Dr Rupy: If you’re skeptical about multivitamins like I am, this is the podcast to listen to because it might just change your mind.

Dr Rupy: Hi, I'm Dr Rupy. I'm a medical doctor and nutritionist. And when I suffered a heart condition years ago, I was able to reverse it with diet and lifestyle. This opened up my eyes to the world of food as medicine to improve our health. On this podcast, I discuss ways in which you can use nutrition and lifestyle to improve your own well-being every day. I speak with expert guests and we lean into the science, but whilst making it as practical and as easy as possible so you can take steps to change your life today. Welcome to The Doctor's Kitchen Podcast.

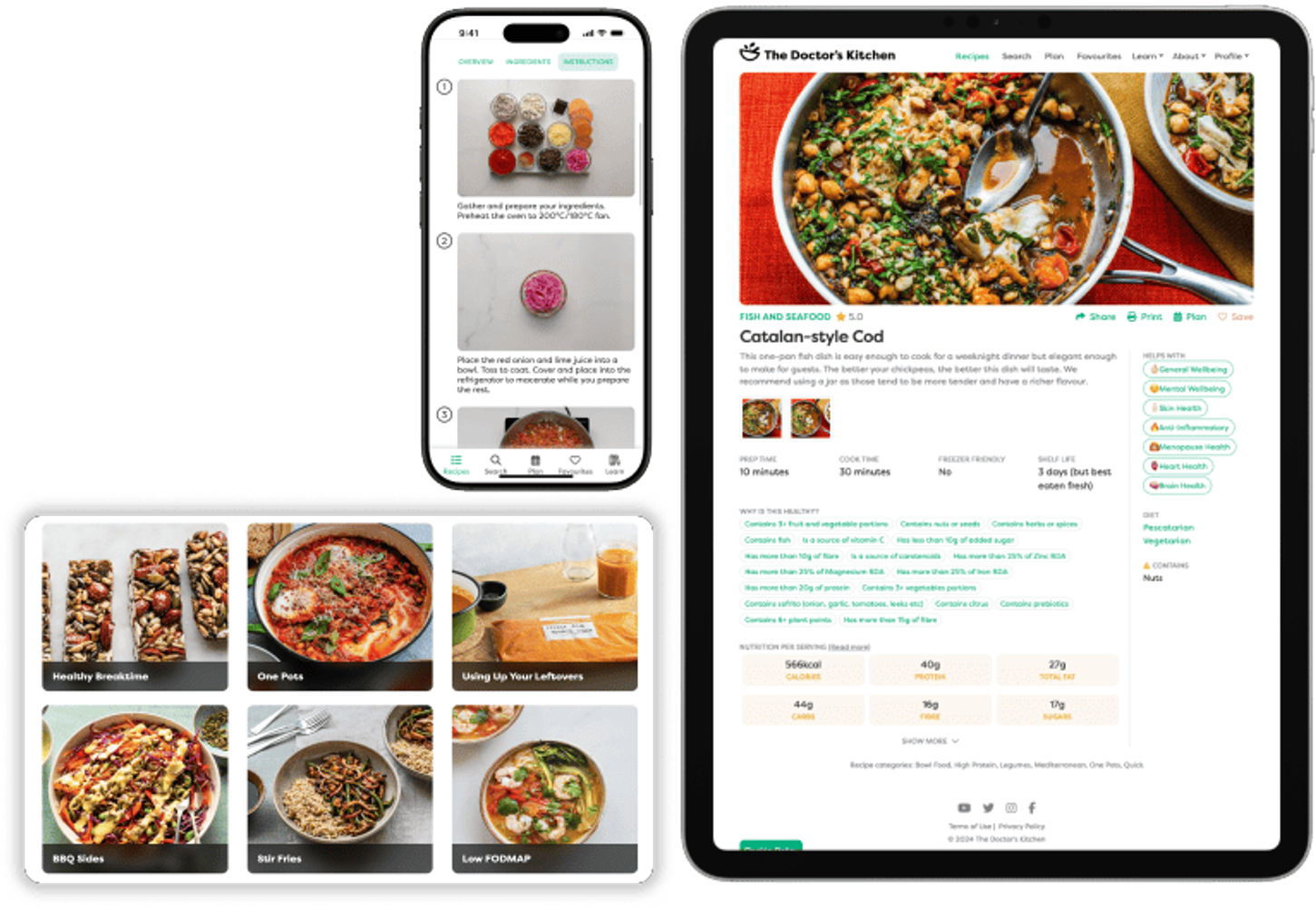

Dr Rupy: Coming into this podcast, my opinion was that multivitamins are just not worth it, whether it's for general wellbeing, cardiovascular health, sleep, and especially mental health, I was just not convinced that they did anything at all. But I specifically wanted to speak with Professor Julia Rucklidge, clinical psychologist and director of the Mental Health and Nutrition Research Lab at the University of Canterbury, because she has a very different opinion. Julia's ground-breaking research and viral Ted talk have transformed how psychiatrists and other mental health practitioners think about nutrition and mental illness, especially the potential of what she calls broad-spectrum micronutrients to support mood, focus, and resilience. So today, we're going to talk about multivitamins specifically in the context of mental health. We're going to talk about why there are no single-ingredient solutions and where multivitamins may actually help. How stress, inflammation, and modern farming have changed our nutrient needs, the mechanisms linking micronutrients and the mitochondria and neurotransmitters to mood and cognition, the evidence for micronutrients in ADHD, PMS, depression, and anxiety, and how to choose quality supplements and avoid the hype if you choose to try them. Now, if you've ever wondered whether taking a daily multivitamin is worth it or how food and nutrients impact the brain, hopefully this episode will challenge your assumptions as it did mine and expand your understanding of nutrition for mental well-being, whether or not you choose to have supplements or not. Julia has honestly made me reconsider my personal perspectives on multivitamins, and I'm excited to dive deeper into this topic on future podcasts and with our internal research team at The Doctor's Kitchen. And I want to shout out our internal research team for the Doctor's Kitchen because they're across everything, whether it's our YouTube videos, our content on podcasts, our articles, our newsletters, and also The Doctor's Kitchen app, which has health goals that we have aligned to dietary patterns and ingredients that have evidence of improving said health goal, whether that's skin health, mental wellbeing, brain health, cardiovascular health. We have painstakingly gone through so many different papers to determine which foods and which recipes would actually align with those goals. And this is something that you can try for free by downloading the Doctor's Kitchen app. You'll get access to over a thousand recipes that will enable you to plan meals, get culinary inspiration, plan them on our meal planner, cook them and track them as well with our handy tracker that enables you to take a snap of your plate, whatever you're eating, and then determine whether it's high in fibre, high in protein, and low in inflammation, something that I encourage everyone to think about regardless of what your specific health goal is. You can try it for free by downloading The Doctor's Kitchen app in the link in the podcast description. And something else you can get for free as well is a free trial of Exhale Coffee. Exhale Coffee is the brand of coffee that I'm the Chief Science Officer for, and I'm so, so into coffee. If you're not already aware, I'm a big advocate for getting good quality staples in your diet. We lab test our coffee to ensure that it's high in polyphenols and it tastes absolutely delicious. And if you don't believe me, try it for free for yourself by clicking the link in your podcast caption description. This is going to be a great episode for anyone that's skeptical of multivitamins, as I was. And, uh, hopefully it sort of nudges you to think about things in a wider perspective, as it has done myself as well. I really hope you enjoy this conversation that I'm having with Professor Julia Rucklidge. To keep our podcast completely free for you, our lovely listener, we're going to hear a quick word from sponsors who make that possible.

Julia: Julia, uh, the US Centers for Disease Control says that there's a 50% lifetime risk of mental health problems. What on earth is going on?

Julia: I find that a really tough question to answer, but I'll do my best. Um, I think that your standard reply on that kind of question would be that we're getting better at diagnosing it and that people are more likely to be coming forward about their mental health challenges. But I really feel like that can't possibly be the full story because it's implying that in the 1980s or the 1970s, uh, that we weren't recognizing that people were struggling and that we would let them be and not talk to them. And I just don't think that's fair to my parents or my grandparents to assume that that's how they were behaving. So I think there's been a lot of environmental changes over the last few decades that could easily explain why we are more distressed than we were. And I, the way I think about it is that I think that we are possibly less resilient than we were, and an easy way to think about resilience and how that that could have reduced over a fairly short period of time is that the food environment has changed so dramatically and drastically over a very short period of time. So, you know, the rise of ultra-processed products in the last 50 years has been unbelievably exponential. And when you break down what has what happens as a consequence of the increased consumption of those foods, which is 50% of our calories are coming from those types of products. I think that's the UK data is around 50-60% of the calories are coming from those types of foods is that there's, I think about them as there's three things wrong with them. One of them that you'll often hear people talk about is the sugar, and that's, yeah, fair enough, there's sugar. Um, another one that you might hear people talk about is the added things into it and that you end up with these cocktails that we are consuming at a really high rate that we're not used to dealing with. And that would be your emulsifiers and your preservatives and your colours and your flavours, all of those things that have been added to it to make it taste good. And we're starting to recognize that that in itself is having an impact on our microbiome, which then impacts your brain. But the third one that I think gets overlooked and not really talked about in the conversation, which is my area of research is the that that it is the micronutrient content. And so the vitamins and minerals contained within ultra-processed foods is way, way lower than what you'd get out of real whole foods. And when you start to break down why what do micronutrients do for the brain, and you realize that they're involved in everything, metabolic reactions, supporting your mitochondria, helping keeping your genes healthy, reducing inflammation, all of those things, when you start to unpack that, and then you're not consuming them from a ultra-processed type of diet, you start to realize that our tanks are empty to begin with. And then you start throwing stressors on there, COVID, in New Zealand it would be like earthquakes and floods and other environmental disasters, people have nothing to start with. And so they, I think they end up being far more stressed than they might have been had they started with a full tank.

Dr Rupy: Yeah. How's that?

Dr Rupy: I mean there's so much to unpack there. Absolutely, yeah. I, I, I really love this concept that you talk about quite a bit in your book, um, The Better Brain, about resilience. And, you know, some of the analogies you've just spoken about there with the tank of fuel, not having a full tank, not having the ability to withstand stresses as much as we perhaps would have done 40, 50, 60 years ago and beyond. I'd love to unpack that a little bit more. So I, I totally get the food equation in that. There's been a drastic change in the way we eat, the timing of when we eat, the impact on our microbiota. What else is picking away at our resilience that has potentially leading to this increase in mental health problems?

Julia: What else might be picking away at the resilience? Um, I think, I mean, I think other ones that are obvious that are outside of the nutritional realm would be your rise in technology, social media. There's, I'm sure you've had experts who can talk to the impact that those things can have on our overall resilience. Um, and that they are in a unusual way reducing, I think, our our our physical social connections that you would get out of um, meeting with people and then if you're just always online, then do you experience social connections in the same way as we would? And we know how important social connections are for longevity, for quality of life, for having those support systems. Has that been eroded at the same time as our nutritional environments? I think we have almost like this collision of disasters coming together to perhaps explain why so many of us are struggling with our daily living. Um, and then, of course, you can look at sedentary lifestyles and we're not moving enough and um, we've we've lost touch with things like um, nature and green spaces and blue spaces and you kind of look at it and you go, wow, we've we we're not building up so many of these skills that perhaps our ancestors might have just naturally built up just as a consequence of their environment. I don't know if that's what you were thinking of.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, I mean if you think of like the inputs for a healthy brain. This is actually something that me and Dr. Drew talked about recently in a podcast who I know you know well. Um, we've taken away all those inputs, movement, exposure to nature, um, and we've added things like ultra-processed food and tech. One other thing that you mentioned in your book is um, polypharmacy or the number of medications that we're now exposed to. And I wonder if we could talk briefly about that in in in relation to how that might be in some way uh, impacting our resilience.

Julia: Yeah. Well, I don't know, I mean that's a that's a good way to think about it because I haven't thought about it in the perspective of resilience, but I I think the way I would frame it is that we've, the 1980s was a really exciting time. I did my first degree in neurobiology. And it was all about understanding neurotransmitters and dopamine and serotonin. And it was also the year, 1987, I think is the right year, where Prozac came on the market. So there was a real excitement around we've found the answer. You know, I go into this field of mental health, I became, I was really interested in becoming a clinical psychologist. And I was excited about the opportunities that we had to maybe really make a big difference on people's lives. And that's, you've got this rise of excitement around the chemical imbalance theory. And that, you know, if you just, if you just give an SSRI, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, it's going to influence the levels of serotonin and then people are going to be fixed. And the same thing with dopamine and just such an exciting time to like have hope that there we're at the we're we're getting to the cure. And the sad thing is is that it didn't turn out as well as we had hoped. And but we ended up not realizing that until probably really recently. And there's now a lot of discussion around was that really the right way to think about mental health issues and it's more complicated than that and it's not just about serotonin and, you know, it's it's about, you know, that's just having a a change, a chemical change. It doesn't cure it, it's not addressing the root cause. So we're starting to have those really, I think important conversations. But when you have a magic pill available, we end up using it and we end up using that as the first go-to and we don't then allow people to perhaps heal in a different way because they think about their mental health problem as being something like having heart disease. It's I have depression, so therefore I have to fix it with this pill in order to correct it, and that will fix it. And so we have generations, a generation of people who think about mental health disorders as being fixable by that pill. And I think that took away their control. And I think it's taken away all of our control of thinking, you know what, there are things that you can do in order to improve your mental health problems. Absolutely. But when we start with the pill, we take that away, I think. And so I think that's maybe what you're maybe think about it differently. But yes, I think it means that then we don't build up our skills to deal with mental health problems.

Dr Rupy: So I like the way you're thinking about it, Rupy.

Dr Rupy: I think the, you know, just thinking back to my experience as an NHS GP for many years, um, the way we thought about medications was very guideline driven. It still is to some extent today. I'm really pleased to see a lot of practitioners across all different specialities thinking about medicine in a completely different way from sort almost like a a resilience mindset. But in the context of a short appointment and consultation and the almost the demand from a patient in some ways to have a problem fixed, especially when you are fed this idea that antidepressants will anti the depression you have. It's no wonder the number of prescriptions for uh, these kind of drugs have soared over recent years. And actually, in your TED talk and in your book, you you talk through some of the data around the increase in prescriptions, not just in the US, but also globally, and in New Zealand, which is absolutely.

Julia: Exactly. So it's like it's like 17% of the adult population, it can go up to 20, 25 depending if you're female or not and depending on what age band you're in. So one in four one in four um, yes, if I I'm not sure exactly what age band it'll be your older female, but yes, you've got a very high percentage of people on them. That doesn't necessarily the mean that those people are well though. That's the sad thing is that when you dig into the data, and that's something that I've had the opportunity of doing with my own data, like just studies that we've done and in fact it's what led me to do what I'm doing now is that I, do you want me to go into it? So that a good question. I mean we're going to go a little bit off topic around your question but maybe if I remember I'll get back to it. So I started, uh, I did my my Master's PhD and my my professional training uh, for becoming a clinical psychologist at the University of Calgary in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. And I did my PhD not on nutrition at all. I did it on women with ADHD, so completely different topic. And um, but when I was doing my PhD, I uh, with with Professor Bonnie Kaplan who I co-wrote the Better Brain with, she she heard about some families who were in Southern Alberta, Canada, just about two hours south of Calgary who had discovered this idea that you can if you give people additional vitamins and minerals, you can make a huge substantial change to their mental health status and particularly what they were looking at was bipolar disorder psychosis, so really serious, complicated mental health challenges that my training in clinical psychology had taught me, uh, was could only be treated with medications and psychotherapy and that nutrition was irrelevant to the brain. I mean that's the standard training that a clinical psychologist gets, the standard training that a psychiatrist or even medical professional gets is that as long as you eat a healthy diet, whatever that thing is, I mean we can unpack that. But um, then you're you're you don't need to worry about that aspect and it's not relevant and it's not important to think about it that way. But these people were getting well and staying well with nutrients. And there's a a long story about why they ended up giving that a go because they had long histories in their families of people who had mental health challenges and conventional treatments weren't helping. And or helping those families. And so they decided to explore an idea, which is that when animals get very irritable, sort of your your your what might look like a kind of a a manic or depressive type of state in an animal. I know it's a kind of a bit of a stretch. But uh, that you give them a broad spectrum of micronutrients and then they calm down. And that's what you do when you're a farmer.

Dr Rupy: And this has been known in agriculture for years?

Julia: It's been very well known in agricultural spheres. Yeah, they don't give them anti-depressants, they give them nutrition. So they applied that concept to these families and to these children who were really struggling. And they came up, they realized that they were getting well. So rather than start a company that could, they're just go and sell their product, which you can do as a that's as a vitamin and mineral. go ahead and just sell it when we I'm happy to talk about that because there's a lot of crap out there. Um, that they wanted scientists to study it. And so one of the scientists that they approached was Bonnie Kaplan. And so I heard about her getting, she was skeptical, she thought it was snake oil. But she saw their data and one of the things that I learned from her and that I try to instill in my students is that if an idea completely contravenes your way of thinking, don't shut the door on it. Be curious. Be skeptical, that's fine. But be curious about it. And that curiosity could lead you who knows where. And that's what's led me to be here sitting and chatting with you about it, is that curiosity. So I um, I ended up finishing my PhD. I went and did a postdoc at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. And then this opportunity came along for me to move to New Zealand because they were looking for a child clinical psychologist to teach into the clinical psychology program at the University of Canterbury. So my husband and I were in our, you know, early 30s and thought, why not New Zealand, they speak English, let's go there. So we moved there, we agreed we'd go for a couple of years and we're still there 25 years later. But I am going to get back to your question. And that is that I continued to do the work that I was involved in, which was in looking at gender differences in ADHD. And one of the things that I noticed in our data was that we were recruiting people with ADHD who were medicated. So they're taking the best of the best stimulant medication. And when you look at their scores on the measures of ADHD, they are still in the clinical range. And so they're still elevated. you know, on average. Of course, there's some who will be within the normal range as a consequence of that. But on average, they're still in the clinical range.

Dr Rupy: So these are folks who are on meds who are still having the symptoms of ADHD specifically.

Julia: Exactly, looking at ADHD symptoms. And so you need to that should make us all stop and go, well then it's not working if it's not in if you're not in remission, full remission, then that medication isn't working the way it should. Because I'd think if you're depressed on antidepressants, you shouldn't be depressed. So going back to those stats of, you know, one in four, one in five, a lot of those people are still depressed. And we looked at this within the context of a study we were doing on looking at the genetics of of um, adverse effects and and antidepressants. So we recruited people who are on antidepressants, but we were interested in side effects. But we also looked at their scores on depression and a lot of them were still depressed. So I think we owe it to people who are struggling with mental health issues to be honest about these data, to recognize that not everyone gets well. And I do always like I always think it's important to say is that there are people who do really well with these medications. I tend not to see them. So they're they're out there. Um, and they tend not to come to me or to, they don't come to a clinical psychologist and they don't um, tend to come to our studies because they're doing really well and they save lives. But we also have to be honest that not enough people are getting well, because if people if they were working the way they should, which is to put you into remission, we should not have that stat you told me at the beginning, which is half the half of people um are going to have a mental health challenge. We shouldn't expect that if these medications are working the way they should. You should eventually see a drop in the number of people who are struggling because they take the pill and they get they get better. But what happens now is they take the pill and they don't always get better and then they can't get off of them because of these challenges of the withdrawal. And I you know, I certainly have personal experience of, you know, I have a my mother who's who's passed away now, but she um, struggled with anxiety in the 60s and when that happens, you were put on a medication. And and she could never come off of it. I eventually we managed to get her off of that with a lot of support with nutrition and things like that. But that withdrawal is can be absolutely hideous of coming off of these medications that people will put you on with absolutely their best intentions there of making you feel better. So I don't want to um, be negative about the the use of them, but one of the side effects is that it can be really hard then to develop other coping styles. So did I get around to, I think I did eventually get there to answer your question, but I gave you a bit of my story as well about why I'm here.

Dr Rupy: So I want to dive into that actually a bit more about your background. But just before we do, I want to play devil's advocate. Imagine there was someone who was representing pharma sat opposite you right now. And I and my argument to you would be, well, whilst the data shows that people are still having symptoms, it speaks to how multifactorial mental health illness is. And actually we're optimizing as much as we can with medications, but it's the other things, the lack of movement, the technology, the food, the all the other things that are chipping away at people's resilience. And had we not been giving these folks the medications, they would be a lot worse.

Julia: I and that's an interesting perspective. I disagree. I disagree from having seen so many people who have embraced the the um lifestyle factors and really addressed them whether or not it's changing their diet or it's getting them to move or it's getting them to, you know, meditate or all of these other opportunities that we have at our doorstep. I would say that I've seen far too many people do well and also not just do well, but flourish. And I'm not convinced that with just the medication, people tend to flourish with that approach. And there will be some who do. Again, I don't want to minimize that, but I just don't I have seen enough people in my in my career to know that and to know that they they often just kind of get by and maybe they can go to work, but they're not happy. Like are they do they get to that kind of sense of purpose and meaning and and feel energized and excited? I'm not convinced that happens and it's and it's not just from the people who I've met, but it's the stories I've I the emails I've received for the last two decades and it's, my father, my mother, my brother, my daughter has been on these medications and and they're still unwell. I mean that's the kind of conversation starter that I get. And so enough of those you kind of have to think, I don't know.

Dr Rupy: Yeah. Um, I want to go back How was I on the devil's advocate.

Dr Rupy: No, no, no, absolutely. I mean I completely agree. you know, it's just I, I know the pushback that people will give to the idea that we shouldn't be prescribing as much in terms of mental health medication, psychiatric meds. Um, given it's such a complicated topic. I think it's always important to just draw out the nuance, even though I'm in complete alignment with you about the importance of movement and uh, tech addiction, food, mindset, there's so many other inputs that we should be exploring before we even have the pharmaceutical conversation because of the some of the issues that we'll go into a bit later with withdrawal symptoms and the side effects and the how that affects nutrients in general, how that affects you about yourself, your affect. I mean as in like your your general sense of of well-being and mood and you're able to your ability to interact with folks. I mean this is all something that needs to be um put into consideration. But in the context of an eight-minute consultation when you are recognizing someone who's depressed and you want to give them a quick fix, it's like we'll start you on.

Julia: I'm sympathetic to that the system is broken. Yeah. I'm absolutely sympathetic to that. And and I'm also aware of studies that were done with children with ADHD where they um, if they gave them the behavioral interventions first before medication, they were far more likely to engage in that. But if you gave the medications first, they were less likely to engage in behavioral interventions. So we know that if you put the medication in first, then you may be less likely to engage in all of those other things. So I like to think about the medication is the supplement and that you're yes, it might have a role. Yes, it's a what a great um, discovery and development and invention, uh, all of these medications are. But we put them first and I would say let's let's not necessarily give them out first. Let's see what else we can do. I mean, I've done enough clinical trials now, you know, the gold standard that people like to talk about randomized control trials where you randomize people to a placebo pill or in our case we give them micronutrients, but others might you might have a an antidepressant or whatever. I've done enough of those trials to know that the placebo effect is huge. And that just that care um, of looking after someone, being interested, asking questions, and giving them something to swallow is sufficient for in some of our studies up to half of them get better that way.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, that's crazy.

Julia: I know it's crazy. Exactly. And our placebo effect in New Zealand is getting bigger and bigger to the point where I think someone else has to do my research because they come into my office. I know they're already better.

Dr Rupy: It’s your personal placebo effect at that point.

Julia: I think our placebo effect is going up. And I think that that happens with um, medications as well. I think the placebo effect goes up because you have such high expectations and that that in itself is um, it's it's like you're giving people permission to heal. We we've just done a study with teenagers. I cannot believe I did a study with teenagers when I look back on it I go, what the hell was I thinking, 12 to 17-year-olds. And um, and it was and those those data aren't aren't published yet. So I won't I won't talk about what we found, but I'll talk about the experience. And that is that we um, found that these teenagers were because we were giving them a pill, it was almost like we were giving them permission to behave or something that it wasn't that their parents were telling them that they had to, you know, be less grumpy or irritable or have temper tantrums or whatever. There was something about that pill that that allowed them the permission to heal. I'm not sure, but it was absolutely fascinating because we did have a we had a big placebo effect with those teenagers and it was we were targeting teenagers with serious emotional dysregulation. They were really irritable, they were aggressive, they were your teens that most people would not want to deal with and we said, bring it on. Those are the kids we want. And and yet, when we've looked at the data, we've we've certainly observed again that with teenagers, give them a pill, permission to heal.

Dr Rupy: And what's the scoop on that? Like I know it's not published yet, but uh, what was the and what was the intervention? Was it micronutrient?

Julia: The intervention was micronutrients and targeting emotional dysregulation. We've we've come to the conclusion that that is the biggest effect of the micronutrients is on dysregulation of emotions, which which is a trans-diagnostic concept and it transcends against across anxiety, depression, ADHD, ASD, it's at the core feature of so many of our challenges. But that's the kind of kids we were trying to capture. So they had they didn't have to come in with a diagnosis, what we wanted was that they were disregulated.

Dr Rupy: Gotcha, gotcha. Let's talk a little bit about your background actually because you mentioned you did your first degree in neurobiology in the 80s and that you've been doing research, but what what was going on in your timeline in between then? And perhaps we should unpack exactly what a clinical psychologist is for the listener as well.

Julia: Okay, sure. So my timeline, grew up in Toronto, which is explains the accent. And uh, went to McGill to do the degree, my first degree in neurobiology. It was the it was one of these kind of when you look back on it a kind of a dumb decision as an 18-year-old that I wanted to study psychology, but psychology was an art at McGill and I had a scholarship to study science and so neurobiology was the closest I could get to being able to do a bunch of psychology courses and yet um be able to keep this very small scholarship. At the time it must have felt like a lot of money. Yeah. So that's what led me to do neurobiology. And then I took a year off and I traveled and then I came back and I did my master's and PhD in clinical psychology. And so and that's a a standard way through to practice as a clinical psychologist in Canada and the US.

Dr Rupy: Gotcha. And so you don't prescribe meds?

Julia: No.

Dr Rupy: But you are part of the multidisciplinary team that would be looking after individuals with.

Julia: Exactly. So clinical psychologists are the way I think about them now and it's not how I would have thought about it at the time, but I see them as the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff. And so that we wait until people are unwell. I mean I now think about it because I think about resilience. And so I think we can prevent mental health disorders in lots of people if they were more resilient. I think we would stop them from needing a clinical psychologist. And so I now um, focus far more on prevention and I love to talk about that and what I'm doing in that space and improving resilience in university students. So, um, I I but a clinical psychologist would take people who are struggling with your, you know, serious anxiety or mood disorders or ADHD if it's children at the time at least, that's more now a cross the the lifespan kind of challenges and help people through uh, talk therapy to help them get better. And I think there's a lot of value there. There's a lot of value in talking to people and giving them other ways to think about their problems and challenging their thinking and a lot of clinical psychologists are trained with a cognitive behavior model, which is where you're looking at activation and also um looking at thought processes and the way they think about problems and getting them and and their thoughts and getting them to challenge them and see them in different ways and the hope that that conversation and that changing the way they're thinking about it and their thinking patterns can alleviate distress. And we know that that can be incredibly effective. But now that I now I think about it is that we're waiting people we're waiting for people to get unwell and then they get to see a clinical psychologist. You don't see a clinical psychologist as a preventative tool. Although some clinical psychologists probably do go more into that kind of space but and it's so broken. It's just it's like saying let's let's wait for you to get your heart attack and then we're going to do something about it. I mean you guys would as medical people should think that's absurd. But that's what we do in psychology is that we wait until people are unwell and then we we give them skills and tools. Well, why didn't we do that in school? Why didn't we give those those skills to people when they go to university because university students, huge mental health challenges. Goodness, it's that's escalating and going up. So that's where I think we need to target our our resources is to help people stop getting to the the bottom of the cliff and then and then sending the ambulance there.

Dr Rupy: If you think back to when you were a freshly minted as a clinical psychologist, what were your thoughts on multivitamins and micronutrients at that point?

Julia: Oh I would have thought they were completely a waste of of time, yes, a waste of your money. As I said, my training was your standard conventional training which was that nutrition was irrelevant to the brain. And so if you were to tell me at that point, vitamins and minerals would help alleviate distress, I would have ignored it. Yeah. I would have probably ignored it. In fact, I remember um, when I would go and talk to families about ADHD because that was part of my research. And there were some families where they would tell me about diet and and, taking out the colours and the, the, some of the the numbers, you know, making sure that their kids didn't have exposure to them. And I just thought, what the hell? Like why are they doing this and and now I realize they were really um ahead of their time, these these mothers who were looking at the food their children were eating to see whether or not that might be contributing to their behavior. And we now know how relevant that is to the expression of ADHD for example. We know it's not everything and it never is. I mean it's not everything and I don't I certainly don't want to give that impression that this is a cure for for everything but it's such a big elephant in the room that we haven't been talking about that I think there's so much opportunity and it's such a low hanging fruit opportunity because it should be relatively easy to change. So yeah, I definitely was not embracing it at the time. But as I said earlier, you when Bonnie started to look into this and she showed me the data, her early data, um, I was certainly intrigued and I was like, well, I guess we aren't doing that well with our current conventional treatments, why not give this a go? Why not do some clinical trials? Because either I had nothing to lose, right? I either show it doesn't work and then you'd think people would be really excited by that or interested and and go, okay, it doesn't work. But if I showed it worked, you'd think the world would embrace it. Well, they haven't but you would think that there would be great excitement about this opportunity of using nutrition to um, reduce or even eliminate mental health challenges. Or even prevent. you'd think that this would be big news, but it hasn't been big news which is really been a peculiar journey but um, just how much opposition there has been to this idea.

Dr Rupy: Well let let's talk about this because you've had, you know, by sounds of things, uh, a decade plus of having to change your mind very gradually in the face of new data. And I want to give people a snapshot of that in the next hour or so. And I also want to give it to myself as well because as, you know, conventionally trained medical doctor, practicing for 15 years, masters in nutrition, my perspective on multivitamins is still such that I think they're useful for a very small slither of folks who perhaps are malabsorbing and don't have a very good diet, so it might be a good insurance for them. But actually, we should just be getting people to eat healthy as much as possible and in the realm of cancer prevention, cardiovascular prevention, even mental health issues, my perspective is I don't really know of the data to suggest that they're useful, looking at large cohorts. Yeah. So we've been dancing around this. So let let's dive into that. I want you to I want you to convince me.

Julia: And I'm happy to. And I do want to preface this with a few things that I think are important for your listeners. One of them is that as a my research is proof of principle. which is that our nutritional environment is not adequately meeting our brain's needs at the moment. So that we currently have a mismatch between what our brain needs and what we're consuming. So the diet studies are very hard to do. People know when they've been randomized to broccoli, right? Yeah. or McDonald's or whatever it is. So diet studies are incredibly hard to do and people will tear them apart because they can't be blinded. So I see my research as sitting within that that realm of being able to do placebo controlled trials, the gold standard pharma-like trial and my trials are done exactly like that, like a pharmaceutical company would. That we um, are proving through our research, when we show that the nutrients outperform placebo and we maintain the blind and we we put some riboflavin into the placebo so that that changes the colour of the urine so no one can guess on what condition they're in. There's not a lot of side effects so you can't guess based on side effects that when we show that the nutrients are better than placebo, that actually is saying that there's something wrong with our food environment that you're not getting adequate vitamins and minerals from your food. So I first want to say that. The other thing I want to say is that as a consequence of my research, I'm not here to supplement the world. I'm here actually to say we need to change the food environment. So I'm completely on board with you in that food should be first. But I also know that there are people who have incredible diets, really good, incredible, but really decent diets, the ones that you might recommend who still benefit from the vitamins and minerals. And we've never been able to show that diet um quality is um is impacting response. So people of poor diet quality and good diet quality still seem to benefit from this intervention, which is a curiosity, I know. It's a curiosity.

Dr Rupy: It's very interesting.

Julia: And so that deficiency thing I'm going to challenge you on and that you have to be deficient to benefit from additional supplements because I really do want to talk about that. And the third thing I want to say, so food first, um, I think it's proof of principle, but the third one is that I am not paid by anybody to do this research. And so I think that's important too. So the companies that make the products um, are have never supported it financially. They give the product, the nutrients and the placebo for free for us to run clinical trials, but they never tell us what to do and they don't learn about the results until I present them at a conference or publish.

Dr Rupy: Okay, right. So just to make that really clear.

Dr Rupy: That's great. No I'm I'm really glad we went through this caveat. And amazing that uh the attention to detail about putting riboflavin in the placebo so the P changes colour.

Julia: Yes, yeah.

Dr Rupy: It's no wonder the placebo effect is so high.

Julia: Well exactly, but we also put vanilla sachets in all of the, in the bottles and we give them this um sort of a container because they do have to take a lot of pills. They take they're taking up to 12 pills a day so that's four three times a day. So we give them these little containers and we put a vanilla sachet in every single one of them so that when they put their pills in there, it's masking any smell that might be associated with the minerals. They can be strong smelling but we also address that through the vanilla sachet. So we've really worked hard on maintaining that blind over the last, you know, two decades that we've been running these studies.

Dr Rupy: Amazing. Yeah so we've got data to show that people really struggle to guess what they what condition they're in.

Dr Rupy: Okay so that's also remarkable.

Dr Rupy: Yeah which is yeah, which is great. Um, so let's talk about the the hypothesis behind the multivitamins first. What multivitamins or micro you call them multi-nutrients, right? So what maybe we can distinguish between the two and why you use different terminology and what's the thinking behind supplementing with these specific nutrients and how they interplay with the body.

Julia: Yeah. So again, I I guess maybe my fourth caveat is that I'm a psychologist and not a manufacturer of supplements and so I study the idea and in order to study this idea, you need a supplement. And so I've always fallen back to those Canadian families um, not because their supplement is particularly, is is necessarily different from something else, but because I have studied other supplements and I find that those ones have always been better. And I think it's got something to do with that dose that they've been using um is relatively rare compared to what you'd buy in a supermarket. So the dose is much much higher and and the breadth is greater. So it's vitamin your your essential vitamins and minerals. So there's about 30 essential vitamins and minerals. So that's your B vitamins, that's your vitamin C, your D, your E. Um that would be your minerals, the full range, not just a few select minerals that people like because I bet you have your favorites like you might have magnesium magnesium yeah you might have zinc and you have a few favorites. And I suspect you have maybe a few favorites might some people quite like the B complex. So they might like a bit of vitamin D, but everyone would benefit from some vitamin D. So but I don't know if they when they teach that to you, do they tell you that when it goes around the Krebs cycle and then you eventually make ATP which is your energy molecule, did they teach you that every single one of those chemical reactions is dependent on vitamins and minerals?

Dr Rupy: So you're reading my mind. I've I've chatted with people not like you, Rupy, before but I kind of am familiar with that. And and they and we do we but it's I'm not I don't want you to feel blamed or anything for that perspective because I had the same perspective. I remember seeing Bonnie present her data for the first time and I'm thinking which nutrient is making the difference. Which one? And I absolutely honed in on that was like because I have been trained like you to think of a single molecule as being the way to change anything. So if you think about Prozac or you think about Ritalin, that's a single molecule that has such a big effect. So you're looking at this full array of your magnesium and your zinc and your copper and your molybdenum and your iodine, you know, the full range and you're looking at it going, which is it? which is it? And you're saying I'm thinking, I've read about ADHD and zinc. Is it the zinc? Or I've read about vitamin D and depression. Is it the D? Is it the D that's in there? Yeah. And so I want to challenge your audience to think that's the wrong way to think about it. because when you think like that, then you're assuming that you can change a complex psychiatric disorder with one single nutrient. And you evolved to need the full array of nutrients because as soon as you end up with a deficiency we and one of them, we can get disease. I think one of the reasons why we still fall back on this single nutrient fallacy is that there are a few um diseases that are cured with one nutrient. And so we know historically vitamin C for scurvy for example. Um, you'd have vitamin D and rickets. We have these very specific examples where just changing one nutrient has a huge impact on disease. But there aren't a lot of those examples. So more so it would be a broad spectrum. So if you think about the um, the making of serotonin, can I write this, can I do a diagram for you?

Dr Rupy: Yeah, you can do a diagram. Yeah, go for it. Here you go.

Dr Rupy: Oh you ran out of paper.

Dr Rupy: I ran out of paper but yeah, you could use that. You can write it.

Julia: All right. So if you just think about um, and this is going to be a terrible, you know, thing, but I can also give you a slide for this. So if you think about um, you know, chemical A Uh huh and chemical A is going to be your tryptophan which you get out of your diet.

Dr Rupy: So you're drawing a little box with tryptophan, just for the listeners, and that's pointing to another box that shows serotonin. Yeah.

Julia: So this is your this is a simple way of thinking about metabolic reactions. And it needs an enzyme which we make, but it also needs co-factors. And when you start to delve into those co-factors, they're always minerals and vitamins. And so that could be for one particular reaction, it might be just a couple, it might be B6 and zinc. But when you realize that that then gets broken down and that gets broken down and so there's another reaction here and you need your your co-factors here and your enzyme and then the same thing here and then you you then look at the big picture of all the chemical reactions that are happening, it's not long before you kind of go, oh my God, it's so dependent on so many different vitamins and minerals. So if you just supplement with one nutrient, you will just you're just going to clog up the system. It's going to it's if it doesn't have the other nutrients available, then you're going to end up limiting, having a limiting factor.

Dr Rupy: Totally.

Dr Rupy: So. I mean I totally understand that that argument. And you know, so just for the listeners, so you've got this one box going to another box and there's, you know, a couple of co-factors, so zinc or B vitamins, whatever that might be, but your point is it's not just those two boxes. There are hundreds of other boxes going on all requiring different nutrients to optimize the entire picture rather than just one pathway because if you just optimize one pathway, it's just one pathway. You haven't looked at the totality of it.

Julia: Exactly. So so now that you think about it that way, then you start to realize that this idea that we're going to find that magic nutrient is a fantasy. doesn't make any sense. It doesn't make any sense when we think about the biology. Yeah. And if you then start to think about other things that are going on, like if you think about the Krebs cycle, and I know that's something that apparently you learn in your first year. And there's something about how they forget it. But I I don't know if they when they teach that to you.

Dr Rupy: I don't I don't specifically remember the co-factors responsible for them. But to be fair, I wasn't paying that much attention in my first year of medical school. So I wouldn't I wouldn't be able to tell you.

Dr Rupy: No, no I don't think we would have. I mean I think the conversation around vitamins and minerals in the medical sphere, who, for the listeners in context, we don't get uh any nutrition training, nothing of practical knowledge. Um, ranges from 0 to 20 hours across a five to six year degree in the UK. Um, I'm sure it's very similar in Europe and certain parts of America although that is changing. Um so I would very much doubt that we would recognize vitamins in the way you've just set out with the diagram.

Julia: Exactly. So so if you think about the Krebs cycle, we know then it's dependent on the availability of vitamins and minerals. If you look at the methylation cycle, which is the creation of a carbon with three hydrogens, your CH3 molecule, the methyl group. methyl group is really important for epigenetic effects. So having an impact on turning your genes up or down, expression or not being expressed is dependent on the availability of these methyl groups. Well, that methylation cycle is dependent on having nutrients and not just one nutrient, there's some B vitamins that are really important, but there are other minerals that are important too. So the the the idea is that our metabolic system and metabolic activation is is dependent on full availability of all nutrients. Now our ancestors were getting that but we're not.

Dr Rupy: Why were our ancestors getting it and we're not?

Julia: Well because they were eating real whole foods and that's where you get them from. So the way to get your minerals is that you will get those out of the minerals are mostly in your in the soil and so we have to care about the depletion of minerals in soil but minerals are coming out of the soil, they get taken up by the plants and then you the they plants use those minerals to make vitamins. Um, and you either eat the plant or you eat an animal that ate the plant in order to be able to get access to those nutrients. We don't make them. A few of them we do, our microbiome make a few B vitamins but we don't make minerals. And so and and we've evolved, in fact vitamin C is one we've evolved to no longer make because you can get it out of your food. Well, I mean that's only if you're eating citrus, right? If you're eating a lot of fruit or things that are contain your vitamin C. But we evolved to not do it because that requires energy to make it. So aren't we clever to depend on our food environment to get access to these essential nutrients that are required for metabolic reaction. But you suddenly change that food environment and you take you reduce our consumption of your vitamins and minerals, that in itself can help us understand the development of disease and the onset and the the increasing rate of people who are challenged by our challenge by these mental health disorders, they don't have access to these nutrients that we depend on for the fight-flight response. So, you know, thinking chemical A to chemical B. Well, what do you need for fight-flight response? You need adrenaline, right? Same thing. So the fight-flight response and being stressed is entirely dependent on the availability of nutrients. So if you're always under stress, that's going to get it first because we evolved to always give it to the fight-flight response first at the expense of everything else. Your sleep, your ability to regulate your mood, do you end up being irritable when you're stressed? Do you end up being moody, difficult to manage those emotions? I think a lot of your listeners will that'll appeal to them.

Dr Rupy: Yeah I'm living it as well.

Julia: So and that's going back to that that resilience. So if your tank is empty and then you're stressed and you've got these things that our environmental stressors, not the tiger anymore, but those difficults and the challenges of our daily living, those nutrients get depleted. There is nothing left. And so if you're not constantly repleting that with good food, no wonder we struggle. And what do we reach for when we're stressed? We certainly don't go for broccoli. we don't reach for the broccoli because we evolved to reach for sugar when you're stressed. You need energy to run away from the tiger. So then we reach for those really carbohydrate rich types of foods that are going to give us glucose and so we're just doing it completely wrong.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, yeah.

Dr Rupy: So to summarize the the argument here around multi-nutrients, so you have your vitamins and minerals, they're all used in co-factors. They are used in turn in varying degrees in various points in your Krebs cycle and other cycles of which there are many to create hormones, uh, neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, um, other elements as well, other reactions in the body. Absolutely. Um, that we can go into a little bit later if you if you like. And so in a food environment where those are depleted, you can sort of imagine the cascade of effects that happen later on that lead to imbalances in people's mood and affect. And just to heighten or underline a point that you just made there, if you put someone in a nutrient-deprived scenario and you stress them with some of the exogenous stressors that we talked about, your alarm clock going off, your emails at work, the stressful journey you have into your I mean I was just in traffic the whole time, so my cortisol levels were probably quite quite high today. Um, those are what get prioritized as a result of how we've evolved. And that's where you lose the availability of the co-factors for other things that are just important.

Julia: Just important. You got it. Exactly. Yeah, beautifully summarized. So then we start to understand that we need more nutrients. And that's why I'd still say try and get it out of your food, but there's a lot of reasons why we don't get it out of our food. I mean the first most obvious one is that we're eating ultra-processed products. And so when when when those foods are made, they get stripped of a lot of the nutrients. And so I've done I often I I came up with this graph that I'll show, I started showing it to like 10-year-olds because I wanted to really explain the difference between your Spam, which is spiced ham. I don't do you have it here? They have it in New Zealand.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, there is spam here. It comes from a tin.

Julia: Yeah, the tin or you've got your french fries or you've got your um, which is not necessarily I hate to demonize french fries entirely because they are not always terrible. Um, but you've got your white bread, um you've got these foods that we consume, your your soft drinks, no nutrients, Coke Zero. there's no vitamins and minerals in those unless, you know, there are some soft drinks where they're starting to like fortify them or add them in, but they're always adding them in at really low levels. When you look at the amount relative to your recommended dietary allowance which in itself is not my favorite metric, but I'm happy to go into that. But even then it's really low. So it might say it's fortified with these nutrients, but the doses are so low that they're not adequate for really supporting us to be optimizing our brain health. They might be enough to prevent you from getting scurvy, but they're not necessarily what your brain needs. I mean just, you know, just thinking about the RDA, which you'll see on either that or your DV or it'll say it'll say RDA, it'll say something like that on the back of packages. That's a a that was that concept was developed post World War II to ensure that our troops would fight and be able to be ready and prepared um for combat, not for your brain. So it's about your heart or your muscles, but it wasn't about optimizing your brain. And when you realize that the brain punches above its weight, uh in that it's 2% body weight but it consumes 20 to 40% of the nutrients that you eat, you realize that the RDA concept, I mean, we should scrap it and start again.

Dr Rupy: Really? Yeah.

Julia: Oh yeah. I mean, we people start to get fixated on these metrics. And I've come across this a lot in the in again the research because we're giving the nutrients above the RDA. Yeah. Sometimes quite much quite higher than RDA. And so initially when I first started to do this, like, oh my god, we're going to kill people, we're going to poison them. You can't possibly go above the RDA. And then I realized that the kiwi fruit, which is, you know, one of the New Zealand um, you know, fruit that we export and make lots of money out of. The vitamin C goes way above RDA.

Dr Rupy: Oh really?

Julia: Oh yeah it does. And I and we're not poisoning the rest of the world. So we must be okay. So if you were to even.

Dr Rupy: But is that because that's a water-soluble vitamin versus.

Julia: No not sorry yeah that's not necessarily the best example because I knew you'd say that. So if we even look at something like if you were to um consume five selenium nuts, you'd go over the RDA and selenium. You don't want to go way go way over because we appreciate that there you can go toxic. But you're not going to kill yourself by having six Brazil nuts but you're going over the RDA and selenium. So um, that concept is useful for prevention of scurvy, for prevention of rickets. It's a useful concept, but it's not a number that we should be relying on for our brain's needs. And so we're working in a sort of a I think I've got a diagram for this.

Dr Rupy: Yeah I was going to ask you in terms of the RDIs for the multi-nutrients that you're using in clinical research, what kind of numbers are we talking about in terms of those above.

Julia: Exactly. No I'll show you. I think that's next to show you. So here is your your how much. So here's your RDA and your UL. So your UL is your upper limit. But it's if you consume something at the UL, that is not toxic. So that's what people sort sort of think I should I cannot go, you know, oftentimes people will say I can't go over RDA. But I've just explained that even if you had a kiwi fruit, you'd be going over RDA vitamin C or some Brazil nuts or even if you had a cup of lentils, you'd be going way over on some of those nutrients. And again, we don't have people killing over and dying from having lentil soup. So when we look at real whole foods, you're often going over the RDA. But um, when you eat ultra-processed products, you're sitting around here, you're down at about 25% often times.

Dr Rupy: So just for the listener, so we have a diagram. It's a very simple diagram with intake along the Y-axis and you have uh, RDA which is sort of at the, you know, a couple of units across. And then you've got the upper limit, which is still a safe limit of intake, but it's almost like two, three times the RDA, maybe a bit more. And then above that, there's the uncertainty factor and then, you know, we don't know whether there's toxicity beyond that.

Julia: Exactly. No you do get eventually you might get toxic. But what's important to But there's a lot, I guess your point is there's a big, big leeway between those.

Julia: Exactly. So most of the nutrients that we're giving is within that in this what we call the what we think is the therapeutic range. So the under here that'll stop you from getting deficient, a deficiency like as I said scurvy or something like that, but that's not optimizing your brain health. We think that's where you're going to get the best hit. Um now we sometimes some of the nutrients go over the UL and that's because the UL, all the ULs are are determined based on taking that single nutrient by itself. So for example, if you were to take zinc by itself, you would eventually cause could cause a copper deficiency.

Dr Rupy: Okay. Because zinc. explain that first.

Julia: Well because they both they both work together and that when you if you end up with just only taking one, then you end up with a deficiency in the other because of the metabolic reactions.

Dr Rupy: Okay, gotcha. So because of the metabolic reactions. So they are they like antagonistic pairs? Is that.

Julia: I don't think they're antagonistic but I think they might work on the similar similar pathways and so you need both of them being present. But if you take zinc with copper, then you end up with no problem. So then you can take zinc above the UL and it's not going to be toxic. So the there's other combinations where you end up with that. Magnesium, if you go over the the the UL for magnesium, you increase your likelihood of having diarrhea. But if you take it in combination with those other minerals, we tend to mitigate reduce that likelihood of that particular side effect. It still does happen in the first few weeks. We have about 20% of people will report changes in bowel movements. And that tends to get better as their body gets used to the nutrients. So it's a time-limited problem.

Dr Rupy: So the ULs are useful but only to a certain extent um and when you start to combine them with other nutrients, you realize that they are of limited more limited use. So we need to care about toxicity. We don't want to kill our patients and our participants in our research. So we are very mindful of making sure that we don't harm them. And we look for that. We're always looking for harm and we're always looking for negative side effects because obviously I want to know and the public want to know if there's harm. And you'll often hear these headlines, the latest one was B6 toxicity, and that when reverberated around the world and ended up in my inbox multiple times. And it was it's interesting because it was about B6 toxicity causing irreversible neuropathy in I think it was just a few people in Australia. I'm not sure. I mean they uh neuropathy can happen with B6 particularly if you take it by itself. It tends to be reversible, so I'm confused about why it was irreversible. But neuropathy, as a medical person, you would know that neuropathy can happen with medications as well. Yeah, yeah. And one of the things that I want to get into is the interaction between the nutrients and medications because that's a challenge. And if you add in nutrients at these doses, you can potentiate medications.

Dr Rupy: When you say potentiate.

Julia: Meaning that the side effects increase and it becomes a stronger experience of having that medication.

Dr Rupy: So the the dose of medication may need to be reduced as a consequence.

Julia: You got it. Yes, which is I think a tricky thing for prescribers to recognize because when people start getting worse, they tend to increase the dose of the medication rather than reduce it. So it's kind of counterintuitive. But in fact, you are absolutely right, you need to start reducing the dose down as the micronutrients are added in. A better scenario is to do the nutrients with people who aren't medicated. But I appreciate that given so many people are medicated, then you need to learn how to cross prescribe.

Dr Rupy: Gotcha. Um, I want to pause there, just before we go too deep in the weeds around nutrient interactions and everything. Um, so I hopefully the listener and I understand the impact of multi-nutrients on the functioning of a number of different enzymes in your body, how that impacts hormones, neurotransmitters, etc. Um, the potential use of these in a poor diet environment, so you're actually replenishing nutrients that you're not getting from your food. But then the perplexing question is within other data or other literature, the use of multivitamins hasn't shown much. you know, there doesn't appear to be an impact on reduction of cancer, reduction of cardiovascular disease. Um what's your sort of take on those studies?

Julia: Yeah, um and that's often what you hear about. Yeah. I guess I my take would be first of all, my focus is on mental health problems only and challenges only. And so my expertise in those other areas is more limited. I do um but when I have looked at them, they'll often have only taken a select few nutrients. So they'll have given a maybe vitamin, I think some of those studies were like vitamin E and A and like ACE and something.

Dr Rupy: Yeah like ACE and something yeah.

Julia: Something yeah. So so they are only looking at the three. So if we think about metabolic reaction from the perspective of cardiovascular health, I assume you need the broad spectrum again. Why would you just focus in on a few? I mean, I understand the mindset that's led to that kind of research. But I wonder if I wonder if it's the wrong approach. But I don't know because it's not my area of research. So I think that happens. Their doses are way low. When you look at the doses, they're down here.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, I was going to say the doses that I've seen are nowhere near they're usually at the RDA level. They're not at the upper level.

Julia: Exactly. So I do wonder if it's got something to do with that dose effect. Um but the other interesting thing that happens in the mental health space and so I'll often talk about this within the context of of the number of studies that have been shown to benefit mental health problems. People will study uh, the impact of vitamins or minerals or a combination on mood, but they'll recruit non-clinical samples.

Dr Rupy: Non what's that?

Julia: Non-clinical samples. People who don't have a mood disorder.

Dr Rupy: Oh wow.

Julia: I know. I know and it's it's been fascinating to go why in the world would you study mood in people who don't have mood challenges. So then, of course, you're going to end up with no one necessarily getting better. So what I've done here is that I've just collated it's pretty much up to date. This is looking at studies that have taken a broad spectrum, not even the same level that I've been taking which is, you know, over your 30 essential, around 30 plus some amino acids and other important nutrients. Some of these are these are just B complexes. And what I've done is I've said positive or negative RCTs. And negative is um where the placebo is as good as the micronutrients and positive means that micronutrients outperform the placebo. So I've looked at I've I've delved through the literature, but I've also included in here studies that have been done on people who don't have anything wrong with them, so non-clinical samples. But also I've included studies in here where they've they've only used up to the RDA. So I haven't I haven't tried to cherry-pick the ones, I haven't tried not to cherry-pick just what I've done. or or people who have really been more true to this concept of going above the RDA. So I've been inclusive. And when we do that, we get about 78% of the studies and there's been I've been able to count 63 and these are global with respect to mental health problems, then you end up with 78% of the studies being positive.

Dr Rupy: Huh. So out of the just to summarize for the listeners, so out of the studies that are looking at multivitamins, um rather than isolate there's some just B complex.

Julia: They're some that are B complex.

Dr Rupy: Okay, but the majority of them multivitamins across a spectrum of different conditions, aggression, you've got autism there, addiction, um stress, ADHD. Yeah I've tried to be broad.

Dr Rupy: Yeah so broadly speaking and with all the caveats that you just mentioned in terms of under-dosing and, you know, these aren't just your studies using the multi-nutrients at the doses that you've just described, there does appear to be a positive effect in 78% of them.

Julia: Correct. Yes. Wow. Yeah. So that's that's not bad. And I as far as I know. Yeah points in the direction of something going on.

Julia: It does suggest there's something going on. And that that I think does I don't think there are any studies out there that haven't been published. So if you look back 20 years, we understood that a lot of studies on antidepressants that were negative weren't being published. So I think I know the field well enough to know who's doing these studies and there aren't a lot of us unfortunately. So I think I know them and I think that the studies have eventually been published. Understand that in this space, it's really hard to publish studies. There is a lot of opposition, it's hard to get through the gatekeeper. It is getting better. So um, for example, the last study that was done on ADHD, it wasn't mine. It was called the MADDY study. It's not in the book because it came out after the book. Um, but it was um a group of American researchers and Canadian and they got it into um the a JACAP, which is the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, which is the top child psychiatry journal. So we are starting to get some momentum. my first RCT after huge amount of effort and rejections and appeal to the editor, I got it into the the British um journal of psychiatry. So which isn't bad. But that was hard work and it was after I think a year. Nutri-Mum, which is I know we're hopefully we're going to have time to get to that was the hardest study to publish in my career and I don't know why because it was such exciting data and so um inspiring for moms who um are pregnant or who want to get pregnant. But that one took us two years to publish. Gosh. And and it just it's it's you have to wonder why did it take us so long and it's not and we're doing RCTs, it's not like we're doing some kind of other observational studies or whatever. These do tell us a bit more about causality. So so I just want you to know that I'm I I as far as I know there aren't any negative studies out there that haven't been published that would would change this ratio. So it really has tried to do my best.

Dr Rupy: Yeah no clearly, clearly and the passion comes through as well of course. Um, I think it's great to to to understand like your initial perspective on multi-nutrients as a result of your conventional training and how you've almost had to convince yourself that there's something going on here. Yeah. Um, and just as a side like, you know, how might one understand or what kind of symptoms should people be looking for that speak to them being potentially deficient in nutrients. Are there certain things that we look out for?

Julia: So, um, that is a really good question that comes up a lot and I think about a lot and I've thought about from the perspective of our data. So you would think that there's a deficiency that's probably going on. But not the kind of deficiency that you might be thinking of because I think what you might be thinking of, um but correct me if I'm wrong, is a deficiency that you go and get a blood test and you go and find out that your vitamin D is low and then you correct that with additional vitamin D. Um I think that has some usefulness but I'm not convinced a lot when it comes to this approach. And I'll try to explain and it's based on data. It's not I would have thought the same way as you, we just need to find out who's deficient, find out what they're deficient in, and then we will correct those few things that are wrong and then they'll be fine. But when you think about the biology again, you realize that that's probably going to create other deficiencies, kind of like the way I talked about zinc and copper. You can end up with deficiencies being created when you just give a few. But it's making the assumption that the people you are being compared to when you do a lab test have got the same issues as you and demands on your life. But if you're somebody who's going through a life stage, you're a teenager, your brain is going under reconstruction. I've just had two teenagers, they're now in their early 20s. Um but they definitely, it's an interesting stage of life and you have that to look forward to, I understand. And I love the concept of thinking about it as brain going undergoing reconstruction because that's incredibly metabolically active time. And so no wonder in fact their nutritional needs are higher than your average individual. Or if you're pregnant, of course I think that's one that people will recognize and appreciate. Or if you're really stressed, if you're someone who has a lot going on, your nutritional needs are higher as I explained, you're going to need those nutrients to support the fight-flight response. So there's a lot of factors that can influence our nutritional needs that aren't going to be captured by a blood test. So I might look normal, but I need more. So I might be deficient relative to my own nutrient needs rather than the average. So and I only come to this conclusion because what we've done is that we've had the opportunity of doing nutrient levels before people start the the treatment. And then we measure them again. So we measure them eight weeks later or 12 weeks later. I appreciate that's not a a long-term thing, but that's hard that's in itself hard to do.

Dr Rupy: And what kind of nutrients are you looking at?

Julia: So so we can't measure all your nutrients, right? And so then you know that as soon as you realize that, you realize that we'll never, you would never supplement or think to supplement with I always give the example of molybdenum unless you know, do you test for that? No. So our standard things that we test for would be zinc, you might do copper, you might do vitamin D, you might do B12. Uh huh. what else might you do?

Dr Rupy: iron, yeah would do an iron. level yeah. we might do an hsCRP but that's more broad spectrum inflammation yeah.

Julia: So what other nutrients might you do?

Dr Rupy: Omega-3? Yeah and we can talk about omega-3s we haven't even talked about that. that's important too. Yeah I have so I I I'm going to have so.

Julia: So you don't actually do the full array. You're not doing the full spectrum. So then you're so it's like the street light effect, which is that your keys are lost over there but we're looking for them over here because this is where the light is. So that it does I've starting to be less enthusiastic of that approach. And but again it's data driven. So we did the nutrient levels, the ones that would be standard for if you went to see your GP. And most people are actually normal. There's about a third are low in vitamin D, but that's probably pretty standard. So most of them are normal in the nutrients that we tested. Yeah. And that didn't predict when we select out those who are deficient, if it was based on deficiency as being the driver of benefit, then those people should do better. but they don't.

Dr Rupy: They don't?

Julia: No.

Dr Rupy: So that's counter-intuitive.

Julia: It is counter-intuitive and it's forced me to have to think about it in this different way because otherwise I would have thought about it from your standard deficiency model. Yeah. But it's made me think, okay, there's some there must be something other things that are going on and that we are looking at this very simplistically. I don't know how we should look at it and I'd love to kind of figure out is there a test that we could do to predict who's going to benefit? But at the moment, we've looked everywhere. We have scoured our data. We don't we probably don't have a big enough sample. There are probably, other challenges. The MADDY study, which is the one done in the states, they found the same thing. So that finding has been replicated which is that we can't find any nutrients that predict response and also that it doesn't even mediate response, which just means that um, when I looked at when we were looking at blood levels, some blood levels go up, not all of them, that's important to know as well is that some blood levels, some things are kept really closely in homeostasis in your blood. So unless you're about to die, I think some of them are just pretty much within a really tight range. Whereas something like B12 will skyrocket. It will skyrocket. Up but it'll skyrocket in people who are not pregnant, but what we've learned is that women who are pregnant, their B12 does not go up even though we are giving them an enormous amount of B12.

Dr Rupy: Really?

Julia: Yeah, they do not, they go up a little bit but nothing like what we were seeing in our non-pregnant populations. So that fetus needs a lot. Something's going on. And so we were not seeing the the blood levels rising the way we were experiencing in non-pregnant populations. So.

Dr Rupy: So but it wasn't pre it didn't predict who.

Julia: it didn't predict it. So again I I would look at these levels going up and I'd see some people their B12 wouldn't change at all even though we're giving them a lot of B12. I think, okay, that's going to tell me that person is not responding. It didn't work. So it leaves us with more questions than answers.

Dr Rupy: Yeah, so it speaks to the inability or the flaw in the investigations that we currently have at the moment rather than um the fact that the multi-nutrients aren't changing their biology. And you'd assume that it would be, the nutrients would change what you see. But I think it's the and to your point, I think it's because of homeostasis. So if you think about, I don't know, your blood pH level, potassium, calcium, these are things that are highly, highly regulated because they're so required for, you know, very, very important processes in the body like muscle contraction, in the form of calcium for example. Um and even, you know, making making sure your acid-base balance is normal. Um so I think it speaks to the the investigation flaws.

Julia: I think so. I think we just haven't hit it. So I always talk about personalized medicine. And I love the idea that you could go and get tested and get everything correct. But I always say to people who who take that approach, I say, well, you need to prove that that's better than just giving a broad spectrum. And I need to see the study that randomizes people to the personalized approach, which is let's find out what's wrong with you and deficient and and give you those, which is what some people I understand will do versus let's just give you everything that your body needs and it'll get rid of the rest. And, you know, we need to be mindful of not causing any risk and I'm happy to talk about that. Um and if if the personalized medicine ones do better than the broad spectrum, then I will embrace it and I will be driven by data and I will give up on this approach. I haven't found anyone who wants to do that study. And I don't have the enough of sufficient expertise and been able to do that, so we haven't done it. So until that happens, I guess I I would be cautious around the need for that. I think there's a need for it, of course, to identify a deficiency, but what I my point being that even people who weren't deficient benefited from the multi-nutrient approach, then that suggests to me that you don't have to have your blood tested to give it a go. because you may you may benefit from more.

Dr Rupy: From more. Okay. I want to step aside from multi-nutrients just for a moment. I want to go I want to get back to them in a second as we talk about specifics with um, mental health conditions and we can go deep into into some of them if you if you like and we'll go into the Nutri-Mum study as well. Um, you wrote a chapter in the book which I found fascinating called not your grandmother's peach. And it speaks to everything from how our environment and our soil has changed, which has led to deficiencies for want of a better word in our food.

Julia: Exactly. What's going on there?