So I didn't go as as Sachin Panda, many others, the 16-hour type of fasting. I think that for most people, 12 hours is is good and it's good enough and it's very safe. Now, 16 hours, as he has shown, can be much more effective, but I think that, you know, the the longer fasting periods can be used for temporary use and probably not for long-term use, both for compliance, but also for safety. And if you want later, we can discuss, you know, some of the safety issues with the longer fasting periods.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, no, that sounds brilliant. Why don't we kick off by talking about how you got into the research area around fasting and how you got into research in itself, actually? Because you you tell this wonderful story about how you saw your grandparent die and actually they lived to a ripe old age in the southern part of Italy. And that was sort of your first introduction into life and death and and health and and longevity.

Professor Valter Longo: Yeah, so yeah, I think that maybe without realising it, it wasn't something that I was thinking about all the time, but I certainly remember seeing people getting very old in Molochio. And eventually Molochio became one of the the places with the oldest centenarian prevalence in the world. And but then I thought about my my grandfather dying much earlier and I thought, how's it possible that now some of his friends are making it to 105, 107, 110, and he died a long, long time ago. So, yeah, so that that was something that was probably very central in my in my mind, even though I didn't realise it. So I was a music student and then I think I was just waiting for the opportunity to get out of music and get into what I was what I felt I had to do, which was, you know, how do you live a long life healthy? He never got that opportunity. It sounds to me like it's probably the the most important thing we got, you know, living long and healthy. And yeah, so then the first chance I had, I always tell the story, they they asked me to direct a marching band in the university and and that was my opportunity to say, I'm not going to, there's no way I'm directing a marching band. So let me let me go and do what I I I like to do, which was, you know, I switched to biochemistry and started studying aging. And interestingly, I thought about aging first and biochemistry second, because to me it was like, how do you live long and healthy? And then I thought, how do you what do you study to do that? And I thought biochemistry would be the the way to do it. So yeah, so that was um that was the beginning. And then um you know, after my undergraduate, I went to UCLA and I went to UCLA, I came to Los Angeles on purpose. Um some of it had to do with music, but most of it had to do with aging. And LA was really the the central place for for aging research, or certainly one of the the most uh focused on on the cities most focused on aging. And um and and here was both Caleb Finch at USC and Roy Walford at UCLA. And those were uh you know, I ended up doing my PhD with Roy Walford and my postdoc with Caleb Finch in neurobiology. So yeah, so that was the the coming to LA was really the um allowed me to to get together with some of the best of the best uh for for aging research. And then of course, Walford was the the the world top expert on on calorie restriction and longevity and nutrition. So, um you know, what better lab than to learn about um to begin to think about fasting. Of course, Walford was not was not fasting. It was not really talking about fasting. We're just talking about chronic calorie restriction. Um but I was lucky enough then I left Walford lab after two years and I ended up in a in a biochemistry lab where I in two biochemistry labs where I started working first on uh starvation in in bacteria and then starvation in yeast. And so yeah, so then the Walford with human calorie restriction, starvation in bacteria, starvation in yeast. I don't know why I was I was drawn towards this starvation uh um studies, but I always was and and I immediately started seeing incredible results. Like the bacteria, you starve them and they live longer and they became much stronger. And the yeast, you starve them, they and they did the same. They live about twice as long and they became resistant to all kinds of toxins. So, yeah, so then I think that that together I was set uh you know, between Walford and these two labs and um I was set to uh to focus uh lots of my career on uh on starvation responses.

Dr Rupy: And just for reference for the listeners, um Roy Walford was infamous for the biosphere experiment where I think was it two years that they lived in this isolated environment and they actually had to calorie restrict during that time?

Professor Valter Longo: Yeah, so it was two years. Uh they didn't they had to calorie restrict, yes, you're correct because it was not planned. Uh but uh Walford who was happened to be the world leading expert said, you know, why don't we, since we're running out of food, uh or we're going to run out of food, he was very clever. He said, you know, we're going to run out of food in about a year. Why don't we start uh you know, reducing the calories by about 25%? That way we'll have enough till the end. And so that was the first, as far as we know, the first human calorie restriction experiment. Um which then was followed by another um Walford student, uh Richard Weindruch, uh in monkeys, right? So my Weindruch then did another famous study in monkeys at the University of Wisconsin where they for the entire life, for 25 years, uh calorie restricted the monkeys. Um yeah, so so Walford was in Biosphere 2, he was the doctor in Biosphere 2, eight people, and they started calorie restriction. And and I mean, even though at the beginning the results were ignored, not by us, I mean, we knew all the results, but they were ignored by the medical community, but they showed truly remarkable effects, you know. So some somebody coming in with cholesterol 200 and after six months of calorie restriction, that would go to 100. And blood pressure starting let's say 120, going to 90 systolic blood pressure. Um you know, and on and on and on, fasting glucose. Now, the interesting thing was, and that's what I realised, I mean, I was there when they came out of Biosphere 2, when the crew came out, and they they looked terrible. Um and um and so, but I also started looking at the numbers and I started thinking, um you know, if somebody started with fasting glucose of 82, is it really beneficial um to get to 65 or 60 fasting glucose? Probably not, right? So, probably they were pushed to the limit and and potentially over the limit. And so I started thinking, um you know, we got to come up with something that does not have uh these potential side effects of and and burden of of chronic calorie restriction. So, I think to me that that was then 1992 access from Biosphere was very important to start thinking, we got to come up with something different because this is not it, you know, this is not going to be something that the world is going to do for the sake of having blood pressure and fasting glucose, etc, etc, in the right range.

Dr Rupy: And that's where I think there's been this explosion of different ways in which to mimic the effects of a lot of calorie restriction, which is something that isn't acceptable to a lot of people with the different modes of fasting. And I think there's a lot of confusion about what fasting is and what the differences are between intermittent fasting, alternate day fasting, uh FMD, fasting mimicking diets. Could we do a little bit of a whistle-stop tour as to all the different types and which one you think we should perhaps focus on?

Professor Valter Longo: Yes, yes. So, first of all, I always say, you know, fasting doesn't really mean anything. It's it's very similar to eating. You know, you would never say to somebody eating is good for you. Um so, fasting is the same way. So, fasting can hurt you or can can be have tremendous uh uh beneficial effects. Um and so the the major different kinds are um the uh time-restricted eating um that we just discussed a second ago. Uh and time-restricted eating is about, you know, how many hours a day you eat for. And and now, for example, in the United States, and I'm assuming in the UK is very similar, it's about 15 hours a day. So people eat for 15 hours a day. And I always suspected the reason, one of the reasons for that was this this bad idea of eat five or six meals a day, right? So somebody came up with that one. And then people say, you know, to eat six meals a day, I need 16 hours. And that's what they did, you know. So, so now, if you go um you know, certainly, I I say the 16 hours seems to be very effective. There's a number of studies on that. Um and uh and they're good for uh sleeping, um you know, improving sleeping, uh and also improving metabolic markers. So the people that do uh 16 hours of fasting, 8 hours of feeding, uh they tend to lose weight and and do much better. Um now, I recommend 12 and not 16 because and of course, 12 will make will make somebody um it'll take much longer to have the same effects. Uh but I liked much more 12. A, because it's much more reasonable. So if you tell somebody, start eating 8:00 a.m. and end by 8:00 p.m., I would say 90% of people can use that window and say, yeah, I can do that. I can do 7:00 a.m., 7:00 p.m. or 9:00 a.m., 9:00 p.m. You know, different people, different. In Spain, it probably be 9:00 a.m., 9:00 p.m. In the US, it might be 7:00, 7:00. Um and then also the side effects, you know. So, you know, gallstone formation, if you go from 10 hours of of fasting to 16, 18 hours of fasting, it doubles. And a gallbladder operation. Um and then if you look at the breakfast keepers, study after study after study shows that people that skip breakfast do worse, do worse for overall mortality, do worse for cardiovascular disease and potentially other diseases. So, I mean, you know, and in this discussion, of course, you can say, well, skipping breakfast is not equivalent to 16 hours of fasting. But I would say most people that do 16 hours skip breakfast, and that's probably the easiest way to do it. And um and so could there be other reasons why they have these problems? Yes, but uh it's not good if you start already with a negative effect, right? You should you should expect something that is positive or very positive. If you start saying, people that skip breakfast, they tend to live shorter, uh then um then it's it's it's not a good uh risk to take. So, yeah, 12 hours seems to be a very good way to go. Then there's something called alternate day fasting, eat one day, fast the other day, or eat one day normal and then have a very low calorie on the other day. Number of studies also very promising. Um I will argue uh extremely difficult for probably 99% of the world population. Um also, we don't know what the uh compliance long-term. I I will assume for most people long-term compliance is going to be very low. Uh but some people can do it, some people could benefit from it. So, you know, that's something if it works for for some people. And I would say probably my recommendation would be use it only for a while, for a couple of months, get to the where you need to get and then maybe be fairly beneficial and then move to some other strategy that we're going to talk about in a second. Then something called 5-2, uh Michelle Harvey and uh in in the UK, uh is one of the main scientists looking at that. So, two days a week of uh fasting, um and uh and Michael Mosley made made it popular, um the BBC journalist, um by doing two days a week that are not consecutive. In those two days, eat about 500 calories. Uh so, that looks very interesting. Um and uh you know, especially if the days are not consecutive, the risks are fairly low. Um there is some concern about uh sleeping pattern, you know, the the food intake and the sleeping go together. What happens when so frequently you go back and forth from eat, not eat, not eat, not eat, you know, every every third day essentially. That's one concern. The other concern that make me think, you know, having lived the the Walford attempt, uh which, you know, largely is a failed attempt in in convincing people to do it. Um so, calorie restriction, eating 25% less, why didn't it work? Well, I think that the great majority of people are not made to follow anything that is very frequent, right? So, if you tell somebody, uh you know, you got to do something once in a while, yes, they could do it. If you tell somebody, you got to do this every day, every third day, eventually most people will abandon it if it's disrupting enough, right? It doesn't mean everybody's going to abandon it, but I would say most people are going to abandon it, you know. I I have a difficult time telling people, you know, eat, drink one less coffee or or, you know, uh drink one less drink. Um so, so now if you say to somebody, every third day, you got to have just breakfast. Uh you see how, you know, if you thought about, I I always have this rule of 10 people I know, right? I I say, let me take 10 people I know and and and think about it and then propose it to them, right? So, so if I take 10 people I know and I say, would you be willing every third day to just have breakfast? I would say most of them wouldn't even respond to me. It's like, why are you even saying this? You know, what what kind of an idea is that, you know? And this is not to put down the technique because I think again, can be very beneficial because somebody could be said, look, you know, you're 40 pounds overweight, let's let's use the 5-2 uh to get you where you need to get. And then, you know, we'll come up with a different strategy for the rest of your life, you know. And and if you go back up, you know, then we you can use it again. So yeah, so it could be it could be very useful in that sense, uh but uh but it's not something I think that people um could do all the time. And then, you know, we I've been focusing, I mean, thinking very hard about um you know, how do you how do you turn this into a something that is almost like a medicine, right? And that's where the the periodic fasting and the fasting mimicking diet especially come from. Uh and so the idea was, you know, again, if I look at my 10 of my friends, uh what would they do? And and I think that the the 10 friends uh would be willing uh to do something every three or four months, um if I didn't tell them when to do it, but when whenever they're ready, whenever is the right moment. And so that's where the fasting mimicking diet comes in. And so it's uh first we started with water only fasting. We did a, this is over 10 years ago, we did the first clinical trial with cancer patients. And uh and it was a failure essentially. Why? Nobody wanted to do water only fasting. And the oncologists were very worried. Uh so it was a concern on on both sides. So then, then the US government uh gave us funds to do fasting mimicking diet. So, well, can you come up with a technology that will allow people to eat and get lots of the benefits of fasting? And that's where the FMD comes from. Um and uh yeah, so it's it's uh I think it's starting to hit all the the different requirements, uh meaning it's done uh we think people should do it on average only maybe three times a year, you know, somebody fairly healthy. Of course, if somebody who's obese and uh and had lots of other problems, the doctor can decide to make it much more frequently. But uh on average, I would say three or four times a year. And uh and it comes in a box and and people don't have to worry about it. It's standardized. Uh it's shown now, I don't know, maybe a couple hundred thousand people have done it. Uh it's very safe. We're about to publish a survey from 400 doctors reporting on 4,000 people, 4,000 patients. Uh yeah, so I think that I always thought if we have to, you know, spending lots of time, we now have, you know, 25 clinical trials running, spending lots of time with physicians, I always thought, I I I understand, I I it took me a while to understand them, but um um but I always thought, uh you know, I I see what they want. I see what would uh what they would feel this is uh reasonable and I am willing to consider it. Um and yeah, and reasonable to them was clinically tested, multiple trials, uh standardized, uh safety record, etc, etc. Yeah, so that's what we worked very hard. And you know, after, you know, 25 years or whatever, I think we're there, uh at least with this um and we'll see what happens. But um but uh I I I really like this uh possibility for the physician to have this in the toolkit and say, okay, yeah, I could put you're starting to become overweight and insulin resistant, etc, etc. I'm going to put you on three cycles of this FMD and uh see what happens and and see if we can keep you off drugs. Um you know, and if it fails, then there's a possibility of combining it with drugs, um or, you know, just just do drugs. But I but I think that the key of the FMD is uh really trying to reset the body. Um you know, these five days have the purpose of reset a lot of the issues that may be or the problems that and and junk that may be accumulating in cells and in the body. And junk can also be in the form of cells, a bad cell, right? So, an autoimmune cell is a bad cell, a pre-cancerous cell is a bad cell, a cancer cell is a bad cell. So, it it it makes sense. I always say, you know, if you cut yourself, um you have a repair in within a week or so, you cannot even see the cut. And so, is it possible that in the inside of the body, we have no repair system? And and then the question is, well, it it clearly doesn't just go on on its own when you become insulin resistant or when you start developing cancerous cells. So, could it be the fasting represented that moment where you you check everything and and and get rid of everything that is damaged and then replace it with uh with components that are not damaged.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, I definitely want to get into some of the mechanisms, but I I I do want to uh say that I I agree with the standardization of how we do nutritional research because this is something that's lacking, I think, within the nutritional world. We don't have a set way of testing one diet versus another. You know, the macronutrient composition is always called into question by people, you know, considering whether this was really a low-carb diet or whether this was really a keto diet or what the different types of fats uh were that were used in a particular study. Whereas with fasting mimicking, there's a clear uh like product that's used which has a certain number of calories and you can't really mess around with it. And I think that's how you can standardize a number of different uh um investigations and use it in a whole bunch of different medical arenas, which to your point is what we want as physicians. We want that standardization in the same way we need that with medications. Um just for the like less than 1% of people that would be willing to undergo uh water-only fasting, which I guess is perhaps the most extreme form of uh calorie restriction or uh um fasting. Um are there any added benefits to water-only fasting uh versus uh fasting mimicking or is are there two just completely un-unequivocal to to compare?

Professor Valter Longo: Well, I mean, first of all, you know, people of course have been doing water-only fasting for thousands of years, mostly mostly because they had to, right? So they were there was no food. Uh and of course, if you're 12,000 years ago, uh and you're having to go water-only fasting, that's okay, you know, you're probably going to have a life of of 55, if you're lucky. Uh and that's okay. Um now, I would discourage, we we I made the mistake of telling people to allow also water-only fasting in my first book, Italian book, and it turned out to be a disaster. Why was it a disaster? Because you now you have to think about what what happens when millions of people do this, right? So, uh and my book was sold very well in Italy, uh and and lots of people, it was almost like a, you know, national phenomenon. So now, we got to see what happens when uh lots of people do something that they're not supposed to do, which was water-only fasting. And you started seeing people showing up at the emergency room, you started seeing people uh you know, having lots of problems, which we didn't see with the more much more regulated, both in the content, but also medically, dietitian regulated. So, the fasting mimicking diet, the box, um always comes with either a doctor or a dietitian. So, there were two layers of problems, you know. One of them, improvisation, it could have been water-only, it could have been some crazy juice or whatever it was. Uh and two was like, I'm going to do it on my own. Uh I'm not going to talk to a doctor, why should I talk to a doctor? I'm not going to talk to a dietitian, why should I do that? Yeah, so that that was a disaster. And so, we basically say, um you know, then I realised why fasting every 50 years came around and disappeared, right? So, every, if you look at history, every 50 years or so, there is a explosion of fasting and then people die and it used to be water-only fasting. So, some patient die and for example, one lady with multiple sclerosis in Italy, she ended up dead after the doctor uh said, do, I think it was three weeks of water-only fasting at home uh to treat multiple sclerosis and she ended up ended up bleeding to death. Uh so, yeah, so then that's just a, you know, one example, uh had we pushed, by then, luckily, we already had said, stop doing any type of improvised fasting, um and uh and so nobody um you know, attacked us for it. But uh yeah, so that that's the problem with with water-only fasting. That's the problem with improvisation. Uh eventually people get hurt and then the medical community rightly so turns against it and say, this is completely uncontrolled. On one on one side, we have FDA, we have a thousand people, uh random randomized clinical trials, um we have, you know, safety data on tens of thousands of patients. And on the other side, you have somebody going home and cooking it up and trying to, you know, with no medical supervision, uh and FDA, you have a prescription, you have from the doctor, etc, etc. And then on the other side, you have complete improvisation. Uh yeah, you see how it has to end up in in in a with a bad result uh and eventually um disappearing. And that's exactly what happened. So, yeah, now the fasting making diet, people always say, oh, but you know, Longo uh is doing it because he has a company with the sales kids. Um you know, and first of all, I I don't take a penny from the company and all the shares are going to go to charity. Uh but you know, I I didn't want to sort of compromise the method that I thought was going to be the right one because people were going to attack me um on, you know, I have a company or not. So, yeah, so it was important and I know I stick with it and you know, and and uh but then again, as you know, half of my book is about things that you can do for free. And I also say, look, if you do lots of things for free, if you follow the first half of the longevity diet of the book, uh and by the way, that also everything goes to charity. Uh and um you know, so if you follow the first half, you're going to need a lot less of of the product, right? Uh and you may not need it at all. I mean, you know, maybe a couple of times a year, but I would say, you know, when we looked at the clinical trial, people that were very, very healthy uh at the beginning, benefited a lot less from the from the fasting making diet than people that that started and being not so healthy, right? So then, yeah, so then there's a free option, which is the everyday option, uh which will minimize the need for somebody to having to do the the fasting making diet. But because most people uh don't want to follow the free option, uh then I think, you know, the the the the prolonged FMD is uh for healthy people is a good way to go. And you know, and I'm assuming we're going to talk about also the uses in cancer, autoimmune diseases, now we're, you know, we're starting trials on Alzheimer, uh inflammatory bowel disease, etc, etc.

Dr Rupy: Absolutely. Yeah. I mean, I think for those two buckets of people, you have those that will definitely take the advice in the first half, which is general advice, very completely evidence-based, and will lower things like blood pressure, that is one of the biggest killers across the world. And then you the other bit is productizing the uh the FMD, the fasting mimicking uh protocol, which, you know, will help those who actually need something to stick to. And it applies to different people's motivations. I wanted to, before we start going into the different trials and the uses of FMD, I want to talk a little bit about the mechanisms because I think there's lots of scant information in the general media about how fasting is good for inflammation or fasting is good for autophagy. But I think it would be good to sort of get an understanding of just the complex pleiotropic ways in which fasting mimicking diets and and alternate uh uh fasting can actually have these effects on the body overall.

Professor Valter Longo: Yes, yes. So, there is a there are a number of um factors. Lots of them we still don't understand. But but I would say the the major effect seems to be A, pushing the body uh towards uh to the depletion of glycogen. So the the the glucose, the sugar reserves are gone. And then forcing the body to start taking from the belly fat, right? So abdominal fat. And uh and that's this ketogenic, this this switch into a ketogenic mode, uh into a fat burning mode seems to be um one of the the important factors. A, uh because um it burns fat and not muscle. So in the clinical trial, we see that uh basically the patients, the the muscle mass, the lean body mass becomes a little bit uh reduced during the FMD and then re-expands after. Now, we we don't have all the details, but certainly by DEXA, by by X-ray analysis, uh we can show that. And um and so that's very good news because now you're burning fat uh and and particularly abdominal fat, but you're not burning muscle, which is really uh not present in in all the chronic interventions. Usually, you're going to lower, including calorie restriction, right? You're going to lower your lean body mass and then uh you're going to lose uh fat also. Uh so, so that is a basic switch. Now, the brain also eventually after day two, three, four, switches to this ketone body uh mode where maybe half of the energy is is no longer coming from glucose, is coming from from ketone bodies and the heart is also now utilizing fatty acids. So it's really a revolution of of metabolism, right? And and and these new uh requirements seem to be very important uh for uh potentially activating stem cells. We've shown this in a number of of models, but also uh getting rid of of cells that are not used to this fatty acid ketone body dependent metabolism. So, yeah, so then this this cleanup reset seems to be probably the the major mode of of uh efficacy. So, as I mentioned earlier, if you have a pre-cancerous cell, by let's say that a cancer a cell now acquires a mutation in RAS, right? And and I won't be too technical, but just, you know, it gets mutated in a in a gene. Um now that cell becomes a a semi-rebel, right? So it starts rebelling. It's not quite fully cancer cell, but it's a semi-rebel. And um so so now when you're starving a system, the all cells in the human body in a very coordinated way. And why is it coordinated? Because it's 3 billion years old, right? So it comes from the the prokaryotes that were fasting 3 billion years ago. Uh and uh and and so, you know, and of course, we we've maintained this response. So, every cell in the in the planet understands starvation, including the one in the human body. Now, the cancer the cancer cell now it became a a semi-rebel and it starts refusing to understand that I have to respond to fasting. So, it cannot do that and survive, right? So, it can it can try to do that, but um it's most likely going to die. Why? If for example, it uses a lot of the lots of cancer cells enter something called the Warburg effect. It it burn lots of sugar. And so now, if that sugar used to be 110 or 130, 140 during the day, uh the cancer cell is very happy. Warburg effect, you know, it uses that moment to expand rapidly and then, you know, it can survive. If it goes down to 60 or 55, um it's going to struggle and eventually it's going to die, right? So, yeah, so then the the the fasting and particularly the fasting mimicking diet seem to be, well, the role of the fasting mimicking diet is to make sure that, you know, the fasting glucose doesn't go past 60, right? And the blood pressure doesn't go past, let's say, you know, 90 or so systolic blood pressure. Um and so that's very important. The the FMD has the job of of uh um you know, protecting the patient from going to a too much of an extreme response uh compared to the water-only fasting. The other thing that was interesting, and so what I just said about the cancer is also true for, let's say, autoimmune cells. So, we've seen clearly in the mouse and we're starting to see evidence of this in in human trials, uh that that autoimmune cell seem, so for example, last year we published that in people that had high CRP, uh we also see lymphocytosis, so increased level of white blood cell. And and only in those people that have high CRP, we see the cycles of the FMD bringing back the white blood cells to the normal level, right? So, you're eliminating this inflammatory increase, inflammation associated increase in white blood cells. Uh so, so it's looking and if you look at uh let's say muscle cells and fat cells that are insulin resistant, we are showing very clear evidence in mice, you know, where we can reverse type one, I mean, both type one and type two diabetes uh symptoms. Um but it also see lots of evidence for that in humans where the insulin resistant cell now is becoming much more insulin sensitive uh during after cycles of the FMD, right? So, so in general, it seems like it's bringing the body back to its optimal function, uh is more youthful function, you know. So, most people don't have cancer, don't have diabetes, don't have autoimmune diseases when they're 18 years old. Um and so, uh that uh sort of ideal balance of cells and ideal function of cells uh seems to be what the the FMD is working towards. And then one thing um that we saw in the mice at least, was that when we compared water-only fasting in the IBD model, so these are intestinal inflammatory autoimmune diseases, um so the if we only use water-only fasting, we actually saw that the gut leakage increased, right? Temporarily, but only temporarily, you see the gut becoming more permeable. And uh and it's not surprising because water-only fasting would be associated with no food in the gut. So, it's okay to use that moment to make uh the um the gut much less dense of cells of villi and then, you know, during the refeeding, become denser. Uh but in the fasting making diet, we didn't see that. Probably because of two reasons. One, uh there's still food in the gut. And and two, uh the the food seems to be giving uh fuel to the lactobacillus and other microbiota and other microbes that are protective. So, now we saw a big expansion in the in the protective bifidobacteria, lactobacillus, etc. Um and so we suspect it is the the prebiotics uh that are contained in the vegetables that are fueling this expansion, which we didn't see with the water-only fasting. So, so very interesting, right? So now, and I think that my idea to combine the the nutrition of the long-lived people of the world with fasting was the right one because uh I didn't know all the mechanisms why Okinawans or or certain Southern Italians live so long, but they certainly ate a lot of these vegetables. And so I thought, I'm not just going to make a a fasting mimicking diet with any components. I could have done with lots of components. I'm going to make it vegan, I'm going to make it using lots of these ingredients that are very common for all these longevity areas. And so, so something they may be benefiting from could be this microbiota, this, you know, uh the vegetables are now making them have a very healthy uh microbe population in the gut.

Dr Rupy: So, just to, I mean, that that was a fabulous description of all the different potential mechanisms. So, just to put it into context for the listener, you have these different mechanisms of fasting. We're specifically double-clicking on fasting mimicking diets. And the number of different effects can be anti-inflammatory, uh reduction in uh glycogen stores, so you increase something called ketones, which is an alternative fuel source. Those ketones themselves can have uh impacts on the brain function, um as well as changing gene expression as well. Um and you have uh the this impact on um uh glucose maintenance as well in the body, which have again impacts on metabolism. Um within all those mechanisms, one that I think is quite interesting is autophagy, which you described, which is essentially this cell cleanup of of cells that are are mutated or pre-cancerous or um damaged in the case of autoimmune conditions. And the body essentially clearing those away and allowing the uh production of healthy um uh cells from the uh the stem cells themselves that that we have uh generally in circulation.

Professor Valter Longo: Yeah, so autophagy uh is probably part of it. Um and um it doesn't seem to be happening as much as people think uh in the early days, you know. We uh we think the most of it happens by day four, five, six, seven. Uh so, uh the body uh before the cells before having major changes in major activation of uh of this self-eating processes, uh probably have to be in a fairly advanced state. But yes, autophagy is something we're studying right now, is uh is certainly uh there and it can be activated and uh and it's part of this general, this universal program of shrinking and self-eating. Uh so, yeah, so shrink uh not just within the cell, but also at the cell number level, um and um and stand by, have the stem cells ready to go, and then when the refeeding occurs, uh be ready to rebuild uh the uh the uh building essentially that uh was taken down during the the starvation period.

Dr Rupy: And so there are a number of different uses uh of of your method of fasting. And I think um perhaps the one that really caught my attention was cancer. Uh we we talked about this a little bit more because I think you must have had some pushback suggesting to patients who are undergoing treatment to reduce calorie consumption during or post-treatment, um because the prevailing belief is that we need to increase calories or maintain weight during uh different cycles of chemotherapy. Talk talk me through how that came about and what the kind of pushback was and where we are at the moment with the clinical trials.

Professor Valter Longo: Yeah, so the the pushback was uh uh major at the beginning. Um you know, and as you said, everybody was under this sort of like old style idea, uh that was not really science-based, it was more of, of course, you got to eat more because I see that you're losing weight and um and of course, you're losing weight because A, the cancer is growing and B, the chemotherapy or whatever is is having damaging effects, right? So, if you reduce cancer growth and you reduce the side effects of the chemo, now you could actually um gain weight by eating less, right? So, um very counterintuitively. So, yeah, so there was a lot of pushback and uh and our idea was like, okay, this is normal, let's just uh face it by doing clinical trials. Let's face it by publishing papers in in mouse studies. And that's what we did. And then slowly, you know, um it went away. Uh meaning, it doesn't, well, I shouldn't say it went away, but certainly now we're in a different, completely different planet compared to where we were 12 years ago when we first published on this. Uh so now you see some of the big biggest hospitals in the world, biggest universities of the world, uh asking us, can we start a trial uh on on whatever use of the FMD and and cancer, going from immunotherapy, hormone therapy, chemotherapy, kinase inhibitors, etc, etc. So, my guess, this year is going to be three clinical papers published. Uh some of them um are, you know, pretty good group of of patients. It's going to be one uh published in the next two or three months uh from a Dutch uh multi-center uh group, um you know, on breast cancer. So you'll have to wait and see. Um there's going to be another one from Milan, another one from Genoa. Um yeah, so this year, uh overall, you're going to see maybe seven or eight clinical trials published on the FMD and different type of uh diseases and also disease prevention.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, that's brilliant. I mean, I'm assuming you're clearly familiar with Roy Taylor's work up in Newcastle with uh very low-calorie diets. How do you feel that they might compare in terms of the efficacy? I know which one I would prefer to do if I was a a type two diabetic patient. Uh it would definitely do the one that's least uh the path of least resistance, which is yours. But the data and the the results from the second year of the direct trial were were quite encouraging.

Professor Valter Longo: Yeah, um I think that um whenever you have something like calorie restriction, because that's essentially I think what they're doing, right? They're doing severe calorie restriction continuously. Well, there are some issues with calorie restriction. One of them is of course compliance. Uh and long-run compliance, right? So eventually, are people going to be able to do it? And you'll argue if they could do it, they would have already done it uh before becoming diabetic. Um and um and the other one is some of the metabolic switches. So for example, we know now from from the work by Ravussin and other that um the metabolism slows during chronic calorie restriction past the weight loss, right? So you lose weight and your metabolism slows even more than your weight loss. So now it sets you up for probably an epigenetic lock in which you're it puts you in trouble, right? Why are you in trouble? Because now you're you're A is a very difficult uh diet and B, now your metabolism is so slow that you're struggling to even eat less, right? So you have, you know, you have to reduce it even more. And um and for most people, that would be very difficult uh long term. Um and so and and the um some of the data that I've seen for epigenetic changes or these changes in metabolism, it could last for years, right? So now you could do something for several months and if you enter a different mode, a thrifty mode, if you will, where your metabolism, your body is saying, we're in trouble here, food is coming in very scarce, I'm going to slow down as much as possible. Uh so now they could put you in a in a trouble situation. So this is why if you look at some of these papers following the American uh TV show, The Biggest Loser, you know, they published, I think it was a JAMA or New England uh paper, uh most of them eventually, this was a continuous severe calorie restriction for together with severe exercise regimen. And most of them had eventually regained all the weight and some of them regained more than the original weight, right? So that's a concern with um you know, both mechanistically and compliance-wise with I'm going to get you there. I could show you I'm going to reverse diabetes or whatever. Uh you know, by revolutionizing your diet and making you eat almost nothing. Um yeah, so we we are of the opinion is, don't do that. Minimize the changes to the diet. Uh you know, use the fasting, the vegan fasting mimicking diet to educate the brain to this new world, right? So because that's what we see, you know, by the time patients do two or three cycles of the FMD, the brain probably starts understanding how much better they feel after five days on this vegan diet. And so that brings most of the patients towards more vegan-based uh ingredients. And also, it it it seems to be doing the opposite of this long-term severe restriction, which is that the metabolism, at least in mice, we've shown it, uh they eat the same and they burn lots of fat, right? So it's probably uh keeping the the body in a, you know, in a catabolic mode uh um longer, at least for fat. And um so, yeah, so I mean, at least for these reasons, uh I I'm more, I mean, but hey, let's see what happens and let's see how feasible some of these uh interventions coming out of Newcastle are in the general population. And um you know, absolutely, um you know, I'm not saying that uh one is better than the other. I'm just uh pointing to the sort of process that we went through in deciding, you know, how do we make it for everyone? How do we make it uh feasible to everyone? And how do we prevent this uh molecular changes that could put the patient in trouble um without the patient really understanding that, yes, I'm doing a lot better, but potentially, like the biggest loser, I'm doing a lot worse. It would have been much better not to be put in this, you know, however many months of, you know, exercise and and which everybody would say, oh, this must be great for you, you know, you exercise a lot and you ate very little. And look at the wonderful results. And um and as you probably know, this yo-yo uh effects eventually shorten your life. So it's better to stay overweight or obese than to go obese, skinny, obese two or three times in your life. Uh now, that's associated with a shorter lifespan. So, so, yeah, so this is the science that needs to go into it rather than uh oh, I'm observing a good result, that must be good, you know. Um yeah, so that that that's the only uh caution that I would uh bring up there.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, absolutely. And I I'm I'm totally in agreement with you in agreement with that, particularly with patients, I find the most effective way to help people change their uh way of living uh and maintain that way of living is making small changes that they can stick to and that's agreeable to their long-term goals. So, one of the most effective things that I've done is tell people to eat in a rough 10 to 11 hour window or 12 hour window to start off with. And I don't even, I say to them, I don't care about what you're eating within that window. Obviously, I do, but to start off with, just just promise me you'll eat in that 12-hour window. And the number of people who then go on to make massive changes months down the line is fantastic to watch.

Professor Valter Longo: I think it's a great method, you know, I think you're absolutely getting it right, you know, just stick, can you do? And I do the same thing. Can you just do 12 hours, you know, and nothing else? And then they're a little bit surprised and say, that's all I got to do? For now, yes. And then, you know, and B, in my third book now for children, I talk about the B is like, can you just reduce your starches by 10% a day, right? And people don't realise, then we do the calculations, if you take the pasta, the rice, the bread, the potatoes, 10% down. So, well, don't I need to get rid of it? Absolutely not. Don't I need to go low carb? Absolutely not. People on low carb diet live shorter. And it's better to be, based on the Lancet meta-analysis, it's better to be on an 80% carb diet than on a low carb diet, right? So, no need to go on a low carb diet, but yes, you need to intervene on those carbs and those starches particularly, the pasta, the bread, etc, by 10%. And 10% every day, it means and use the scale to make sure you're it's you're doing it because if you do 10% for five days and then you you overeat by 50% one day, then it's pointless, right? But I think if you stick with it, um so then, you know, I think in my opinion, the overweight and obesity reversal could take two years. Nothing wrong with it. You don't need to show, you know, that in two months you can cure somebody. You know, get them cured for life, take two years of time, and by the two years, they'll, you know, get them excited. I think with the FMD, we get them excited because the patient sees the effect short term and is excited also about going back to the normal diet. And so that's a that's a good way, right? Because if you see, if somebody puts you on a Mediterranean diet, you don't really see the changes and lots of people are going to abandon it because I don't see anything yet. Uh so, the FMD plus these small changes like you're doing, I think uh are ideal because the patient sees the effect and then they're more motivated to stick with it. And and the changes are so minimal that um they can actually do it long term.

Dr Rupy: Absolutely, yeah. Well, thank you so much for your time, Valter. I'm a massive fan of your work and I'll continue to follow it. Um and thank you for making the time for this.

Professor Valter Longo: Okay. All right. Thank you.

Podcast Intro: I really hope you enjoyed that conversation with Prof. He is an absolute superstar in the world of academia. In fact, Time magazine um labelled him the guru of longevity. And that's for his incredible work that has spanned decades looking at the field of aging or gerontology as it's also known. Um and the work that he's done in uh FMD. And you can tell just from the reams of different trials that he's involved in that he is a pioneer in this uh field. And it's certainly going to change the way we look at uh medicine and nutrition uh as an adjunct to to each other. So, um I hope you enjoyed that. Just to recap, different types of fasting, alternate day fasting, water day water fasting, uh time-restricted feeding, and FMD kind of fits in with alternate day fasting. Um the mechanisms are anti-inflammation, they change the gene expression, they probably upregulate uh certain genes that are protective, in particular the sirtuins. We didn't get to get to talk about that, but he does talk about that in some of his books. Um autophagy, which is this process of cell cleanup, essentially removing cells that are damaged or mutated or just sort of hanging around and not really doing much. Um and the uses are of this um fasting mimicking diet regime can be applied to obesity, um type two diabetes and metabolic syndrome for sure. And there may even be extended uses uh in autoimmune conditions uh and different types of cancers as well. Cancer is an umbrella subject, um and it it can apply to a whole bunch of different disease states. So, again, just to reiterate, this isn't an advert for fasting. We still have very little evidence about the efficacy and we don't know the doses and whether it's appropriate for certain people or not. So, again, just caution with this information that it isn't uh for it's purely for information and it's not for use and there isn't uh an advert or uh a suggestion that everyone should be doing this. Um we talked a little bit about the future as well. Check out his longevity diet. It's a very easy read where in the first part he talks about uh the longevity principles, which pretty much marry up with mine. It's largely plants, lots of colours, plenty of quality fats, as well as fibre, fibre, fibre. And he's, as you can tell from his kind of ideal meal, lentils, pulses, beans is exactly what I tend to do in the kitchen too. Um it's difficult to close this because I think there's going to be a lot more information around the uh fasting sort of topic. And I'm hoping to interview a few more people on this uh subject matter in the near future. So, look out for those podcast episodes. Subscribe, give this a five-star review if you enjoyed it, and I will catch you next week.